What’s with these waterfalls?

For well over 1000 years, we’ve been chasing around after falling water. So what’s so special about noise, frothy whiteness, and getting wet with the splashing?

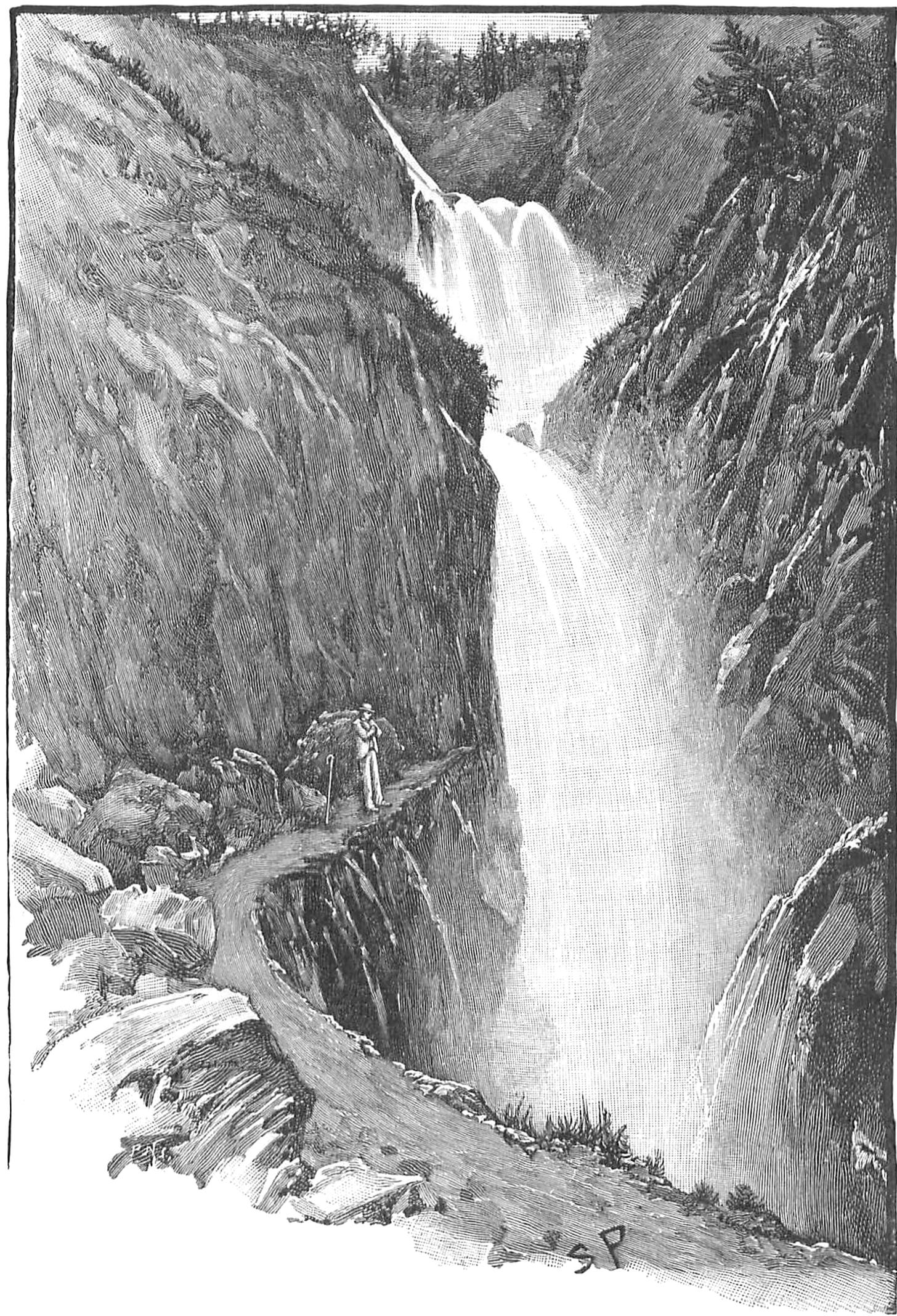

It is, indeed, a fearful place. The torrent, swollen by the melting snow, plunges into a tremendous abyss, from which the spray rolls up like the smoke from a burning house. The shaft into which the river hurls itself is an immense chasm, lined by glistening, coal-black rock, and narrowing into a creaming, boiling pit of incalculable depth, which brims over and shoots the stream onward over its jagged lip. The long sweep of green water roaring for ever down, and the thick flickering curtain of spray hissing for ever upwards, turn a man giddy with their constant whirl and clamour. We stood near the edge peering down at the gleam of the breaking water far below us against the black rocks, and listening to the half-human shout which came booming up with the spray out of the abyss.

“You expect the countryside to be quiet,” said the management trainee who’d just spent five hours under a small green tarp above Seathwaite, alone with her thoughts and a bottle of midge repellent. But the countryside is not quiet. All morning she’d been subjected to sheep wandering about and going Baa. As the sheep settled to chew the cud, there emerged the sound of Grange Gill, and the higher-pitched rustle of the two nearby waterfalls, Taylorgill and Sour Milk Gill. And behind them, the rumble of the usual aeroplane, for Lakeland is directly under Easyjet to Glasgow International and Virgin to the USA.

Waterfalls and aeroplanes sound remarkably similar, considering that waterfalls are romantic wild nature while aeroplanes are noise….

