Lily Briscoe, who isn't Alpine climber Lily Bristow

Is Virginia Woolf’s ‘To the Lighthouse’ a book about mountains? Well yes, sort of ….

Lily Bristow, top mountaineer of the 1880s, lives on, oddly, in Virginia Woolf’s novel of 1927; a book set entirely at the seaside. Where she reappears, sort of, as a character called Lily Briscoe, a painter and friend of the Ramsay family.

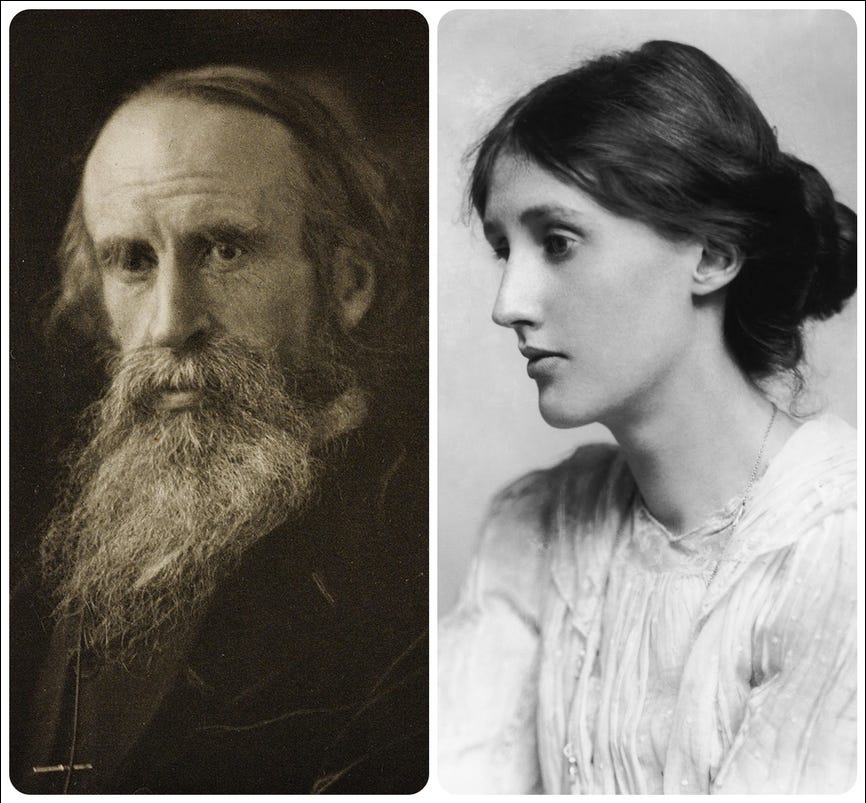

Because I’m interested in Lily Bristow, I was reading To the Lighthouse. And about three chapters in, I started to wonder: this Mr Ramsay, elderly philosophical gent, could he possibly be a portrait of the famous mountaineer Leslie Stephen? Leslie Stephen, author of the classic The Playground of Europe and ascender of the Schreckhorn and the Zinal Rothorn, who also happened to be Virginia Woolf’s dad?

I asked the Internet. And the Internet said Honestly, Ronald of course Mr Ramsay is a portrait of Leslie Stephen. Everybody knows that.1

Yes, To the Lighthouse is a book about Woolf’s mother Julia and her dad Leslie Stephen. The same Leslie Stephen who had once been the leading mountaineer of his time; those, indeed, had been his ‘best years’ (according to VW’s own account of him in ‘My Father Leslie Stephen’). [All references and links in footnote2 below.]

Mr Ramsay in the novel, like Leslie Stephen in the years after Virginia Woolf was born, is a Victorian man of letters and philosopher. But yes, there is still, in the misty background of the novel, a presence of mountains.

There is, for instance, the very minor character of Marie the Swiss housemaid. Her only role in the book is to be heard crying in her room, homesick for the hills of Canton Graubunden: “The mountains are so beautiful.” What’s she for, then? Leslie Stephen, for the rest of his life, was nostalgic for his mountain-climbing time: on the streets of London he would wear the old coat with the rope-marks from Mont Blanc. I see Marie as a minor avatar representing this side of Leslie Stephen, where making Mr Ramsay himself a mountaineer would distort the story.

But then, at one crucial (and even comical) moment, Mr R does head into the hills… What he’s actually aiming to climb up and conquer is Epistemology, the philosophy of the Nature of our so-called Reality. And his anxiety is over his own accomplishments and legacy; as he assaults the heights of Metaphysics in the manner of a mountaineer. Will he reach the top? And will his life work be remembered?

