Ladies of Lakeland

Not all of the first fellwalkers were beardie blokes. Let’s celebrate Dorothy, co-inventor of English Romanticism; her friend Mary; Mary’s maid Agnes; and the astonishing Miss Smith. [1200 words, 5min

The first walkers up onto the Lakeland fells were shepherds and small farmers from the surrounding valleys. But the first ones up there just for fun, and writing about it afterwards, were the Romantic poets Samuel Taylor Coleridge with William and Dorothy Wordsworth. And Dorothy’s example meant that, right from the start, fellwalking was never going to be a boys-only sport.

Dorothy’s hiking habit is well recorded. There was the three-day outing around Exmoor when working up Coleridge’s ‘Ancient Mariner’; the midwinter walk across the Pennines to Grasmere in 1799; the innumerable trips around Rydal Water to collect the post from Clappersgate; the stroll over to Ullswater to behold those daffodils. Actual mountaintops? Not so many, but her brother did write her up on one of them:

Inmate of a mountain-dwelling,

Thou hast clomb aloft, and gazed

From the watch-towers of Helvellyn;

Awed, delighted, and amazed!To — on her first ascent to Helvellyn, 18161

Having referred to her as “—”, William’s next reference to Dorothy’s peakbagging was even more discreet. In his Guide to the Lakes, he attributed her ascent of Scafell Pike to none other than – himself. In later editions that was updated to “a Friend” (of unspecified gender).

Dorothy’s account of her hillwalk is here: and I’m writing about it in the March/April issue of Lakeland Walker magazine.

Scafell Pike from Ill Crag. Dorothy Wordsworth reached the summit from Esk Hause “after much toil, though without difficulty”.

By 1818, when Dorothy was summiting Scafell Pike, other women were already taking to the fells. For a start, there were her companions on that walk up Scafell Pike. Indeed, the reason they were heading to Esk Hause at all was because Mary Barker and her maid Agnes had been there already. A few months before, the two women had crossed it in the course of an ambitious three-day trip over into Wasdale and Eskdale.

Mary Barker (born 1774) was a woman of fairly independent means, who moved to Rosthwaite in Borrowdale for the sake of the romantical landscapes. She soon made friends with Poet Lauriate Robert Southey of Keswick, and through him with Coleridge and the Wordsworths. She was a poet, painter, and also a novelist: A Welsh Story is in the fashionable genre of ‘Romantic Welsh Gothick’. (Fashionable in the 1790s, that is.)

