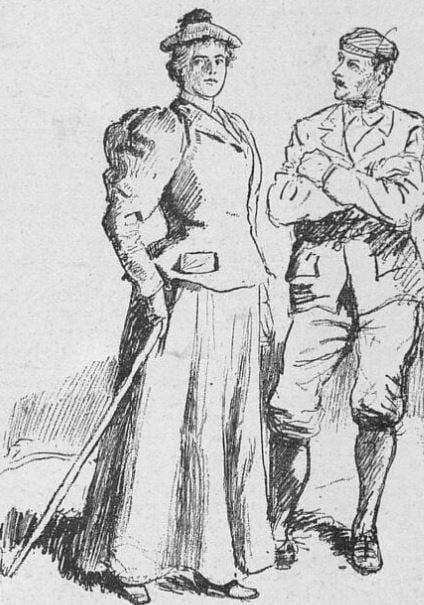

Lily Bristow, ace climber of the 1890s

Not just the top woman climber, but one of the top climbers full stop; and she took photos of it too. [1750 words, 7 mins

Mountaineering, as invented by 19th-century English gentlemen, was such a weird sport that, just sometimes, some of the normal social rules didn’t apply. Right from the start, the upper-middle-class barristers and academics were climbing alongside, and forming lifelong friendships with, peasant farmers from the Cantons of Switzerland. But of course, women were excluded from this butch and adventurous sport:

Strong prejudices are apt to be aroused the moment a woman attempts any more formidable sort of mountaineering… The masculine mind, however, is with rare exceptions, imbued with the idea that a woman is not a fit comrade for steep ice or precipitous rock… She should be satisfied with watching through a telescope some weedy and invertebrate masher being hauled up a steep peak by a couple of burly guides, or by listening to this same masher when, on his return, he lisps out with a sickening drawl the many perils he has encountered.

Mary Mummery, from ‘My Climbs in the Alps and Caucasus’

But not all the women were prepared to put up with it (and, indeed, not all of the men were quite so prejudiced). In a previous post I’ve celebrated some of the women who girded up their hopelessly impractical skirts in the early-century Alpine explorations. As the game developed from simple summit-bagging into finding new and technically difficult routes, two adventurous Ladies were up there at the forefront, climbing alongside the top mountaineer of the time, Albert Mummery.

Mary Mummery, Albert’s wife, shared in the first ascent of the Teufelsgrat or Devil’s Ridge on Switzerland's second highest mountain, the Täschhorn. But even more talented was her friend Lily Bristow.

A solicitor’s daughter from Clapham Common in south London, Bristow already had an unusual start for a woman at the co-educational Clapham School of Art. Women artists were almost as disapproved of as women climbers, exhibiting at the Royal Academy in a special little enclosure, and offered life drawing only of a model in a decorous state of partial drapery…

She moved on to the forward-looking Herkomer Art School in Bushey, where she shared lodgings with a fellow student and future suffragette called Edith Petherick – whose older sister was Mary Mummery. And so the adventurous art student becomes an adventurous mountaineer.

The big challenges of the 1890s were the Chamonix Aiguilles: near-vertical steeples and towers of granite spiking the sky immediately to north of Mont Blanc. In 1892, aged 28, Lily joined Mary and Fred Mummery for the crossing of the Aiguille des Grands Charmoz.

