The 18th Century Art of Landscape Appreciation

The strange craze for looking at England in a distorting mirror, backwards. [1400 words: 6 mins

It all began with the Grand Tour. That was the way of getting your aristocratic adolescent out of your house, hall, mansion or palace; maybe even improve his mind a bit. And above all get his disreputable adolescent behaviour away onto the other side of the English Channel. With luck he’d come back a bit more mature and even somewhat cultured up, ready to grieve at Daddy’s deathbed and start running the estate.

To get to Italy the young dukes and their tutors had to pass through the Alps: and despite the wolves and the frightful precipices, some of them (notably a chap called Horace Walpole) found they quite liked that bit of the trip. Mountains – maybe there was some point to them after all.

But the rising upper-middle class couldn’t afford the coach ride all the way to Rome. And then the Napoleonic War broke out, and nobody could go to Italy anyway. Staycation time, and the discovery, or invention, of the English Lake District.

Salvator Rosa ‘Bandits on a Rocky Coast’ c1660, Met Museum New York

When you went on your Grand Tour, a big part of the point was the special souvenirs. The landscape paintings by that achingly fashionable fellow Claude Lorrain and his pal Nicholas Poussin, not to mention Salvator Rosa. Salvator’s ones were especially thrilling because of featuring some decorative bandits lurking among the boulders.

England didn’t have any Italianate painters. But we did have the landscapes. And so came the latest craze of the 1780s: a very particular habit of trying to look at the Lake District exactly as if it was a 17th-century Italian painting.

The delicate touches of Claude, verified on Coniston lake, to the noble scenes of Poussin, exhibited on Windermere-water, and from these, to the stupendous romantic ideas of Salvator Rosa, realized on the lake of Derwent.1

Derwent Water: pretty as a picture, but sadly lacking in bandits. Henry Gastineau, etching/engraving by William Le Petit, early 19th century

So the strange craze for pretending England was actually an oil-painting by Claude Lorrain: this was something the world (or rather, upper-middle-class England) was waiting for. But it was actually invented by a vicar from Hampshire called William Gilpin. And quite quickly, it led to Lakeland, the Peak District, and other Instagram hotspots of the late 18th century being overrun with ‘picturesque-hunters’, armed with a device called the Claude glass or a different one called the landscape mirror. Standing with your back to the view to be admired, you held up this curved, tinted mirror so as to turn it into a framed image as painted by Poussin.

Sophia Anne Delaval deploys the Claude Glass, c 1775 (National Trust, Seaton Delaval, attributed to Edward Alcock). Sophia, daughter of one of the National Trust’s stately homes in Northumberland, returned from her Grand Tour pregnant and sort-of-married to a gentleman she’d left behind in Bordeaux.2

Absurd? Well, of course. As we now know, the real reason for turning your back to the landscape is to capture it with your selfie stick. But it did lead them to looking at Lakeland with greater intensity than 99% of us fellwalkers of today.