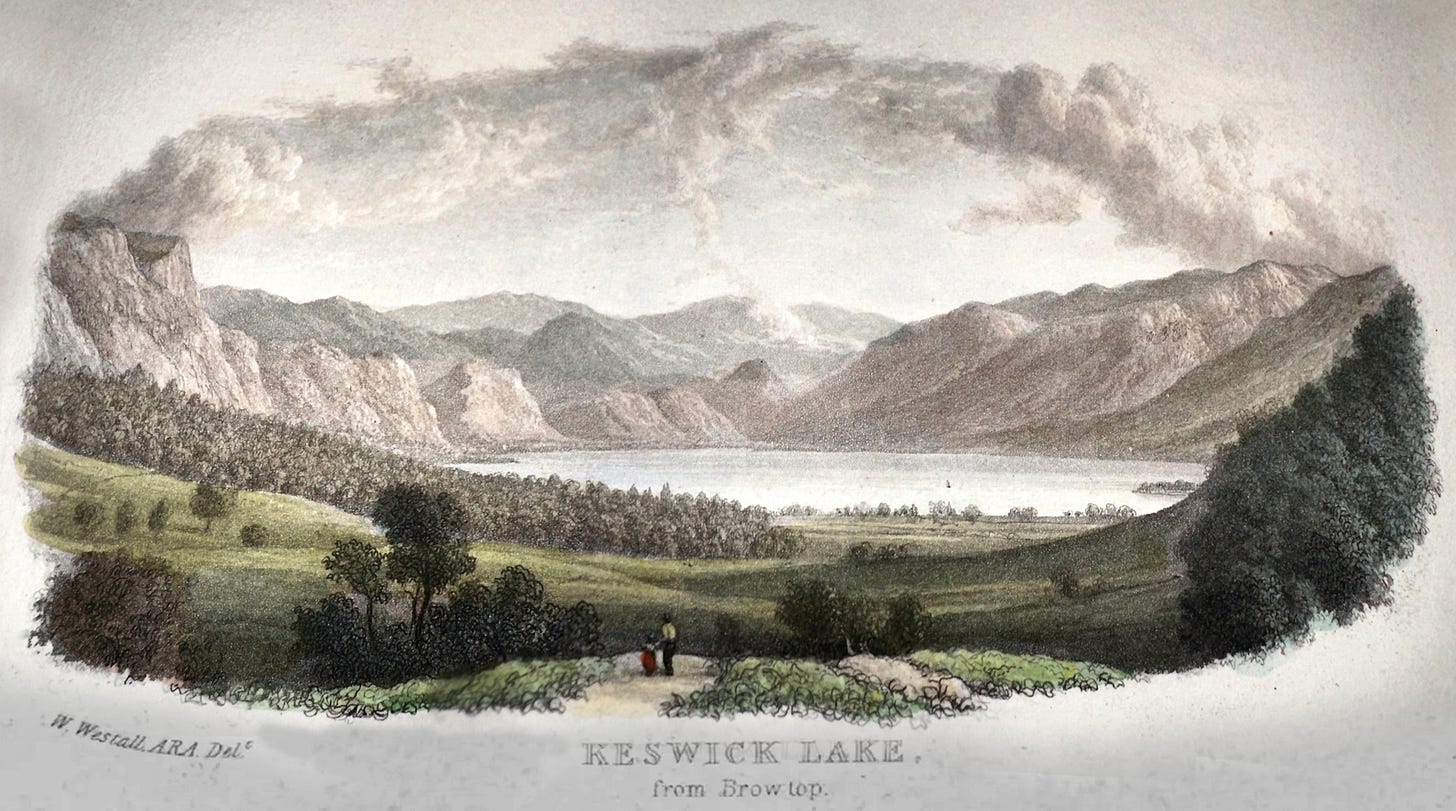

Derwent Water by William Westall, another member of the Robert Southey set, and there’s a suggestion in Southey’s letters of a romantic attachment to the adventurous Miss Barker.

Financially, Miss Barker wasn’t as independent as she thought. She’d overstretched herself with the fine Gothick mansion at Rosthwaite (it’s now the Scafell Hotel). She went bankrupt, and fled to France to escape her debts. But as a fellwalker, she was a fully independent sort. She and Agnes successfully crossed Sty Head to Wasdale without a guide – it was a well used path even back in 1818.

For Day Two they made their way in a farm cart round into Eskdale. The Wool Pack offered them a mixed-sex dormitory, which they declined; the inn at Boot turned them away altogether as disreputable fellwalkers: “We have no accommodation for such as you!”

Having found somewhere to stay, the next day they hired a guide to take them over the wild and untrodden pass of “Ash Course” or Esk Hause. But somewhere in upper Eskdale, their guide abandoned them. “It's no use my ganging any farder wi' ye, for I dunnon ken the way any farder mysell.”

Upper Eskdale: Esk Hause is the high pass at top centre.

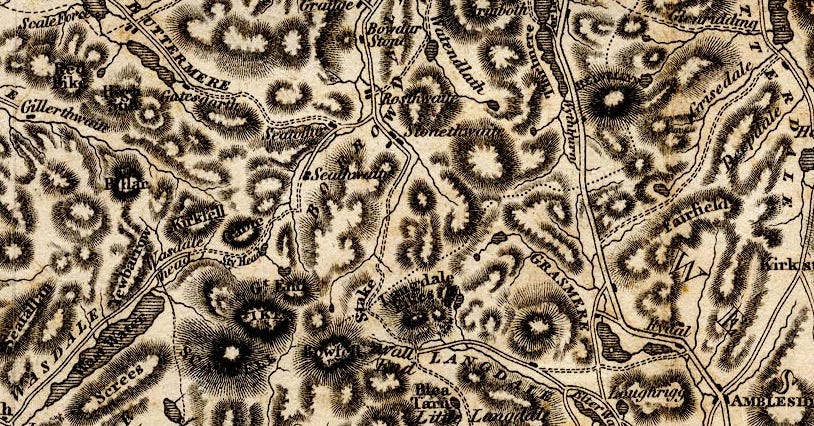

The two women made it up there anyway, and Miss Barker was so taken with the views in the evening light that Agnes had to remind her that any sunset, however splendid, will necessarily be followed by nightfall. And they still had to find the way down to Seathwaite. Which, with the help of Mr Jonathan Otley’s new map, they managed to do.

