Sophia Delaval: 18th-century outdoor type

Aristocrat, influencer, and serious landscape appreciator [1300 words, 6 mins

Aristocracy, if it means anything at all, involves scandals and some serious eccentricity. It means being up with all the latest fads and fashions: and not just being up with them all, but an actual influencer. Plus, doing it properly, you ought to be commissioning some serious works of art and architecture.

The Delavals, an unusually dissolute and ill-fated aristocratic family from Seaton Delaval in Northumberland, fit the definition to a tee (or tee-square).

Vice Admiral George Delaval made his pile with prize money from the War of the Spanish Succession. His cousin Sir John Deleval, 3rd Baronet, had gone bankrupt, and the admiral snipped up the family estate. (Thus pre-enacting the fate of Kellynch Hall in Jane Austen’s Persuasion.1) The admiral then commissioned top architect Sir John Vanbrugh to spruce the old place up. Hopeless, said Sir John Vanbrugh. Let’s knock the whole thing down and start again from scratch.2

Before it was even finished, the admiral died in a fall from his horse while galloping around the estate – leaving it to his nephew Captain Francis Blake Delaval. Who managed to avoid falling off his own horse; instead he fell down the front steps, in December 1752.3 Leaving the Hall to his son John. Sorry, that would be ‘John Delaval 1st Baron Delaval of Seaton Delaval’.

So it was up to the next generation, to cultivate an appropriate level of aristocratic excess. John, who would be the father of landscape-lover Sophia Anne, was one of 11 brothers and sisters: he was the second son, but got the house and estate because of being slightly more sensible than his elder brother Francis.4 The overcrowded house was enlivened with amateur theatricals from the family and professional ones from any passing group of actors. Out on the terrace there could be rope dancers, a conjurer or some dancing bears.

The garden parties were to-go-to. The banquets were sumptuous. The one drawback to visiting Seaton Delaval was Uncle Francis’s practical jokes. One room had walls that, when the guest was undressed and ready for bed, could be wound down into the floor. Another offered a bed that, again by mechanical means, could be suddenly lowered into a tank of cold water. Then there was the room with the blacked out windows where a heavy-drinking guest once slept through three nights and two days before wondering what the heck had happened to tomorrow.

But maybe the worst, when waking up with a fuzzy memory and a sore head from the night before, was the upside-down room: chairs and bedside furniture hanging from the ceiling, the chandelier rising upwards out of the floor…

Amidst this happy confusion, Sophia with her brother and five sisters grew up (or in several cases died in childhood) pretty much under their own steam. A painting of her aged 18 shows her in front of a romantic seaside sunset, holding a mandolin the wrong way around and looking slightly bewildered.

Already we see her taste for some Romantic Landscape to set off the lacy dresses. For Sophia Anne took her 18th-century behaviour seriously. Aged 26, Sophie returned from her Grand Tour of Europe ‘sort-of-married’ to a Mr Henry Devereux, whom she had left behind in Bordeaux. (One source suggests that not just the marriage but Mr Devereux himself was a polite fiction invented by the family to slightly reduce the scandal.) After the birth of her son she headed back to France for a second Grand Tour, acquiring (just like Lydia Bennet in ‘Pride and Prejudice’) a young army officer, ensign John Jadis of the 59th Regiment of Foot, as her second ‘sort-of-husband’. As in Jane Austen’s book, her father Lord Delaval hastily arranges a proper English wedding and an annual payment of £500 to Ensign Jadis.

Jane Austen doesn’t give us the future life of Lydia and Mr Wickham; Sophie Anne’s outcome could supply a hint. After a duel with Sophie’s brother-in-law Lord Tyrconnel (actually just a challenge, nobody got killed) Jadis is ejected from Seaton Delaval, and paid off with a reduced allowance of £100 a year. Which may even have left him ahead of the game, as he no longer had to support Sophia Anne’s hairstyles or, indeed, her opium habit.

Meanwhile, as all this was going on, a vicar from Hampshire called William Gilpin was inventing the strange craze for pretending that England was actually an oil-painting by Claude Lorrain (‘Observations on the River Wye’ 1782).5 Within the next 10 years it would lead to Lakeland, the Peak District, and other Instagram hotspots of the late 18th century being overrun with ‘picturesque-hunters’.