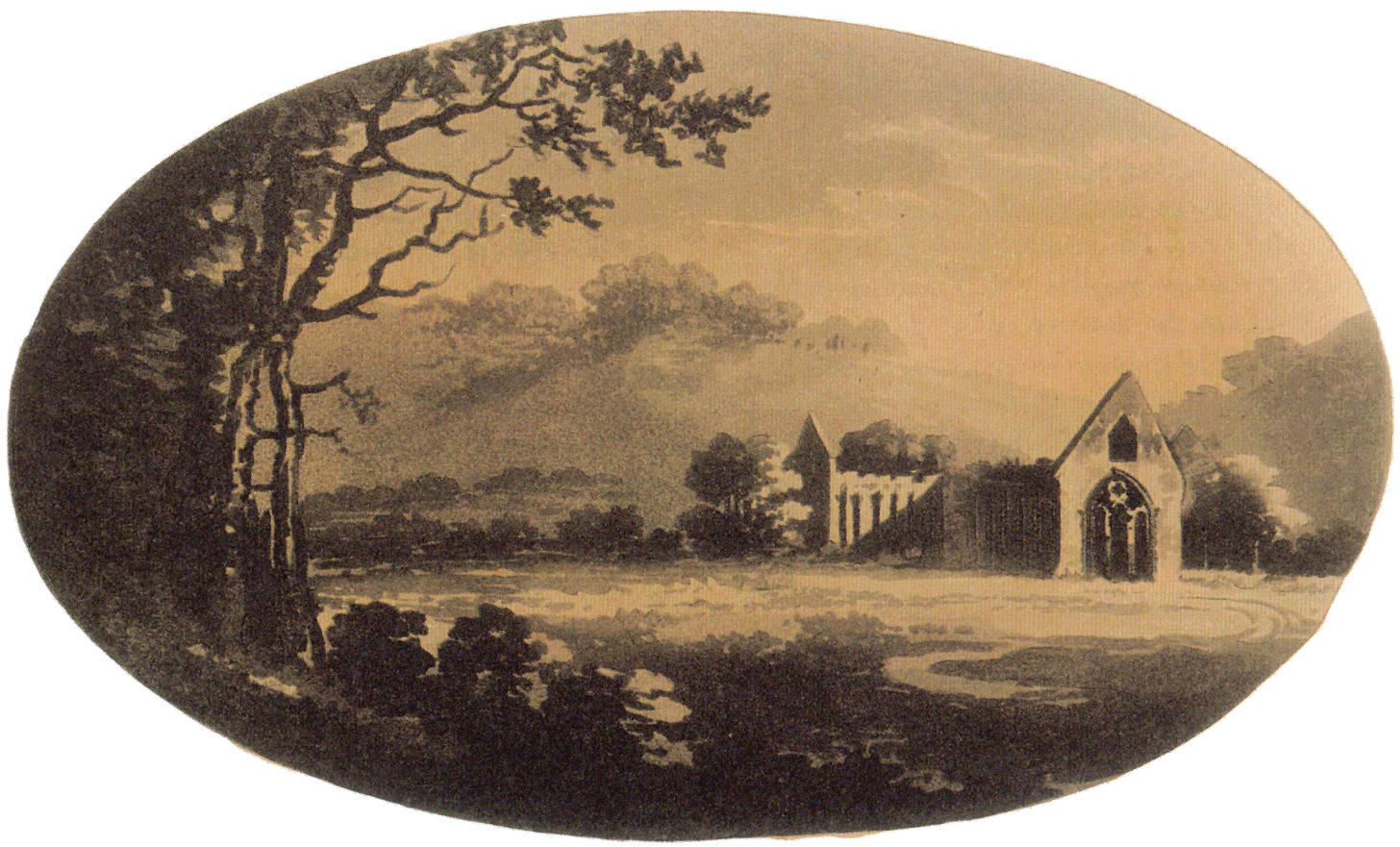

Gilpin’s first Picturesque Guide was to the River Wye, a popular tour of the time – even Admiral Nelson went for the scenic river cruise. And here, the celebrated Tintern Abbey comes in for particular criticism. It’s just not sufficiently ruined. Mr Gilpin even suggests a sledgehammer:

Though the parts are beautiful, the whole is ill shaped. No ruins of the tower are left, which might give form and contrast to the buttresses and walls. Instead of this a number of gable ends hurt the eye with their regularity, and disgust it by the vulgarity of their shape. A mallet judiciously used (but who durst use it?) might be of service in fracturing some of them, particularly those of the cross-aisles, which are both disagreeable in themselves, and confound the perspective.

The disgusting and vulgar gable-ends of Tintern Abbey: acquatint by William Gilpin from ‘Observations on the River Wye and Several Parts of South Wales, &c. Relative Chiefly to Picturesque Beauty Made in the Summer of the Year 1770’

Two years later William was at it again, up in the Lake Country. Where the shape of Saddleback, the hill now known as Blencathra, was found to be all wrong.

In the mean time, with all this magnificence and beauty, it cannot be supposed, that every scene, which these countries present, is correctly picturesque. In such immense bodies of rough-hewn matter, many irregularities, and even many deformities, must exist, which a practised eye would wish to correct….

Mountains therefore rising in regular, mathematical lines, or in whimsical, grotesque shapes, are displeasing. Thus a mountain in Cumberland, which from it’s peculiar appearance in some situations, takes the name of Saddleback, forms disagreeable lines. And thus many of the pointed summits of the Alps are objects rather of singularity than of beauty.3

