Too high for breathing flesh

Can you be a mountaineer without ever going up a mountain? If so, then Virginia Woolf was a mountaineer… [1600 words 7 mins

A story is like a mountain: it doesn’t mean anything outside of itself. Which, indeed, is part of what Virginia Woolf’s story ‘A Symbol’ is all about. So if your reaction to the story I linked to last week is, quite simply, to go back and read it from the beginning all over again, I couldn’t criticise that. (I’ve been up Liathach in Wester Ross 17 times, myself.)

If you’re that pure minded person, then skip the rest of this – you’ll just have to wait for Jonathan Otley on Sharp Edge next week. In the meantime, here’s the link to go back to Woolf’s story for the third or fourth time.

For the rest of us: I like this story enough to try, if I can, to add to your appreciation of it with some of its context and surroundings. And for any Woolf scholars who aren’t also mountaineers, there might even be some insight from a mountaineer who isn’t actually a Woolf scholar…

So, a quick summary. An un-named woman is on a balcony in a village that could well be Zermatt, looking at a mountain that could be the Matterhorn – Zermatt is the place which has the graves of the climbers in its churchyard. She’s writing a letter about it to her sister in Birmingham. She has a feeling that the Matterhorn should be a symbol of something, but isn’t quite sure what. Meanwhile, she doesn’t much like the thing.

The viewpoint shifts in a way that matches how the mountain itself is closer or further away depending on the light, or lost in cloud. It opens with an evocation of the deserted mountaintop:

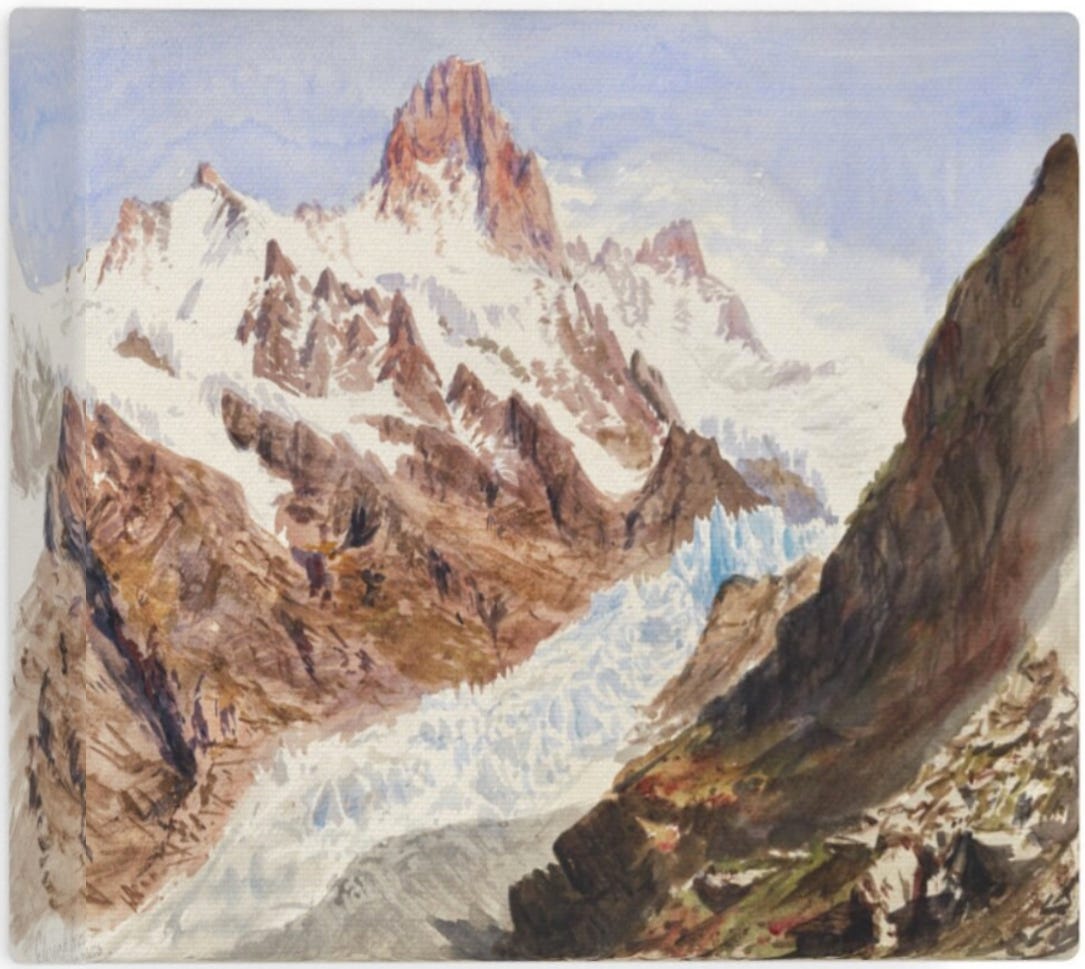

There was a little dent on the top of the mountain like a crater on the moon. It was filled with snow, iridescent like a pigeon’s breast, or dead white. There was a scurry of dry particles now and again, covering nothing. It was too high for breathing flesh or fur-covered life. All the same the snow was iridescent one moment; and blood red; and pure white, according to the day.

– which for me reflects the close of Shelley’s great poem on Mont Blanc, the summit where

… the flakes burn in the setting sun,

Or the star-beams dart through them.1

But at once the viewpoint moves down into the letter-writer’s written words, and then her mind. And the long sentence that makes up the second paragraph, just look at how that’s been put together:

The graves in the valley – for there was a vast descent on either side; first pure rock; snow silted; lower a pine tree gripped a crag; then a solitary hut; then a saucer of pure green; then a cluster of eggshell roofs; at last, at the bottom, a village, an hotel, a cinema, and a graveyard – the graves in the churchyard near the hotel recorded the names of several men who had fallen climbing.

Any editor worth their freelance fee would drag that apart, put it back into the proper order, and ruin it totally.

And now, the first surprise about it: although it’s a deeply serious piece – in the end, it’s about people dying – it’s also curiously playful. As where the letter-writer finds that the Matterhorn reminds her of the Isle of Wight. What, Wight?? And the annoying fellow guest who will continually point out the mountain, the vicar called Mr Bishop.

This playfulness is especially surprising – given that this short story was either the last or the second-from-last thing Woolf ever wrote.2 Three weeks later, she took her own life, drowned in the River Ouse.

Which plunges us straight into the author herself. At what point in her life did she visit the Alps? And why is she writing about a mountain anyway?

When she was in the Alps was – never at all. (It seems that she did once visit Montserrat, near Barcelona, by bus.) But she had been intending this story for several years, just not clear how to go about it given she’d not been on one…. “I would like to write a dream story about the top of a mountain. Now why? About lying in the snow; about rings of colour; silence; and the solitude. I can’t though.”3

And while the story is about a woman looking at the Matterhorn, and stands like the Matterhorn complete in its own meaning or lack of it, it is also – if you want to link back to the author herself – about Woolf’s father. Her distant, domineering, affectionate and much-loved father, the writer, philosopher and former Alpine climber Leslie Stephen.4

Back in the 1860s, before Virginia and her sister Vanessa (later Vanessa Bell) were born, Leslie Stephen was the leading Alpine climber of his time: with his local guide knocking off first ascents of the Schreckhorn and Zinal Rothorn. And compiler of the National Dictionary of Biography though he was, he regarded his time on the mountains as the part of his life that really mattered. As Woolf herself has told us in ‘My Father, Leslie Stephen’:

By the time that his children were growing up, the great days of my father’s life were over. His feats on the river [as an oarsman] and on the mountains had been won before they were born. Relics of them were to be found lying about the house — the silver cup on the study mantelpiece; the rusty alpenstocks that leant against the bookcase in the corner; and to the end of his days he would speak of great climbers and explorers with a peculiar mixture of admiration and envy.

On the streets of London he still wore the long tweed coat he’d climbed Mont Blanc in, proudly showing the marks left on it by the rope.

So that, in ‘A Symbol’, the innkeeper Melchior shares his name with Leslie Stephen’s Alpine guide, Melchior Anderegg. So that, in this story, Woolf only half remembers the details of the Matterhorn disaster (Whymper’s 1871 account of it was book-reviewed by Leslie Stephen). It’s not important, but the four who died in the 1860s were the ones whose rope broke, rather than the ones who froze to death.

