The trip into the mountains

Very short short-story by Franz Kafka [1100 words, 5 mins

Franz Kafka: author of 'The Trial' and 'The Castle' and that story about Gregor Samsa who wakes up and finds he's turned into a giant beetle. Kafka is a towering genius of European literature; but, it's generally agreed, a pretty tough read.1

So - would you like to say you've read Kafka, but without the hassle of working your way through the 208 pages of bureaucratic paranoia that's 'The Trial'? Well, you can. Because here he is, concentrated down into a story of just 167 words.

Better still, it's a story about the mountains.

The trip into the mountains

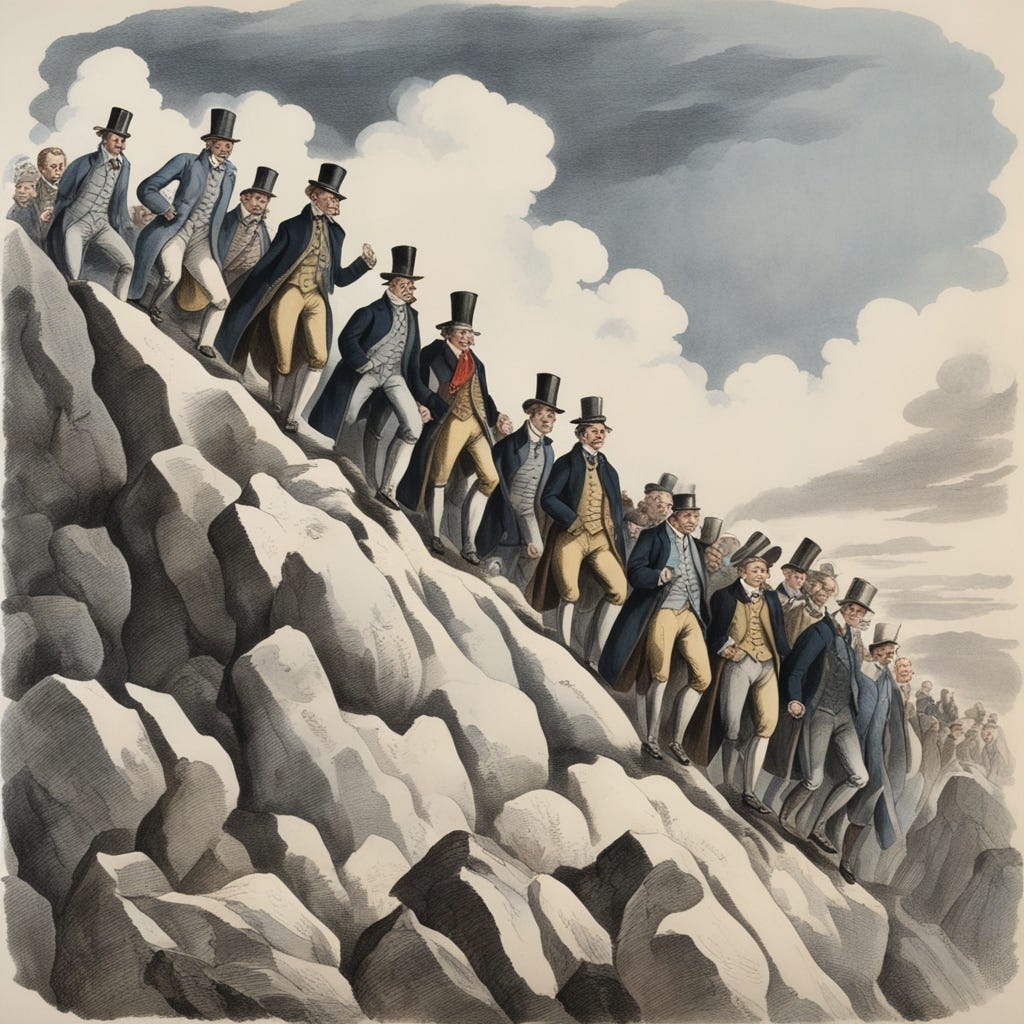

“I don’t know,” I cry out tonelessly, “I really don’t know. If nobody comes, then okay, nobody comes. I haven’t given anybody any aggravation, nobody’s caused any aggravation to me, but nobody’s going to help me. Absolutely nobody. That’s just the way it is. Just because nobody’s going to help me – otherwise, a whole group of utter Nobodies would be quite a pretty thing. What I’d really like – and why not? To get up an expedition with a company of utter Nobodies. Of course up into the mountains, where else? How these Nobodies crowd up against each other, all their outstretched arms tangled together, the multitude of feet pacing out tiny steps in those lacquered shoes with their leather soles! It’s understood that all are in tail coats and top hat. We walk just so-so, the wind travels through the gaps that we leave open between our limbs. In the mountains, our throats will be free! It’s amazing that we don't all burst out into song.”