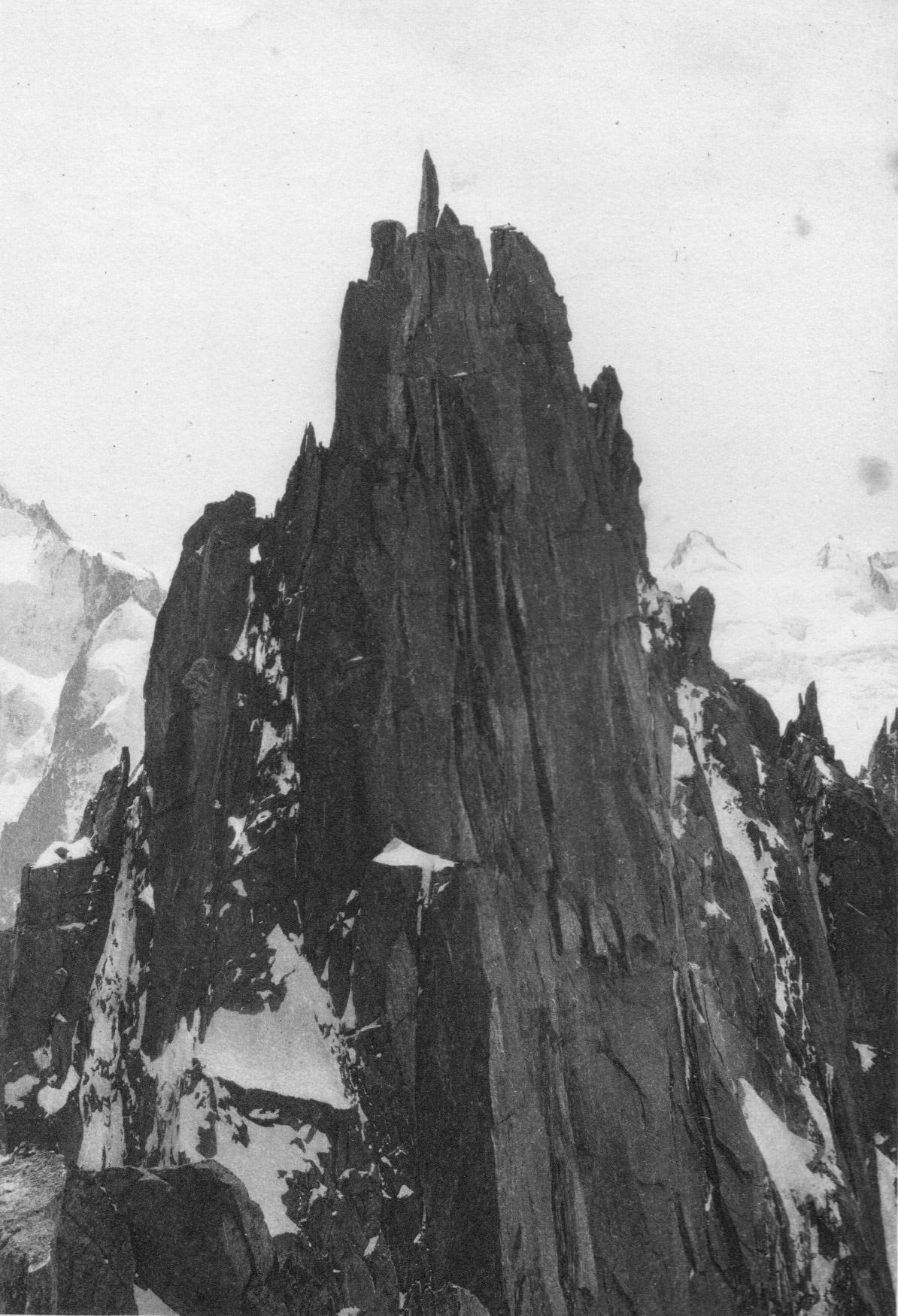

The Grépon

The following year (1893) she scandalised respectable climbers by sharing a mountain tent on the Nantillons Glacier with Mummery and his friend Geoffrey Hastings, before an early re-ascent of the Aiguille du Grépon – at that time considered the hardest climb in the Alps. “Three people in one tent 6ft x 4ft was a tightish fit” – Lily wrote in a lively letter to her family.1

Like everything else in the Alps, a night out is in itself a great pleasure … Few places can rival the narrow ledge of rock, with a precipice in front and an ice slope rising behind, where our tiny tent was pitched, and few setting suns have disclosed more gorgeous contrasts and tenderer harmonies than that which heralded the night of August 4, 1893.

AF Mummery, My Climbs in the Alps and Caucasus

They were joined in the morning by “three more gentlemen who’d preferred to toil up the moraine stones in the dark with the horrors of the folding lantern.” These were a Mr Brodie, with Norman Collie and WC Slingsby. (UK rock climbers will be aware of Collie’s Ledge in the Cuillin and Slingsby’s Chimney on Scafell. Collie’s own mountain autobiography mentions Mummery and Hastings but oddly leaves out Lily Bristow.)

Lily and Mummery lead off up the ice, step-cutting while the rest are enjoying a second round of breakfast. Mummery is hauling Lily’s very cumbersome half-plate camera and its tripod.

I have often felt, on the climbs, that if I had sufficient knowledge and pluck I could have done it by myself, but this climb was something totally different. It was more difficult than I could ever imagine—a succession of problems, each one of which was a ripping good climb in itself,” Lily writes. “Fred (Mummery) is magnificent, I never had the least squirm about him even when he was in the most hideous places, where the least slip would have been certain death, and there were very many such situations.

“The Grépon… is a real snorker” – Lily Bristow

Meanwhile, according to Mummery himself: “Miss Bristow promptly followed, scorning the proffered rope. The lady of the party, surrounded on three sides by nothing and blocked in front with the camera, made ready to seize the moment when an unfortunate climber should be in his least elegant attitude and transfix him for ever.