Scandalous Sophia, back home in darkest Northumbria, was at a loose end and ready to take up any outrageous and fashionable activity. Amateur theatricals, yes; garden parties, those as well. And this exciting new pursuit of – ummm – going for a walk and looking at some scenery? Sophia Anne became an enthusiastic early adopter of the all-new, achingly trendy art of landscape appreciation. In her portrait at the top of this post, once you’ve stopped staring at the sensational ‘Le Pouf’ hairdo, you’ll notice the device called the Claude glass. You hold up this special lens so as to turn the surroundings into a tiny tinted and framed image as painted by Poussin. When using the slightly different one called the landscape mirror, you actually needed to turn around and stand with your back to the view to be admired, just like with a selfie stick.

If the National Trust is right in dating the portrait to around 1775, before either of her marriages, then Sophia was actually seven years ahead of Mr Gilpin’s book. That said, the hairstyle was inaugurated by the Duchess of Chartres in April 1774. If you want to get ahead, get a hairpiece: but was Sophia Anne really in on it in the very same season as Marie Antoinette?

Poor wild-child Sophia died in her late 30s, leaving debts of nearly £100 (at least £12,000 today6) which she’d run up maintaining her opium habit.

Ensign Jadis headed off to Nova Scotia. Their son Henry was raised at Seaton Delaval by his grandmother. Henry seems to have kept up the family’s traditions and its connection with the navy: in 1805 Captain Gardner of the 74-gun frigate HMS Hero obtained a judgement against him for criminal conversation with his (Capt. Gardner’s) wife Maria while he (Captain Gardner) was away leading the vanguard at the Battle of Cape Finisterre. Henry married Maria and lived on into the 1880s, to become an ancestor of fairly famous actress Frances de la Tour (Madame Maxine in ‘Harry Potter’).

With Sophia’s generation, the family’s male line died out as well. John, her only brother, had always been delicate in his health; he died in 1775, aged only 19, after being kicked in the groin by a laundry maid he was trying to seduce.