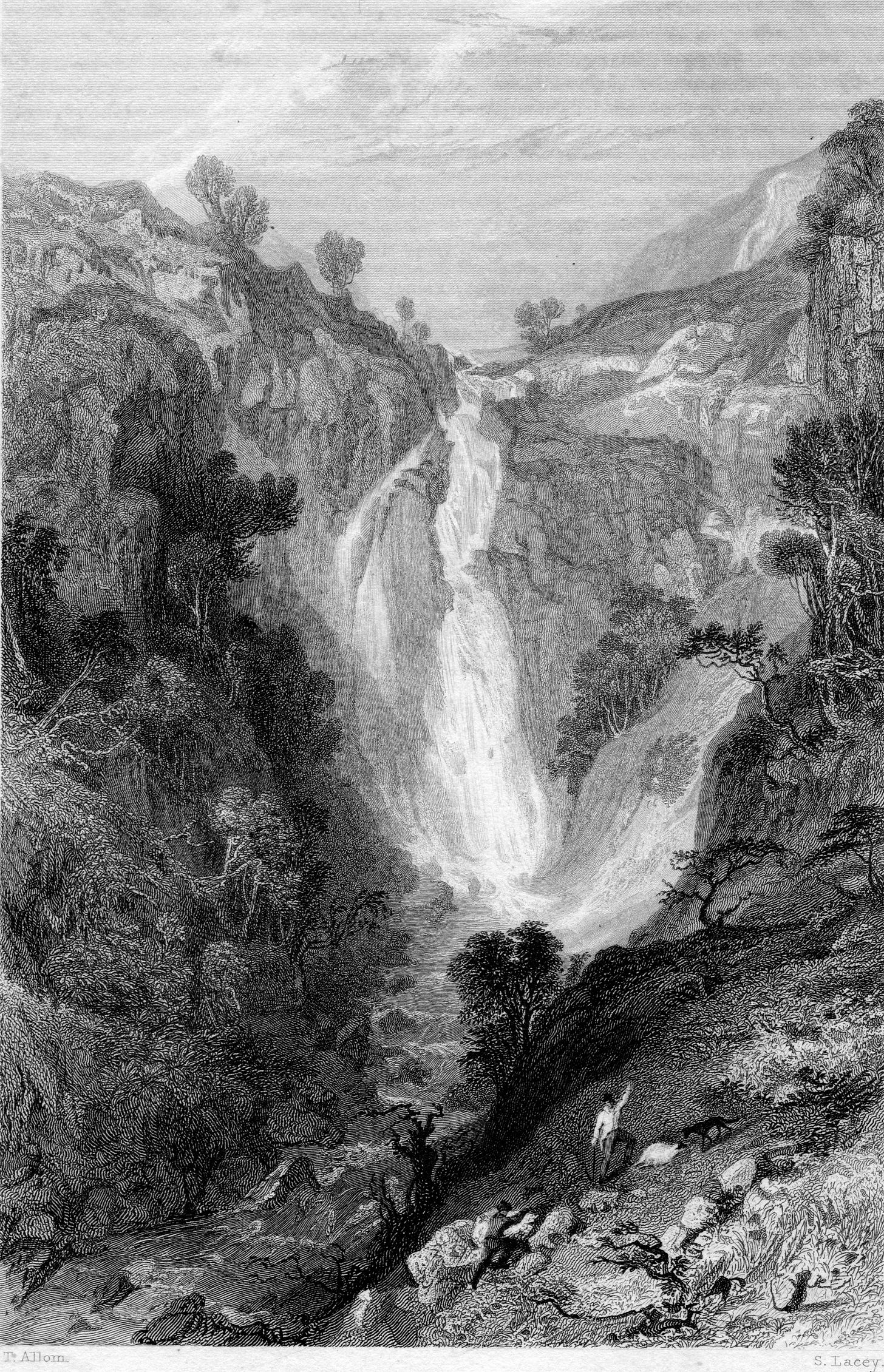

For centuries, perhaps millennia, we humans have been chasing after waterfalls. According to Walter Scott, Scottish Highlanders in ancient times had themselves sewn into the skin of a slaughtered bull and left out in the spray, simply so’s to experience some prophetic visions.1 Chinese sages of both the Confucian and the Taoist persuasion set up viewing platforms to admire streams dropping off cliffs: the “Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove” were at it as early as the fourth century in China and by the ninth century in Japan. Which is why, fifty years after Thomas Allom was applying ‘Force of the Imagination’ to Taylor Gill, on the other side of the world Katsushika Hokusai was making his own ‘Tour of Waterfalls in Various Provinces’.2

The Sounding Cataract

Haunted me like a passion

– so wrote William Wordsworth of his early years when it was just him and the hill, and no need to write it all down and find rhymes for it. In the last, harsh days of 1799, he and his sister Dorothy crossed the Pennines, thirty-mile days along the frozen roads of Wensleydale, specifically in search of its waterfalls.3 They’d already bagged five of them by the time they came to Hardraw Force.

