Two snowy poems

The appropriately named Robert Frost and his compatriot Wallace Stephens help us say goodbye to Winter. Plus a conundrum on copyright [1200 words 6 mins

Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening

Robert Frost 1923

Whose woods these are I think I know.

His house is in the village though;

He will not see me stopping here

To watch his woods fill up with snow.

My little horse must think it queer

To stop without a farmhouse near

Between the woods and frozen lake

The darkest evening of the year.

He gives his harness bells a shake

To ask if there is some mistake.

The only other sound’s the sweep

Of easy wind and downy flake.

The woods are lovely, dark and deep,

But I have promises to keep,

And miles to go before I sleep,

And miles to go before I sleep.

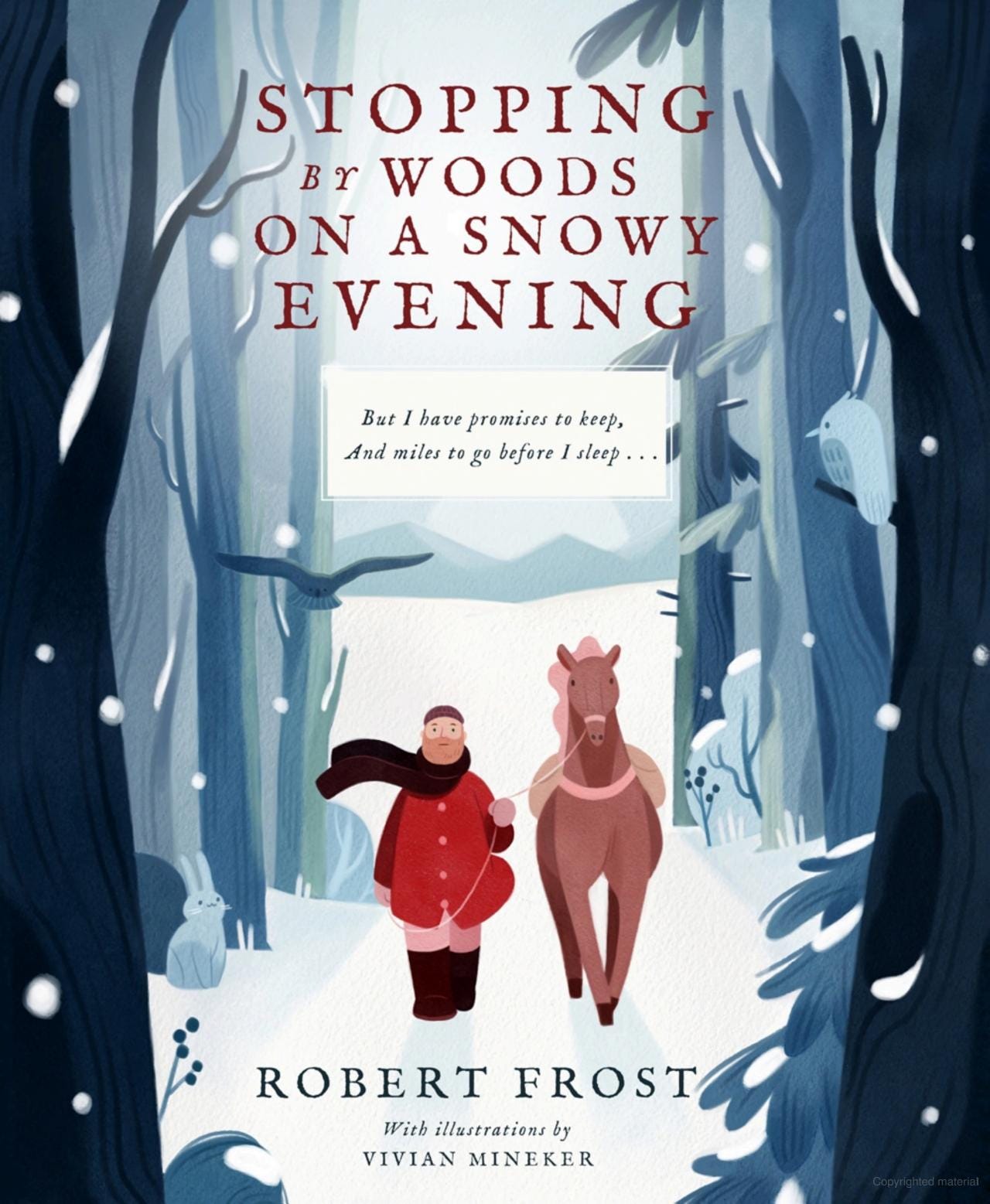

A simple (or apparently simple) and well loved poem: and really, the ebook version illustrated by Vivian Mineker says it all…

Frost considered that a real poet was one who left even a handful of poems embedded in the language. And this poem is one of them.

The speech rhythms are quite1 natural, and yet run out in perfect iambic tetrameter (four ‘feet’ each going di-DAH) with just one exception, the first two words of the poem, which go DAH-di (a trochee) or perhaps DAH DAH (a spondee). The remoteness and emptiness of the woods are indicated, obliquely, by evoking the owner in the distant village; and then again at the end, where it’s already getting dark and the poet has a long way yet to go.

And it’s only because it was published in ‘The New Republic’ rather than anywhere here in the Old Kingdom, that I’m allowed to put it up on my Scotland-based Substack.