William Gilpin’s selection of misshapen mountains in need of correction

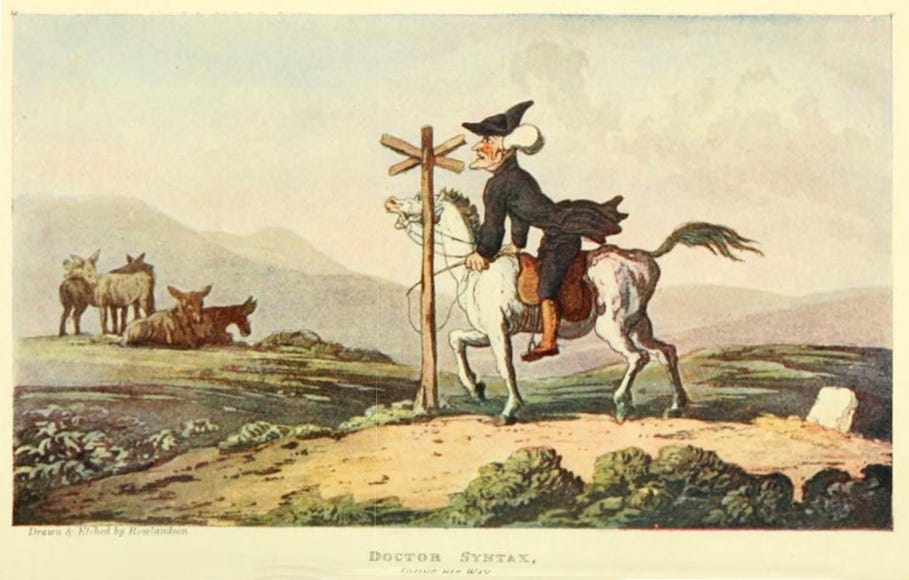

The more extreme a cult activity, the sooner it’s going to be over (Tamagotchi electronic pets, anybody? Ten years from now, will anybody still be doing the standup paddleboard?) And the poor picturesque-hunters were being satirised right from the beginning. The ‘Tour of Dr Syntax’ of 1812 [warning: very long] caricatures William Gilpin, lost on the moors with his horse Grizzle, finding a signpost so old and weatherworn that it’s lost its lettering. All the better for that: useless for showing the way, but excellent for a sketch.

Dr Syntax hand-coloured etching by Thomas Rowlandson, from ‘The Tour of Dr Syntax in Search of the Pictureseque’ by William Combe, 1812

There’s something picturesque about it;

‘Tis rude and rough, without a gloss

And is well covered o’er with moss;

And I’ve a right – (who dares deny it?)

To place yon group of asses by it.

Dr Syntax steps back to frame a nicely knocked-about ruin

And in 1803, in ‘Northanger Abbey’, Jane Austen is affectionately mocking the book’s hero, Mr Tilney, as he instructs Catherine in the techniques of looking at a landscape:

The little which [Catherine] could understand, however, appeared to contradict the very few notions she had entertained on the matter before. It seemed as if a good view were no longer to be taken from the top of an high hill, and that a clear blue sky was no longer a proof of a fine day…

She was heartily ashamed of her ignorance… A lecture on the picturesque immediately followed, in which [Mr Tilney’s] instructions were so clear that she soon began to see beauty in everything admired by him, and her attention was so earnest that he became perfectly satisfied of her having a great deal of natural taste. He talked of foregrounds, distances, and second distances – side-screens and perspectives – lights and shades; – and Catherine was so hopeful a scholar that when they gained the top of Beechen Cliff, she voluntarily rejected the whole city of Bath as unworthy to make part of a landscape.4

As a very young man, landscape enthusiast William Wordsworth was a follower of Gilpin’s picturesque principles. But by 1796, when he made his own walking tour up the River Wye, he’d already moved on. Now he admired more the innocent eye of his sister Dorothy: seeking those moments of landscape rapture, far beyond the mallet-wielding rulebook of William Gilpin:

… that serene and blessed mood,

In which the affections gently lead us on,—

Until, the breath of this corporeal frame

And even the motion of our human blood

Almost suspended, we are laid asleep

In body, and become a living soul:

While with an eye made quiet by the power

Of harmony, and the deep power of joy,

We see into the life of things.5

Today, it’s an almost automatic assumption: the reason for going up a hill is the view from the top. So that our friends and family find it odd when some of us still go up them when the cloud’s down. But this isn’t something that’s deeply embedded in the human condition. Taking a trip to see some scenery – and to catch it in a Claude glass or a camera: it’s an idea that’s only been around since Mr Gilpin in 1782.

Thomas West ‘Guide to the Lakes’ 1778

According to the National Trust’s curator, Sophie Anne, daughter of Lord Delaval, took her 18th century behaviour seriously. Sophie returned from her Grand Tour ‘sort-of-married’ to Mr Henry Devereux, whom she had left behind in Bordeaux. After the birth of her son she headed back to France for a second Grand Tour, acquiring (just like Lydia Bennet in ‘Pride and Prejudice’) a young army officer, ensign John Jadis, as her second ‘sort-of-husband’. As in Jane Austen’s book, Lord Delaval hastily arranges a proper English wedding and an annual payment of £100 to Ensign Jadis.

Jane Austen doesn’t give us the future life of Lydia and Mr Wickham; Sophie Anne’s outcome could supply a hint. After a duel with Sophie’s brother Lord Tyrconnel (actually just a challenge, nobody got killed) Jadis separates from his wife. Sophie then lives with her parents in their stately home, presumably diverted by the occasional tour of the Lake Country. She dies in her late 30s leaving debts of nearly £100 (at least £12,000 today) which the National Trust suggests may have been for maintaining her opium habit.

Observations, relative chiefly to Picturesque Beauty, Made in the Year 1772, On several Parts of England; particularly the Mountains and Lakes of Cumberland and Westmoreland

Jane Austen ‘Northanger Abbey’ (written 1806, set in the late 1790s, published 1817) Chapter 14

Good stuff once more.

"Pretending England was actually an oil-painting by Claude Lorrain": does this have a counterpart in the prevalence of over-processed and -filtered digital photos, with the new lure of further 'enhancement' thanks to so-called 'AI'?