After cautiously sounding our way over stones of all colours and sizes, encased in the clearest water formed by the spray of the fall, we found the rock, which had before appeared like a wall, extending itself over our heads like the ceiling of a huge cave, from the summit of which the water shot directly over our heads into a basin, and among the fragments wrinkled over with masses of ice as white as snow, or rather, as Dorothy said, like congealed froth. The water fell at least tens yards from us and we stood directly behind it, the excavation not so deep in the rock as to impress any feeling of darkness, but lofty and magnificent; but in connection with the adjoining banks excluding as much of the sky as could well be spared from a scene so exquisitely beautiful.

The spot where we stood was as dry as the chamber in which I am now sitting, and the incumbent rock, of which the groundwork was limestone, was veined and dappled with colours which melted into each other with every possible variety of colour. On the summit of the cave were three festoons, or rather wrinkles, in the rock, run up parallel like the folds of a curtain when it is drawn up. Each of these was hung with icicles of various lengths, and nearly in the middle of the festoon in the deepest valley of the waves that ran parallel to each other the stream shot from the rows of icicles in irregular fits of strength, and with a body of water that varied every moment. Some-times the stream shot into the basin in one continued current; sometimes it was interrupted almost in the midst of its fall, and was blown like the heaviest thunder-shower towards part of the waterfall at no great distance from our feet.