So that, in ‘To the Lighthouse’, the character who seems to be based on Woolf herself, the painter Lily Briscoe, has borrowed her name from an independent-spirited mountain climber of the 1890s, Lily Bristow.5

And so that this, Woolf’s final story, revisits the theme of the ‘meaning of Mountains’ from the Mont Blanc sunset in Chapter 11 of ‘Playground of Europe’. According to Virginia Woolf, Stephen himself, eminent man of letters, considered this chapter the best thing he ever wrote.

The snow at our feet was glowing with rich light, and the shadows in our footsteps a vivid green by the contrast. Beneath us was a vast horizontal floor of thin level mists suspended in mid-air, spread like a canopy over the whole boundless landscape, and tinged with every hue of sunset. Above us rose the solemn mass of Mont Blanc in the richest glow of an Alpine sunset. The sense of lonely sublimity was almost oppressive…

The huge shadow [of the mountain], looking ever more strange and magical … climbed into the dark region where the broader shadow of the world was rising into th eastern sky.

Readers of ‘To the Lighthouse’, where Mr Ramsay is based on Leslie Stephen, come away with his domineering and bossy nature. But Woolf’s attitude to her father was more complex: shown in her account of him I quoted further up. And she suffered through his long-drawn-out final illness in the same way as the letterwriter of ‘A Symbol’ did on the Isle of Wight.

What is it then, the Meaning of Mountain? The story’s letter writer can’t work it out. Leslie Stephen says the only way to show you is by tying you onto his rope and taking you up there – even as, in effective Victorian prose, he’s showing you exactly that.

But there’s a reason the Matterhorn reminds us of the Isle of Wight, where the letter-writer’s mother took so long to die. The long haul to the top: the expectation that once there, life will be changed and different, she can marry her fiancé, the mountain will be climbed. But of course, the only final ending is death itself.

We can be pretty sure that, whatever the letter-writer thinks, the mountain isn’t a symbol of anything at all. Writing about the lighthouse in ‘To the Lighthouse’:

I meant nothing by The Lighthouse… I saw that all sorts of feelings would accrue to this, but I refused to think them out, and trusted that people would make it the deposit for their own emotions—which they have done, one thinking it means one thing another another. I can't manage Symbolism except in this vague, generalised way. Directly I’m told what a thing means, it becomes hateful to me. [Letter to Roger Fry 1927, Woolf’s italics].

Indeed, the story can be read as a simple tease against those trying to read symbols into ‘Mrs Dalloway’ and ‘To the Lighthouse’.

Because back in the story’s opening paragraph, in Shelley’s poem, in Leslie Stephen’s account of Mont Blanc: the mountain exists alone, and of itself, independent of the lives of those looking up at it or climbing and dying there.

And this is true, too, of Virginia Woolf’s final short story.

It’s a long poem - probably longer than Virginia Woolf’s story. My summary of it is on UKhillwalking.com here.

The other being a story called ‘The Ladies’ Lavatory’, or possibly ‘The Watering Place’, set in a women’s toilet.

Diary, June 1937; quoted by Catherine Dent ‘The Ties that Bind: Virginia Woolf, Leslie Stephen, and Ancestral Mountains’: Movable Type 13. Her useful discussion is online here.

My article about Leslie Stephen and ‘The Playground of Europe’, his classic account of his climbs in the Alps, is on UKclimbing.com .

To the Lighthouse, set entirely at the seaside, has a remarkable number of mountain references: including one where non-mountaineer Mr Ramsay imagines himself as dying on some lonely summit. “He would find some crag of rock, and there, his eyes fixed on the storm, trying to the end to pierce the darkness, he would die standing.” One of these days I’ll be posting here about Lily Bristow (mountaineer) and Lily Briscoe (character in ‘To the Lighthouse’).

How interesting. I didn't know any of that about VW's father.

I found this story really interesting. This line caught my attention: the woman writes to her sister: 'The mountain just now reminded me how when I was alone, I would fix my eyes upon [our mother's] death, as a symbol.' It struck me that the letter writer has things upside-down - surely 'death' is nearly the only thing that can never be a symbol of something else; it is complete in itself and carries always its own valency. It cannot be a stand in - everything else is lesser.

I liked the atmosphere created by the presence of the mountain everywhere - up at such a high altitude, things lacking consequence drop away. One is near something grave and momentous. It's visible through every window. Everything that seems important in everyday life loses its substance up high: 'So little that was solid could be dragged to this height.'

Honorable mention to the anchovies being served up along with the Rev. Bishop.