Leslie Stephen climbs Mont Blanc

One of the inventors of Alpinism also happened to be Virginia Woolf's dad [1600 words 7mins

Leslie Stephen was knighted for his services as a Victorian man of letters, in particular as the first editor of the Dictionary of National Biography. He edited and consulted with Thomas Hardy and Robert Louis Stevenson, and wrote extensively on the philosophy of religion.

And yet, in his own mind, his best ever work was an account of climbing Mont Blanc, by the ordinary route, at sunset.

And now, whilst occupied in drinking in that strange sensation, and allowing our minds to recover their equilibrium from the first staggering shock of astonishment, began the strange spectacle of which we were the sole witnesses. One long delicate cloud, suspended in mid-air just below the sun, was gradually adorning itself with prismatic colouring. Round the limitless horizon ran a faint fog-bank… The long series of western ranges melted into a uniform hue as the sun declined in their rear. Amidst their folds the Lake of Geneva became suddenly lighted up in a faint yellow gleam.

Because yes, to mountaineers at least, Leslie Stephen is known not as the compiler of the Dictionary of Nat Biog, not even as the dad of Virginia Woolf and Vanessa Bell, but as the man who made the first ascents of the Schreckhorn and the Zinal Rothorn. And even more by his book about it, The Playground of Europe (1871), which not only recorded this strange new sport but was also, itself, a major impetus to its development.

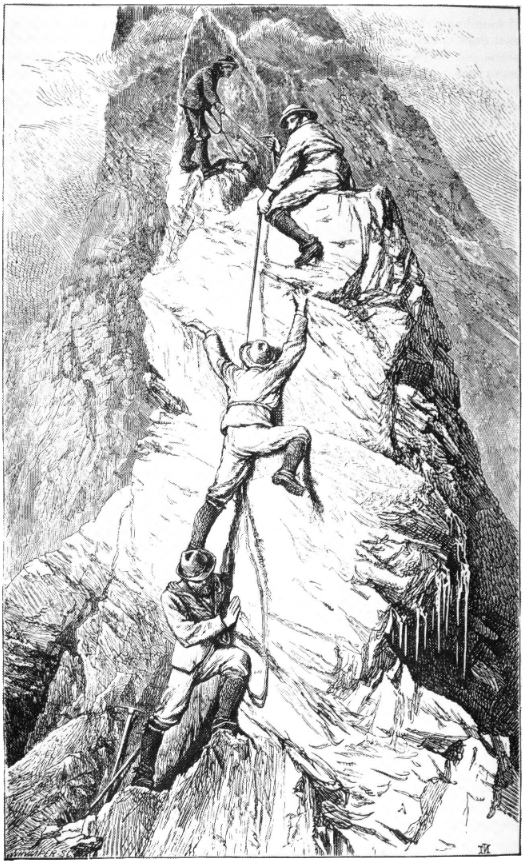

The North Ridge of the Zinalrothorn, from ‘The Playground of Europe’. Exaggerated drawing? This does match with my own memory of the place, but more significantly also with actual photographs

And for sure, The Playground of Europe is read today far more frequently even than ‘Essays on Free Thinking and Plain Speaking (1873). Because whatever we may think of An Agnostic's Apology and Other Essays (1893), ‘Playground’ is an absolute classic of climbing: vivid and amusing, and the north ridge of the Zinal Rothorn remains a lovely climb (AD, rock grade III). I’ve written about the book, and the Zinalrothorn, on UKhillwalking.com.

“Where does Mont Blanc end and where do I begin?”

Mont Blanc, first climbed way back in 1786, wasn’t Leslie Stephens’s very finest piece of climbing – “climbers have ceased to regard his conquest as… anything but a commonplace exploit.” But his was only the third party ever to stand on that summit for the moment of sunset. And, if not his finest ascent, it was his finest piece of Alpine writing – his finest piece of writing overall, in his own estimation, and never mind The History of English Thought in the Eighteenth Century (1876).

With two guides and his friend the painter Gabriel Loppé, he set out from Chamonix early in the morning of 6 Aug 1873. Most climbers today start up the cablecar to the Aiguille du Midi, altitude 3842m. Chamonix is at 1000m: giving them just under 4000m or 13,000ft of ascent, which is almost three times up Ben Nevis.

They took it slowly – they did have all day. Up through the woods and meadows and immediately onto the ice – the glacier came down a lot further in 1873. They will surely have stopped for a mug of wine, chocolate or even coffee at the Grands Mulets, the Alps’ very first mountain hut, which had a warden Silvain Couttet who also built the place.

They continued gently up the glacier, taking time to peer into the crevasses, before heading onto the Dôme du Goûter. As this was the last place with any exposed rocks for sitting down on, they sat there for a while enjoying a view before continuing along the Bosses du Dromadaire to Mont Blanc summit. Which they reached an hour before the expected time of sunset at 8.55pm.