Feelings that would not have disgraced a leader who, now that the snow has begun to fall and the mountain top is covered in mist, knows that he must lay himself down and die before morning comes, stole upon him, paling the colour of his eyes, giving him, even in the two minutes of his turn on the terrace, the bleached look of withered old age. Yet he would not die lying down; he would find some crag of rock, and there, his eyes fixed on the storm, trying to the end to pierce the darkness, he would die standing.

Poor Mr Ramsay! In the absence of Mrs Ramsay (no first name is ever given for either of them), he looks to Lily Briscoe for comfort and a boost to his frayed ego. Which Lily is in no way able to provide – except that she does, by a casual remark about his boots. Ah yes! Like any mountaineer, Mr Ramsay is immensely gratified by the good qualities of his boots… “There was only one man in England who could make boots like that.”

Another important moment: Mrs Ramsay is comforting her daughter Cam with a bedtime story. A story about the consolations of mountain scenery. “A beautiful mountain such as she had seen abroad, with valleys and flowers and bells ringing and birds singing and little goats and antelopes … ”

And then there’s James: the sulky son, furious after his father determines that the weather will be wrong for the boat trip to the lighthouse; and then, 10 years later, furious again that Mr R has decided to sail to the lighthouse after all, and obliging his now teenage children to tag along. But, in the moving boat, his father quietly reading his book as James is at the tiller steering; James visualises the two of them, alone above the world on a high mountain:

Yes, thought James, while the boat slapped and dawdled there in the hot sun; there was a waste of snow and rock very lonely and austere; and there he had come to feel, quite often lately, when his father said something or did something which surprised the others, there were two pairs of footprints only; his own and his father’s. They alone knew each other.

For many years, Woolf was wanting to write something about a mountain. At the very end of her life – the last story she ever wrote, in fact – VW wrote about the Matterhorn: in a piece that echoed and took further her father’s own description of sunset on Mont Blanc in The Playground of Europe.

[Lily Briscoe on the terrace, preparing to paint] She seemed like an unborn soul, a soul reft of body, hesitating on some windy pinnacle and exposed without protection to all the blasts of doubt.

So what about Lily, whether Briscoe (in the book) or Bristow (in real life)? It’s unlikely that Woolf and Bristow ever met: Bristow was 18 years older, and had long given up climbing by the time Woolf was grown up. Though, maybe it’s just coincidence: but Lily Bristow was also a painter; though did VW even know that while creating her character Lily Briscoe?

With her little Chinese eyes and her puckered-up face, she would never marry; one could not take her painting very seriously; she was an independent little creature, and Mrs Ramsay liked her for it.

Briscoe is an important minor character in the book. Not just an insightful observer of Mr and Mrs Ramsay, though she is that, but also a counterpart to Mrs Ramsay herself. Mrs R is the traditional Edwardian wife and mother; beautiful, caring, living for her family and her effect on others. Lily is plain-looking, with ‘Chinese eyes’; uninterested in marriage or children; justifying herself through her work as a painter against the disapproval of the odious Mr Tansley: “women can’t paint”. And indeed, Lily is the main avatar of Woolf herself within the story – not just in her career aims as an independent woman, but in her painterly eye, a way of looking at the world that’s also the way Virginia Woolf is presenting the book itself.

One wanted, she thought, dipping her brush deliberately, to be on a level with ordinary experience, to feel simply that’s a chair, that’s a table, and yet at the same time, It’s a miracle, it’s an ecstasy.

And when VW was considering the woman she wanted for her story: considering the woman she wanted to be, herself, in her own life. What more natural than she should recall the stories of adventure in the mountains: “the stories he [Leslie Stephen] told to amuse his children of adventures in the Alps — but accidents only happened, he would explain, if you were so foolish as to disobey your guides”. And bring back the name of that most impressive of lady adventurers, Miss Lily Bristow.

Bizarrely I had the same experience again – when reading Thomas Hardy’s ‘A Pair of Blue Eyes’ for the sake of its exciting cliff-climbing episode and meet-up with a trilobite fossil. This time the Internet was slightly kindlier: no, Ronald, not everybody knows ‘Henry Knight’ is a portrait of Leslie Stephen. But yes, he is. Seems like Leslie Stephen made a big impression.

References:

My Father, Leslie Stephen: Virginia Woolf’s account of him including his nostalgia for the Alps

Virginia Woolf meets the Matterhorn: her late short story ‘The Symbol’

Leslie Stephen on Mont Blanc: my earlier Substack post

Virginia Woolf Reading Group: readthrough of ‘To the Lighthouse’ on Substack ‘Wolfish’

Lily Bristow, mountaineer: my last week’s post about the original Lily