Although Substack itself lives in San Francisco, California, I’m in Scotland UK and I count as the publisher here. For a bit of fun, here’s a sneaky copyright quiz. Which of the following is out of copyright (or ‘public domain’) here in the UK? Answers are below the picture, explanations in a footnote.

1. The Waste Land (1922) by TS Eliot (1888 – 1965)

2. Fern Hill (1945) by Dylan Thomas (1914 – 1953)

3. The Snow Man (1921) by Wallace Stephens (1879 – 2 Aug 1955)

4. The Poem that took the Place of a Mountain (1954) also by Wallace Stephens

5. Mending Wall (1914) by Robert Frost (1874 – 1963)

Answers: Waste Land NO (but yes in US); Fern Hill YES (but I believe no in US); Snow Man YES (in both UK and US); Mountain NO (in either UK or US); Mending Wall NO (but yes in US)2

Now for a deeper look into the winter’s bleakness, in a poem published just two years before…

The Snow Man

Wallace Stephens (1921)

One must have a mind of winter

To regard the frost and the boughs

Of the pine-trees crusted with snow;

And have been cold a long time

To behold the junipers shagged with ice,

The spruces rough in the distant glitter

Of the January sun; and not to think

Of any misery in the sound of the wind,

In the sound of a few leaves,

Which is the sound of the land

Full of the same wind

That is blowing in the same bare place

For the listener, who listens in the snow,

And, nothing himself, beholds

Nothing that is not there and the nothing that is.

Same length as the first one, did you spot? At least if we don’t count Robert Frost’s repeated final line. And at first read-through it seems to be about bleakness and misery, much the same. But in fact it’s going further than that.

Each of Robert Frost’s four stanzas ends as a complete sentence. But ‘The Snow Man’ is a single sentence, right the way through. And the syntax is tricky. It’s actually saying that:

• You would have to have a mind of winter

• To see the pine trees etc

•And not think of misery in the sound of the wind

What do you think when you look at this bleak winter scene? Okay, maybe it makes you think of Christmas or ski trips or superb ice climbs above Glen Coe… But for most of us observers, there’s something sad about the bare trees and the black-and-white landscape.

And what about the sound of a few dry leaves, left over from autumn, blowing across the hard-frozen snow. Something a bit dismal about it, wouldn’t you agree?

But Wallace Stephens’ poem invites us, if we can, to view the scene without those poetic associations. To see the scene simply as it is, with the “mind of winter”. With the mind, indeed, of the Snow Man.

‘Modernism’ – the term’s not very informative. It just means Eliot and Virginia Woolf and Ezra Pound and the others came after whatever came before them. But initially, these poets were called ‘Imagists’. Meaning they weren’t so concerned with meaning, more with the pictures and the pattern of ideas they were transferring into our visualising minds through our reading eyes.

So the message is – am I banging a tired old drum that only I can hear? – similar to the one I drew from Woolf’s ‘The Symbol’ back last year. There is no symbol. The Matterhorn is simply and absolutely itself.

And here, Stephens is inviting us to consider the winter landscape, simply as it is, without any of the emotions and associations we normally smear across the scenes before our eyes.

To see “nothing that is not there” – to eliminate all those snowy emotional resonances that just come out of our own minds and preconceptions

But also, ‘the nothing that is’ – so, to see past our own projections and preconceptions, to the actual Nothingness, as experienced by the Snowman with his ‘mind of winter’.

It’s a whole extra level of winter bleakness…

UK-type ‘quite’ here to mean ‘entirely’. Although in UK ‘quite’ can also mean ‘somewhat’, as in America. Sorry!

In the UK, copyright lasts for 70 years from the author’s death, and then to the following 1st January. So ‘Fern Hill’ came into the public domain on 1st January 2024, while ‘The Waste Land’ is still in copyright.

In the US, copyright expires 95 years after publication. And so, in the US, ‘The Waste Land’ is in the public domain while ‘Fern Hill’ isn’t. (It might be the case that ‘Fern Hill’ and other UK-published works that are out of copyright here in the UK are also public domain in the US. Or it might not.)

However, where a work originated and was first published in the US, and is public domain there, then it’s also out of copyright in the UK. And so ‘Stopping by Woods’ and ‘The Snow Man’ are both available for my UK-based Substack. (Although Eliot was in 1922 still a US citizen, ‘The Waste Land’ was originally published in London.) Meanwhile ‘Poem that took the Place of a Mountain’ comes out of copyright, UK style, on 1st January next year. (And I’ll be publishing it here on Wed 2nd.)

So what about ‘Mending Wall’? This is a tricky one. In 1914 Robert Frost was living in England with his friend and fellow poet Edward Thomas, and the collection ‘North of Boston’ was first published in London. So the UK 70-years-from-death rule applies, and I can’t use it here until 2034. Unless I emigrate to Trumpland. (Or China, where they have a 50-year rule.)

“Descend lower, descend only,” says TS Eliot in ‘Burnt Norton’ (protected until 2036 in the UK, 2032 in the US, but I’m okay under the ‘quotation’ fair-dealing exception to copyright). What if I wanted to republish the Pulizer Prize winning Bridge of San Luis Rey (1927) by Thornton Wilder (1897–1975)? Under the US 95-years-from-publication rule, it’s been public domain since 2018. But under the Berne Convention’s minimum 50-years-from-death rule, it’s protected until the end of this year. And while Eritrea and Kosovo aren’t signatories to the Berne Convention, the US is…