Der Ausflug ins Gebirge (1913) Translated RT with help from Google Translate and my friend Zvonko Kracun who explained the formal "Frack" outfit of German-speaking eastern Europe. A more classy translation by Willa and Edwin (the poet) Muir is here. (If you move in the sort of circles where you only impress by going 'oh I've read Kafka in the original', the German is in the footnotes below.2)

Franz Kafka (born 1883) grew up in Prague in an upper-middle class Jewish family – his grandfather was a ritual slaughterer. With an oppressive but largely absent businessman father (the business being foundation garments for ladies), his mother also absent working in the business, he was raised by servants and governesses. Two brothers died in infancy, but he grew up alongside three sisters.

From 1907 he was an office worker in the outer reaches of the Austro-Hungarian Empire; initially working ten-hour days in an insurance office, then a slightly less unsatisfactory job at the Worker's Accident Insurance Institute for the Kingdom of Bohemia. He was good at the job, and got promoted.

As a Jew, he was already set apart from the mainstream German-speaking culture around him: a culture that two decades later would be murdering his entire race. (Kafka died young, but the Holocaust took all three of his sisters.) But as a secular Jew, he wasn't even integrated into his own ethnic group. Equally, as a representative of the colonial power he was set apart from the Czech-speaking Bohemians around him. With a strong but frustrated sex-drive (hetero, but unpublished diaries reveal repressed homoerotic desires) he had trouble forming steady relationships, a user of pornography and brothels. And at work he was tangled into what may have been the most dense and compounded bureaucracy developed anywhere before the digital age.

With this biography it's no surprise that he becomes the poet and priest of alienation.

However, he seems to have been close to his three younger sisters. The few friends he did have found him interesting, insightful and – yes – fun to be with. And on weekends they embarked on long hikes, often planned by Kafka himself.3 He also spent time in a tuberculosis sanatorium in the High Tatras, that magnificent (and very crowded) granite range on the border of today's Poland and Slovakia.

His hikes must have been limited by his many health issues: clinical depression, social anxiety, migraines, insomnia, constipation, boils, and the tuberculosis that would end his life at the age of 40. Even so, the mountains meant a lot to him. We can be pretty sure that without his time in the Tatras his life would have been even more miserable than it was.

Published as a free-standing short-short in 1914, 'The Trip into the Mountains' (Der Ausflug ins Gebirge) was also embedded within a longer work, 'Diversions, or a Proof That It's Impossible to Live'. Which is a dream hiking-trip that, yes, along with the surreal angst and paranoia we associate as 'Kafkaesque' is full of the joys of a nice long walk.

Opposite and at some distance from my road, probably separated from it by a river as well, I caused to rise an enormously high mountain whose plateau, overgrown with brushwood, bordered on the sky. I could see quite clearly the little ramifications of the highest branches and their movements. This sight, ordinary as it may be, made me so happy that I, as a small bird on a twig of those distant scrubby bushes, forgot to let the moon come up. It lay already behind the mountain, no doubt angry at the delay.

For the Mountain Trip story, my imagination supplies a crowd of homeward commuters, in black suits and bowler hats, filling the evening street of Prague. We are in distress, we need help. But preoccupied and enclosed in the moving crowd, our bodies packed together, that doesn't mean there's any human contact here…

A crowd passed over London Bridge so many

I did not know death had undone so many

wrote his fellow office-worker TS Eliot six years later.4

But then, the superb, surreal transfer onto a ridge of the mountains. Yes, it's a sort of (German-speaking, alienated) joke effect. Am I wrong? In my post back in March, the mountain story by Virginia Woolf, another notably not-humorous writer, also came across to me as a bit of a tease…

In the mountains, there you feel free – TS Eliot again

And so in the crowd of black-suited commuters, feeling the wind on our bodies, the open spaces around – we all burst into song.

Well this is Kafka so we don't actually burst into song. But we almost do. And how bizarre that this perhaps simple story, expressing the joy of the mountaintop, comes from the paranoid pen of Europe's most angst-ridden author.

Happy Kafka!

Somewhere between a giant beetle and a giant centipede, actually.

Der Ausflug ins Gebirge (Franz Kafka 1913)

„Ich weiß nicht“, rief ich ohne Klang, „ich weiß ja nicht. Wenn niemand kommt, dann kommt eben niemand. Ich habe niemandem etwas Böses getan, niemand hat mir etwas Böses getan, niemand aber will mir helfen. Lauter niemand. Aber so ist es doch nicht. Nur daß mir niemand hilft —, sonst wäre lauter Niemand hübsch. Ich würde ganz gern — warum denn nicht — einen Ausflug mit einer Gesellschaft von lauter Niemand machen. Natürlich ins Gebirge, wohin denn sonst? Wie sich diese Niemand aneinanderdringen, diese vielen quergestreckten und eingehängten Arme, diese vielen Füße, durch winzige Schritte getrennt! Versteht sich, daß alle in Frack sind. Wir gehen so lala, der Wind fährt durch die Lücken, die wir und unsere Gliedmaßen offen lassen. Die Hälse werden im Gebirge frei! Es ist ein Wunder, daß wir nicht singen.“

A sentence from Max Brod’s biography reproduced on Wikipedia. Without spending a whole lot more time on research I can’t find any details of where the hikes went, or just how long they were.

The Waste Land 1922, the second line a quote from Dante's Inferno.