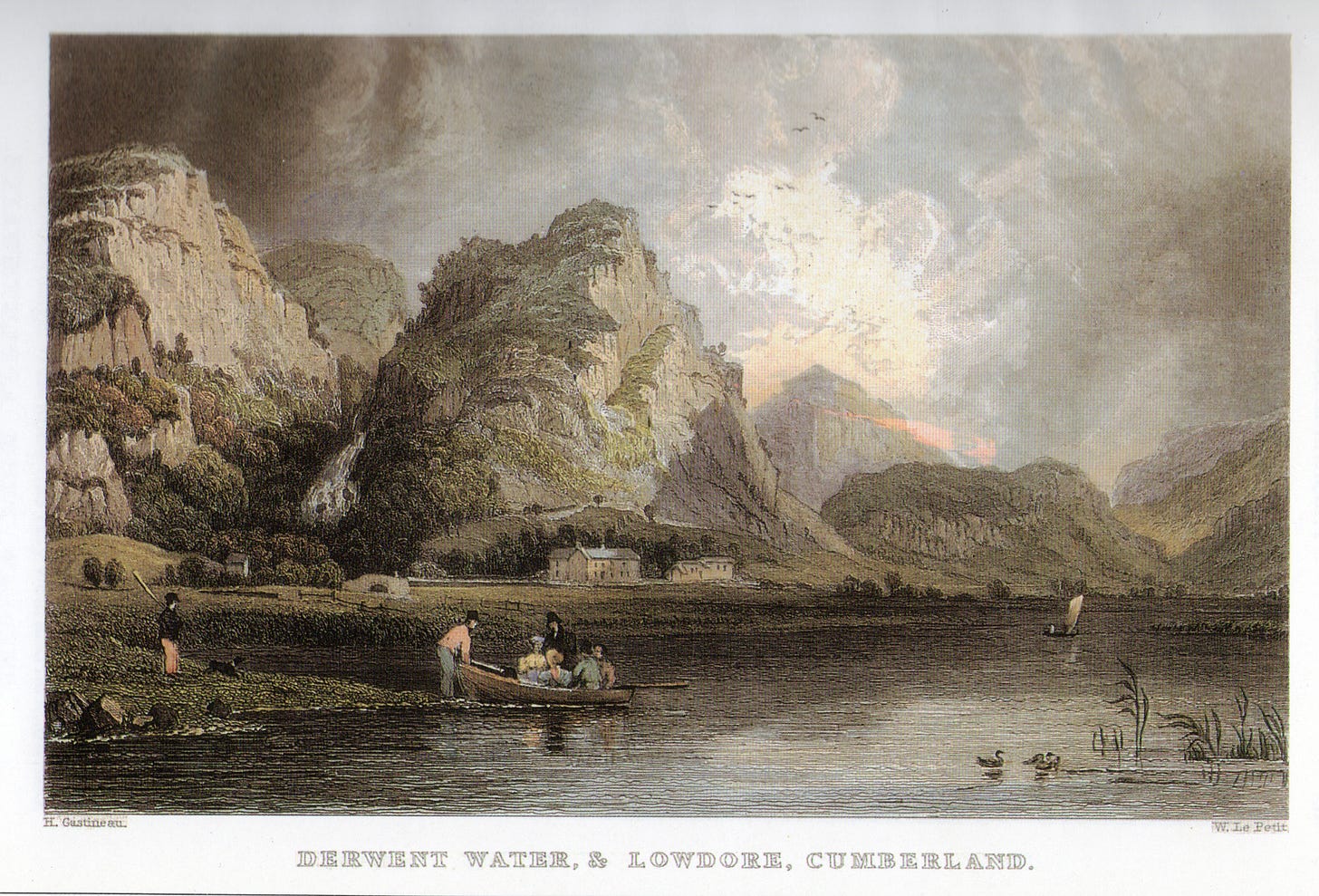

Once settled at Grasmere, the two of them were off up Easedale to thrill to Sour Milk Gill (Churnmilk Force, it was called in the early 1800s). A few years later, Robert Southey treated Lodore Falls to a spate of gushing, tumbling, frothing, ceaselessly-seething poetic epithets. And early painters of the Lake District showed Rydal Falls rather oftener than Scafell.

If Wordsworth himself never rhymed up a waterfall, it could be because of his friend Coleridge's 'Kubla Khan', the first great Romantic poem, thundering away in his ear.

And from this chasm, in ceaseless tumult seething

As if the earth in fast thick pants were breathing

A mighty fountain momently was forced.

So what is it with these waterfalls?