She took the photo of Mummery in the so-called ‘Mummery Crack’, using the massive camera, then “showed the representatives of the Alpine Club” – which of course did not admit women – “the way in which steep rocks should be climbed”.

Delayed by photography, and by rain on the descent, they inished by lantern light. Back at the glacier at 11pm, and all six now in the 6 x 4 tent. “The wind was that rampageous, that I can’t imagine how the fellows managed to hold the tent down at all.”

Rejoice with me, for I have done my peak! The biggest climb I have ever had or ever shall have, for there isn’t one to beat it in the Alps.

The Dru

The summer of 1893 will long be remembered as an extraordinarily favourable one for climbing. Week after week a clear sun was shining out of a cloudless sky, and the result was that more peaks were scaled than in any previous season since the gloriously fine year of the Queen's Jubilee.

(The Alpine Journal).

Queen Margharita of Italy was out on the mountains that year, enjoying a hut night on the Punta Gnifetti. Also out was one Winston Churchill making his only mountain climb on Monte Rosa while getting an attack of mountain sickness and a ‘badly flayed’ face. Meanwhile evil wizard Aleister Crowley was putting up a new route on the Napes Needle above Wasdale Head. And Lily is again sharing a tent with Slingsby and Mummery, before an attempt on the Petit Dru.

“Fred let me lead [she had an idea of the route, having previously watched a descending party] which I always enjoy, it is so much more exciting.” After breakfast on the col, “the climbing was pretty stiff, I must say, though not nearly so difficult as the Grépon, which is a real snorker… Fred’s exploit: taking a lady up the two most difficult peaks here, without guides, in the course of one week, with a new and very difficult route on the Aiguille du Plan2 in between, is really worthy of some applause.”

Rothorn from Zinal

For the Zinalrothorn, Mummery and Lily Bristow were up at 1.30am. But the hotel keepers hadn’t been able to believe they would be attempting the mountain, and there wasn’t any breakfast for them; so they didn’t get away until 2.45. This was really too late (today, the mountain is climbed from a hut 1200m above the village), and at 7am, after no more then the initial path in the dark, Mummery decided to turn back.

However, Lily “begged and prayed in my most artful manner”, and persuaded him to “go on a bit and see” – with the stipulation that they’d turn back at 10am if they hadn’t reached the col below the ridge; and if not then, then at 2pm, wherever they were on the mountain.

Whereupon Lily fiddled with their watches… They were indeed late at the col, but (whether or not Mummery was wise to Lily’s trickery) they went on up the fabulous narrow ridge, and reached the top at 1.35.3 They descended so fast that the rope knocked Lily’s hat and goggles off her head, and so “completely ruined my cherished complexion!” They got back to the village at 9pm. The hotel people continued to disbelieve in their ascent – after all they didn’t even have a guide: “Non Madame ce n’est pas possible!” Their navigation must have been off, they’d climbed some grassy hillock and not the real Rothorn.

On 24 August, she climbed the Italian ridge of the Matterhorn with Mummery, Collie and Hastings, followed by the first ever descent of the mountain’s more difficult Zmutt ridge. Completing in one season four of the hardest Alpine routes available in the 1890s.

Four years later, Albert Mummery died while attempting Nanga Parbat, one of the 8000m giants of the Himalayas. But Lily had already stopped climbing: after just those two high-achieving years on the mountains.

Why did she stop? It’s been suggested that Mary Mummery resented Lily’s tent-sharing with Fred – although there’s no actual evidence for that. Lily’s frank letters home suggest that her family was accepting of her strange pursuit. It may simply be that she couldn’t afford the travel; or wanted to devote herself to her artistic career. She exhibited at the Royal Academy in the late 1890s, and a fine art website describes her as a “remarkable painter of landscapes and genre scenes”.

Lily never married, and her later life became less and less adventurous, at least where conventional biography is concerned. Until 1925 she was looking after her ageing mother in Haselmere, in the Surrey Hills. In 1927 she may or may not have noticed her name being borrowed by Virginia Woolf for the independent-minded painter Lily Briscoe in To the Lighthouse.4 In 1928 she designed a banner for the Mothers Union, and took an active part in the affairs of the parish church. She died in 1935, aged 71.

Her obituary in the local paper didn’t even mention her Alpine ascents.

Lily Bristow’s letters home reprinted in the Alpine Journal 1942 .

The Aiguille du Plan is described in Mummery’s My Climbs in the Alps and Caucasus (1895), along with Lily’s day on the Grépon.

I’ve been there, and the picture from ‘The Playground of Europe’ is not in any way romanticised. It really is just like that.

Next week’s post will explore why the accomplished lady climber reappears in Virginia Woolf’s book set entirely at the seaside.

Wonderful- I never knew, top stuff. Thanks