Borrowdale to Scafell Pikes, as shown on Jonathan Otley’s fine new map of 1818

It was Mr Otley himself, by way of promoting his own map, who recorded their three-day journey in the ‘Kendal Mercury’. He also describes how, a few years later, a mixed party following Dorothy’s letter out of WW’s guidebook made the same journey up from Borrowdale. At Esk Hause one keen and confident lady wanted to go a bit further on her own. Unfortunately she met a shepherd, and asked him the best way down to Seathwaite. Even more unfortunately, she pronounced it ‘Seathet’ rather than ‘Seawait’, and so was directed to Seathwaite in the Duddon Valley. Thus becoming the first (but not the last) recorded person to descend the wrong valley out of Esk Hause.

Esk Hause, looking towards Scafell Pike. Borrowdale down right, Eskdale down left.

Recruiting a guide from Cockley Beck, the lost lady returned to Rosthwaite in the dark by way of Wrynose, Blea Tarn, Langdale Head and the Stake Pass. A total for her day of 38km with 1550m of ascent.

Linguist and fellwalker Miss Elizabeth Smith of Coniston

These are just the ones whose walks happened to get written up. We know for sure that they weren’t the only ones, or even the first. Thomas Wilkinson’s Tours to the British Mountains (1824) mentions Mrs Smith of Coniston and her two daughters, right at the start of the century, heading up Helvellyn without a guide, and in winter conditions as well.

Miss Elizabeth Smith had settled with her mother and sister at Coniston in 1801. Daughter of a bankrupt banker who became an army officer, Miss Smith (readers of Jane Austen will be aware that as the eldest daughter she doesn’t require a first name) was taught French and a little Italian by her governess. But she went on to teach herself Italian, Spanish, Garman and Arabic. Oh, and also Persian, Latin, irish and Hebrew. Along with a smattering of Welsh, Chinese, some African dialects, and Icelandic.

In the spring of 1801, at the age of 24, she attempted a solo and guideless ascent of Aira Force, trusting to the hill skills from her earlier outings in Wales and the North Country. She headed up into the ‘aerial dungeon’ with a foldable sketching-stool and ‘some purpose of sketching, not the whole scene, but some picturesque feature of it’. She became cragfast among the rocks, but was shown the way to safety by ‘a lady in a white muslin morning-robe, such as were then universally worn by young ladies until dinner-time,’ who on closer inspection turned out to be an apparition of her own sister.2

Aira Force: serious scrambling in pursuit of the picturesque. In 1801 the bridges weren’t built yet.

Miss Elizabeth won’t have been inspired by Dorothy Wordsworth, who at the time was only just settling in to Dove Cottage. Instead, the sketching-stool indentifies her as a ‘Laker’ and a ‘Picturesque-hunter’, armed with the instructional manuals of William Gilpin. (My previous About Mountains post about picturesque-hunters is here.) But her adventurous expeditions mark her as a full-on fellwalker. Sadly, though, this promising life was cut short. On one of her walks she sat too long in the early morning dew and caught what seems to have been pneumonia. She asked to be brought out of the house to an open tent, where she spent her last days looking across the lake to Coniston Old Man.

After their ascents of Helvellyn, where next for the ladies of Lakeland? William W has some suggestions in the poem already quoted:

Maiden! now take flight;—inherit

Alps or Andes—they are thine!

And why stop there? How about ‘the untrodden lunar mountains’ even?

The Moon, maybe not. But within a few years of Dorothy’s day on Scafell Pike, at least one woman was leaving the menfolk behind for trips to Europe’s greater ranges. I’ll be writing about Anne Lister later in this series.

Without this ghostly moment, Miss Smith’s adventurous outing wouldn’t even have been recorded. It’s in The Haunted Homes and Family Traditions of Great Britain (1897), where John Ingram directly quotes an account in an article that appeared in ‘News from the Invisible World’.

Examples of these women can be mentioned in the modern era, Mrs. Wanda Rutkowicz from Poland, who went further in that closed communist space where men considered it their right to climb mountains, or Mrs. Elizabeth Hargroves from England.

Hello Ronald, in the two articles I read about the history of women, one on the UK Climbing website and a recent post, it was very interesting to me. Women like Dorothy Wallister and Smith were great pioneers who were able to break the limits of the traditional societies of England and Wales and Scotland and 100 years ahead of time. be yourself