I was disappointed with Niagara – most people must be disappointed with Niagara. Every American bride is taken there, and the sight of the stupendous waterfall must be one of the earliest, if not the keenest, disappointments in American married life.

Oscar Wilde ‘Impressions of America’

A waterfall, in some respects, is rather like a motorway. Walk up Spooney Green Lane out of Keswick on your way up Skiddaw, and pause above the A66. The continuous shifting roar is almost identical with the sound of falling water below the ornamental footbridge at Aira Force, in some stormy Autumn. The flickering motion below is also much the same, except that the dual carriageway is more interesting as there’s more going on. And as for the torrent’s awesome power and force, you'd be every bit as dead if you toppled over into the stream of juggernauts heading for Workington. The juggernauts smell of diesel: Aira Force smells of rotting leaves with a hint of methane.

And yet, some of us will drive through the floods to stand above Aira in spate. Whereas few if any of us get our kicks from the A66.

Now if you were a grizzly bear, it’d all be obvious enough. This nice splashy waterfall, with the big bouldery bits on either side, neat! Head back here come September and claw some nice tasty salmon out of the water. But as mere humans, waterfall noise, we’d think, would be something to avoid. A leopard could creep up on us, or even a sabre-tooth tiger.

Looking at it the other way, though, we are ourselves a formidable predator. Maybe our instincts favour the sounding cataract exactly because it helps us to sneak up on some unsuspecting bunny rabbit or baby deer.

Turning from soggy biology to hard neuroscience, some psychologist has disclosed that the reason our sofas form a circle around our TV sets is because of a fundamental human feeling for a source of flickering light. Neighbours or Big Brother is today’s version of the caveman’s camp fire. And waterfalls do resemble soap opera in one, important way: they keep on moving about but nothing ever actually happens. And so, once Wimbledon fortnight’s finally over, it’s time to switch off my own TV and head out looking for some waterfalls.

Then again, there is that comforting white noise, like those little machines you clip to your baby’s bedside. Studies have shown that offered the sound of a waterfall, and the related white noise of a nearby motorway, humans who expressed a preference were pretty keen on the sound of the old M74. Mind you, when I slept out on the Annandale Way, it was just about possible to tell the difference. The motorway’s occasional clanking wagon meant that it could only really stand in for a stream if that stream had some large lumps of scrap iron being carried along in the current.

In an article on WebMD, Pierce J. Howard, PhD, the author of The Owner’s Manual for the Brain: Everyday Applications from Mind Brain Research tells us: “Generally speaking, negative ions increase the flow of oxygen to the brain; resulting in higher alertness, decreased drowsiness, and more mental energy.”

Having passed through the lungs into the bloodstream, somehow managing to not shed that surplus electron on the way in, the negative ions make their way to the cells lining one’s gastrointestinal tract4. Here they are believed to produce biochemical reactions that increase levels of the mood hormone serotonin5, helping to alleviate depression, relieve stress, and boost our daytime energy.

“Believed”, that is, by freelance health writer Denise Mann. For myself, I can find this sort of Sunday Supplement neuroscience a bit annoying. Meanwhile, do we have a family member who spends too long in the shower? Reason for that being, they’re suffering from endorphin addiction brought on by all those negative ions…

I need a nice waterfall to calm down beside.

Notes to ‘Rob Roy’. Mind you, Walter was a waterfall-watcher himself, so if he was going to make up an interesting legend this is the sort of interesting legend he might make up.

That’s ‘Shokoku taki meguri’, for my Japanese-speaking subscriber. (Hullo, Jess!)

Well, they were also economising on the cost of the coach.

(or else, possibly, to the raphe nuclei in the brainstem)

The precise biochemical mechanism is yet to be determined

Never not funny. 😅 My most recent splendid waterfall experience was dropping down from an An Teallach bivvy in the early morning sunshine towards Dundonell. Nothing like a crack of dawn dip in a waterfall. Only to find a larger, even nicer one 5 min down the trail surrounded by beautiful pine. Scotland never disappoints.

Nowtl like a good waterfall! Interesting thoughts, curiouser and curiouser...