Ladies in the Alps

Climbing mountains in the 1820s: an obviously masculine activity? Well, maybe not… [1600 words 7min

Climbing mountains is an obviously masculine activity. Big ambitions, big legs, and a certain blindness to the possibility of ending up in an avalanche: these are attributes of people with penises. Except – in an age when women were excluded from all the professions, from the clubs of London, from Parliament and even from owning property and being allowed to vote – some of them were already up there in the Alps.

I mean to say. Climbing up a big pointy thing in order to show off your muscles, your courage and your contempt for death: what could be more gender specific than that?

But no.

Ann Radcliffe visits the Rhineland, 1794

Mrs Radcliffe is mostly famous for her Gothic novels: especially ‘Mysteries of Udolpho’ as affectionately satirised by Jane Austen.1 But she was also one of the first out there exploring the crags of the Rhineland.

This mountain towers, the majestic sentinel of the river over which it aspires, in vast masses of rock, varied with rich tuftings of dwarf-wood, and bearing on its narrow peak the remains of a castle, whose walls seem to rise in a line with the perpendicular precipice, on which they stand, and, when viewed from the opposite bank, appear little more than a rugged cabin. The eye aches in attempting to scale this rock; but the sublimity of its height and the grandeur of its intermingled cliffs and woods gratify the warmest wish of fancy.

Marie Paradis 1808

Just looking at the mountains made Mrs Radcliffe’s eyes ache. But in order to ache all over, you really need to climb the things. Which Marie Paradis, an 18-year-old servant girl from Chamonix, duly did on Mont Blanc in 1808.

One day the guides said to me, “We are going up there, come with us. Travellers will come and see you afterwards and give you presents.” … When I reached the Grand Plateau I could not walk any longer. I felt very ill, and I lay down on the snow. I panted like a chicken in the heat. They held me up by my arms on each side and dragged me along. But at the Rochers-Rouge I could get no further, and I said to them: “Chuck me into a crevasse and go on yourselves.” (“Ficha mé din una crevasse et alla ô vo vodra!”)

“You must go to the top,” answered the guides. They seized hold of me, they dragged me, they pushed me, they carried me, and at last we arrived. Once at the summit, I could see nothing clearly, I could not breathe; I could not speak.

Marie’s own account, translated by later Alpinist Mrs Aubrey Le Blond (True Tales of Mountain Adventures 1903)

She was given little credit for her ascent, and there were two good reasons for that. Firstly she was a woman; secondly she was working class. But also, her own account has her, in effect, carried up the mountain by her two guides. We note though that it isn’t actually possible for two human beings to carry a third one up steep snowslopes at an altitude over 4500m.

Anyway, being ‘Marie of Mont Blanc’ did give her financial security for the rest of her life.

Meanwhile, over in England

Dorothy Wordsworth, her friend Mary Barker and the astonishing Miss Elizabeth Smith were making sure that fellwalking was never going to be just for the fellas. I’ve written already about these Ladies of Lakeland.

And then, in July of 1814, Mary Godwin, with her boyfriend Percy Bysshe Shelley and her stepsister Claire Claremont, fixed on a plan “eccentric enough, but which, from its romance, was very pleasing to us. In England we could not have put it into execution without sustaining continual insult and impertinence… We resolved to walk through France.” Aiming in particular for “the glaciers, and the lakes, and the forests, and the fountains of the mighty Alps.”

This was an all-new thing to do: Romantic Travel. The aim wasn't to gather souvenirs in the shape of Renaissance paintings to hang in your stately home. The aim was to experience experiences. And not necessarily pleasant ones…

The fun started straight away. To save time, they set out across the Channel in a small boat. Through the sunset and the moonlight and a gale and a thunderstorm that almost capsized the boat, arriving in France at sunrise. How Romantic is that?

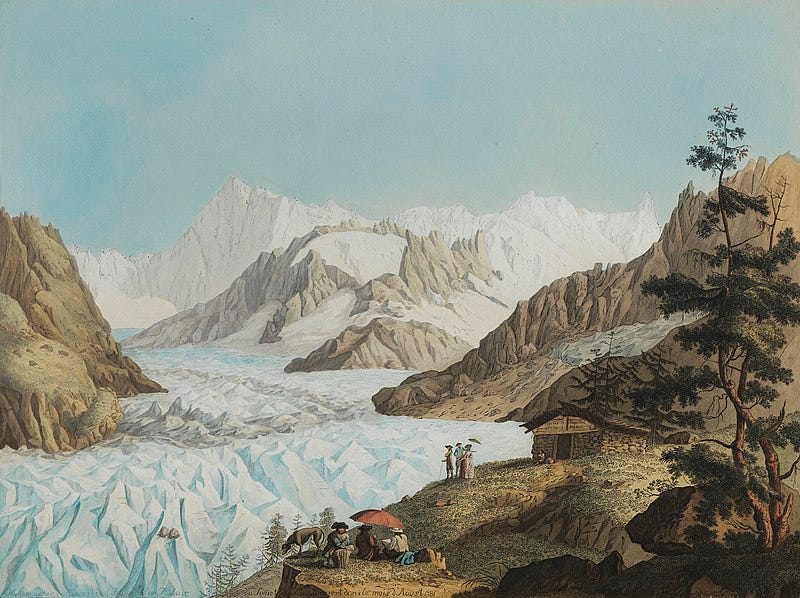

Two years later Mary and Percy came again, accompanied by Lord Byron and a person called Polidori, this time making it to Geneva and down to Chamonix. The two trips combined into the ‘History of a Six Weeks Tour’: by the time it came out Mary and Percy were married, so she's credited as Mary Shelley. And the Mer de Glace, as seen from Montanvert, makes it into Chapter X of her great science-fiction novel ‘Frankenstein’.