Resting on the Bossons glacier below the Dôme du Goûter. Photo by Gabriel Loppé – the lower figure does look quite like Leslie Stephen, though (given the heavy glass-plate camera) probably not on the same trip.

During that hour of waiting, the wine froze in their water bottles, while M. Loppé was trying to paint in all directions at the same time. “The sense of lonely sublimity was almost oppressive, and although half our party was suffering from sickness, I believe even the guides were moved to a sense of solemn beauty.”

Peak by peak the high snow-fields caught the rosy glow and shone like signal-fires across the dim breadths of delicate twilight. Like Xerxes, we looked over the countless host sinking into rest, but with the rather different reflection, that a hundred years hence they would probably be doing much the same thing, whilst we should long have ceased to take any interest in the performance. And suddenly began a more startling phenomenon. A vast cone, with its apex pointing away from us, seemed to be suddenly cut out from the world beneath; night was within its borders and the twilight still all round; the blue mists were quenched where it fell, and for the instant we could scarcely tell what was the origin of this strange appearance… it was the giant shadow of Mont Blanc.

Immediately they set off down the mountain: they needed to get off the upper slopes before the snow hardened – no crampons in those days, of course. So they took the shorter route by the Mûr de la Cote and the Corridor onto the glacier.1

Rather too many of M. Gabriel’s pictures - if you’re reading on email, and get cut off short, please go back to the top and ‘view in browser’ or ‘read in app’.

Yet as we went the sombre magnificence of the scenery seemed for a time to increase. We were between the day and the night. The western heavens were of the most brilliant blue with spaces of transparent green, whilst a few scattered cloudlets glowed as if with internal fire. To the east the night rushed up furiously, and it was difficult to imagine that the dark purple sky was really cloudless and not blackened by the rising of some portentous storm.

And truly, set in that strange gloom, the moon looked wan and miserable enough ; the lingering sunlight showed by contrast that she was but a feeble source of illumination; … one might fancy that some supernatural cuttlefish was shedding his ink through the heavens to distract her, and that the poor moon had but a bad chance of escaping his clutches.

Soon they were down on the Grand Plateau, safe on the gentler slopes of the main glacier enclosed among the high slopes of ice and rocks. Well, fairly safe (plenty of crevasses!)

At night the icy jaws of the great mountain seem to be enclosing you in a fatal embrace. At this moment there was something half grotesque in its sternness. Light and shade were contrasted in a manner so bold as to be almost bizarre. One half of the cirque was of a pallid white against the night, which was rushing up still blacker and thicker, except that a few daring stars shone out like fiery sparks against a pitchy canopy; the other half, reflecting the black night, was relieved against the last gleams of daylight; in front a vivid band of blood-red light burnt along the horizon, beneath which seemed to lie an abyss of mysterious darkness.

And so down to the Grands Mulets hut, where they spent the rest of the night. I’ve transcribed the full account here.

Leslie Stephens’s climbing days were over before his children were born. But after his death Virginia Woolf recalled “the rusty alpen-stocks2 that leant against the bookcase in the corner; and to the end of his days he would speak of great climbers and explorers with a peculiar mixture of admiration and envy.” In ‘My Father, Leslie Stephen’ she recalls the exciting climbing stories he told to them as children after a happy walk around Kensington Gardens and the Serpentine.

To what extent was he VW’s literary, as well as literal, forbear? During his lifetime, not: she was so intimidated that she couldn’t even start her own writing until he was safely dead. But “Even to-day there may be parents who would doubt the wisdom of allowing a girl of fifteen the free run of a large and quite unexpurgated library. But my father allowed it.”

Her final story, ‘The Symbol’ – which is about the Matterhorn – opens with a mountain sunrise that echoes her dad’s description of Mont Blanc. (My post about that.) And that crayfish up there – the one used to suggest the fading of the moonlight, like squid ink squirted into an aquarium? The little mollusc is back, on the very same inky business, in Woolf’s short story ‘The Lady in the Looking-Glass’. So no, VW is not a mountaineering writer. But, even, the name of a central character in To the Lighthouse, Lily Briscoe, is taken from a mountaineer called Lily Bristow and those exciting Alpine stories she heard from her Dad3.

Mont Blanc at sunrise, Gabriel Loppé

I used this route myself in 1972, though even then it was being considered a bit dodgy due to the retreat of the glacier and its exposure to falling ice and stones. Today it’s never used, possibly because of not getting you anywhere near the cablecar station.

‘Alpine stick,’ a forerunner of the iceaxe but with a much longer shaft

A read-through of ‘To the Lighthouse’, Woolf’s most alpine influenced novel, starts on Feb 1st at ‘Wolfish!’ Its Mr Ramsay is a portrait of Leslie Stephen, and the book, rather surprisingly, is peppered with mountain references.

I enjoyed The Playground of Europe! I'll have to read more of his Mont Blanc essay--I'm planning a Mont Blanc post myself. I was also just thinking about how a To The Lighthouse reread might be in order now that I have Leslie Stephen's own portrayal of himself to compare! Maybe I'll join the readalong...