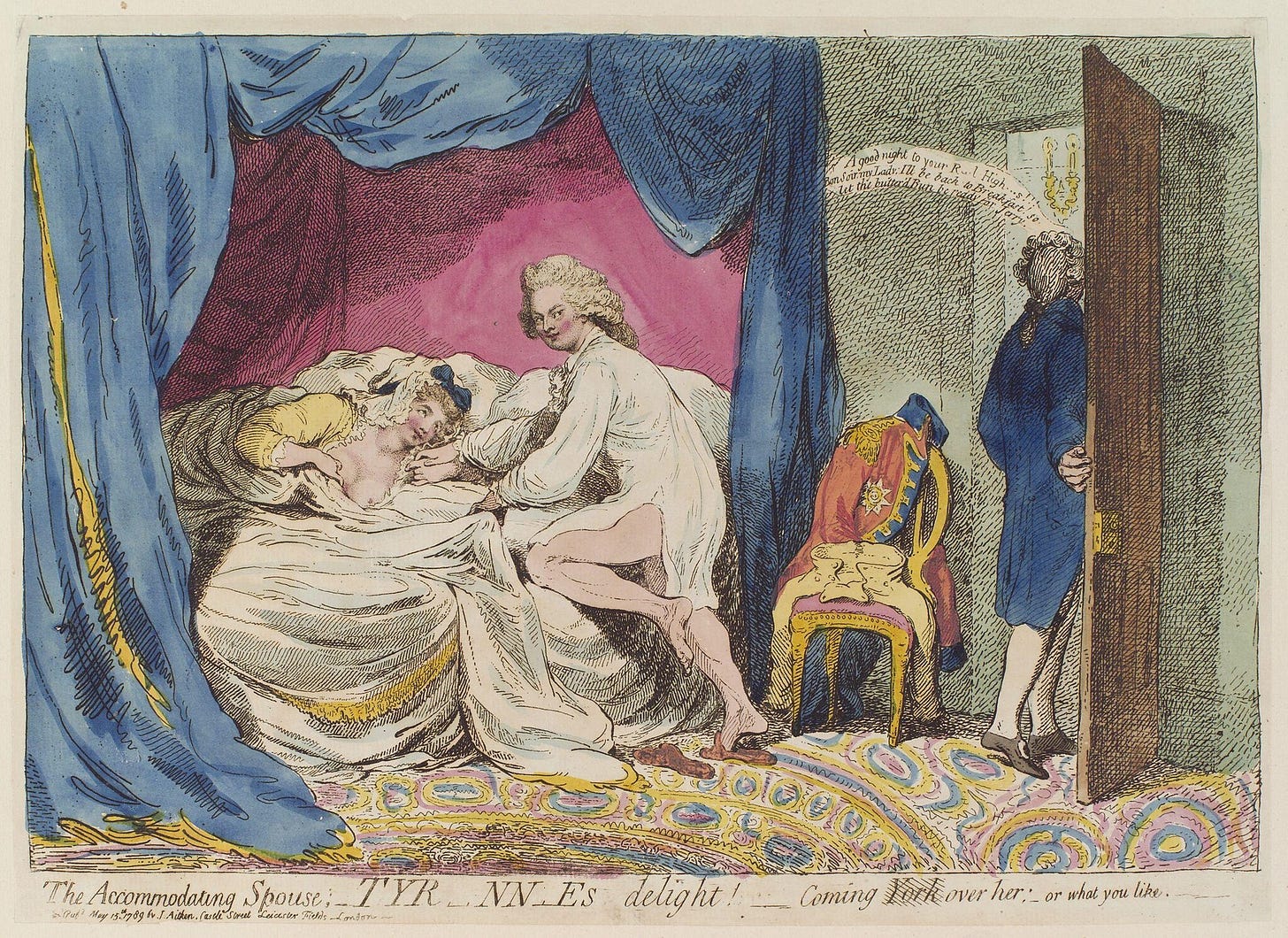

Meanwhile Sophia’s youngest sister Sarah Hussey Delaval, the one who’d married Lord Tyrconnel, became famous for her affair with Frederick Duke of York, second son of King George III. Lord Tyrconnel being the accommodating fellow who’d refrained from duelling with Sophia’s husband Ensign Jadis.

“Good night your Royal Highness!!!” says His Lordship (departing right): “Bonsoir my Lady: I'll be back to breakfast! so let this butter’d Bun be reddy for Jerry.” ‘Buttered bun’ (according to Green’s Dictionary of Slang) is ‘a woman who has had intercourse with one man and is about to repeat this immediately with a new partner’.

So unlike ‘Sophia’, meaning wisdom, Sarah Hussey did live up to her given name …7

In ‘Persuasion’, the near-bankrupt Sir Walter Elliot is reduced to renting out his country pile to Admiral Croft. The way naval officers could become inappropriately wealthy and move in on the aristocracy is a plot mechanism in Austen’s book.

Seaton Delaval Hall, north of Whitley Bay in Northumberland, is now managed by the National Trust.

Actually, one source says he fell of his horse too.

Sir Frances Blake Delaval, where do I start? Gambler, serial adulterer, amateur actor, corrupt politician, fortune hunter and first man ashore in the 1758 attack on St Malo.

The rent on Sophia and John’s London town house was £38 a year. She owed her drug dealer two and a half times that.

Thanks to Helen Smith, National Trust Collections Manager at Seaton Delaval, who supplied some extra Sophia info and pointed me at the book “The Delavals” by Martin Green. I did get a bit carried away researching Sophia and her family: in fairness, Ms Smith suggests that Sophia’s Claude glass is nothing but a fashionable accoutrement supplied by Mr Alcock the painter.

This was so enjoyable! Now want to know*much* more about Sophia who is splendid. (Also made me laugh - loved your description of WG...)

Sadly, there's very little more to know about Sophia. At least by way of information that's publicly available. William Gilpin - a pretty silly person who nevertheless changed the world a little, and for the better. Hope for all us slightly silly people...