I remained in a recess of the rock, gazing on this wonderful and stupendous scene. The sea, or rather the vast river of ice, wound among its dependent mountains, whose aerial summits hung over its recesses. Their icy and glittering peaks shone in the sunlight over the clouds. My heart, which was before sorrowful, now swelled with something like joy; I exclaimed—“Wandering spirits, if indeed ye wander, and do not rest in your narrow beds, allow me this faint happiness, or take me, as your companion, away from the joys of life.”

Anne Lister

Miss Anne Lister made it up to Montanvert as well. But she also went further and higher…

Anne Lister, nicknamed ‘Gentleman Jack’, is mostly celebrated as an out and proud lesbian, and her intimate diaries, now preserved by West Yorkshire Archive Service in Calderdale, give valued insight into sexuality in early 19th century England. All of which has somewhat obscured her mountaineering achievements.

Her walking tour in the Alps, with her appropriately named lover and later wife Ann Walker, included crossings of the Col Ferret at 2490m (high point of today’s Tour du Mont Blanc), Le Brévent (2525m), the Mer de Glace, the Great St Bernard and the Puy de Dôme. She had her eye on Mont Blanc, but never got the weather window.

I love, & only love, the fairer sex & thus beloved by them in turn, my heart revolts from any other love than theirs.

Anne Lister – journals

But her most striking climb was the first ever recorded female first ascent of anything at all. That being Vignemale (3298m), the high-point of the French Pyrenees, in 1838.

Equipped with "2 pair gloves and 1 pair handkerchief and tooth brush, soap, comb, needle and thread, and stiletto [dagger] all in one parcel tied up in a sheet of large whity brown paper" with 100 francs hidden in her stocking, as well a bâton ferré (a simple walking pole with iron tip but no spike) and the crampons used 8 years before on her ascent of Mont-Perdu (Monte Perdido, 3355m). “Yet,” she wrote in her diary, “I was lightly equipped and my heart was light.”

After a short and sleepless night, she leaves the high-level hovel (Saousse Dabat) at 3 am with her three local guides. Her travel diary records her on horseback until 5.20am, then on foot; “climbed the chimney” before cramponning up the first snowslope.

Half an hour’s rest at 11.15, vomiting briefly; then off again to arrive on the summit at 1pm. Back at the Saoussats Dabats hut just after 8pm. A few hours rest waiting for the moon to rise, then descent to Gavarnie by moonlight.

The route she used is now known as the voie Moskowa to the Col Lady Lyster (sic). I don’t know it myself, but in the 1988 Pyrenees guide it’s graded AD– : “There is one short section of [rock-climbing grade] II immediately followed by a chimney at III. This section is about 50 metres long and the chimney is described as poor rock and rope advisable. (Anne’s party didn’t carry a rope.) Elsewhere the route is graded slightly lower, as PD III. PD (peu difficile) is the second easiest Alpine grade; rock grade III is equivalent to UK Moderate or Difficult.

Three days later, one of her three guides (Henri Cazaux, (the original discoverer of the route) escorted the Prince de la Moskowa, pretending to him that Anne hadn’t already made it. The treacherous guide even sent a porter ahead to remove the bottle with Anne’s name in it from the summit cairn. The Prince (his bizarre title had been granted by Napoleon to his father, the successful general Marshal Ney) had trouble believing that he’d been pipped to the peak by a Lady, and was very unprincely about acknowledging her claim. Despite notarised certificates from her three guides (the traitor eventually recanted) it took several decades for Anne to be recognised as the first ‘amateur’ ascent. (Apparently the previous ascent by her local guide didn’t count.)

Anne never made it up Mont Blanc; but in 1838, Henriette d’Angerville made its second penis-free ascent, popping a bottle of champagne at the top. Most of the fine wine will have escaped into the atmosphere. Just as well: altitude plus alcohol being a bad mix really.

Over the next 20 years, the Alps were taken over by English: members of the Upper Middle Class and the Alpine Club, climbing big, serious stuff like the Matterhorn. But, in the 1870s and 80s – maybe it’s because mountaineers are oddballs already – it does seem that women were excluded somewhat less than they were from other male-dominated activities.

And so a later post will celebrate the Pigeon Sisters Anna and Ellen; Mrs Mary Mummery; and most notably the lively and talented Miss Lily Bristow of South London.

In ‘Northanger Abbey’. Its heroine, Catherine Morland, is a reader of Mrs Radcliffe (so is Mr Tilney, for that matter). But the book itself is a parody of Radcliffe plotlines.

Not only in the Alps, but in America, Ladies on Mt. Rainier's glaciers early in the 20th C.

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/adventure/article/140603-mount-rainier-history-pictures-photos-climbing-accident

What a delightful post!