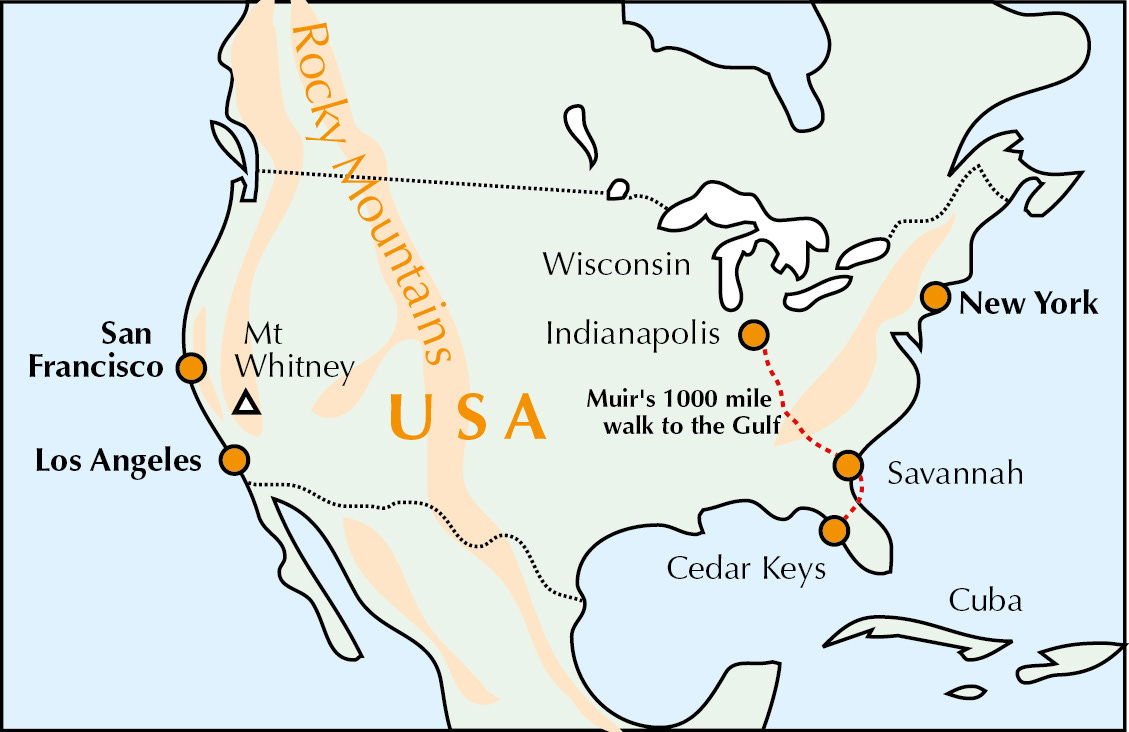

John Muir's 1000-mile walk to Florida

John Muir walks across the eastern USA in 1867 [1800 words 8 mins

“In every walk with nature one receives far more than he seeks. The clearest way into the Universe is through a forest wilderness.”

On 2 Sept 1867, at the age of 29, John Muir abandoned normal life and became a wanderer. He walked from the northern USA through to the Gulf of Mexico, 1000 miles across a country still dangerous in the aftermath of the Civil War. He survived rattlesnakes, a dodgy river crossing and three attempted robberies, and caught both malaria and typhoid due to bivvying out in mosquito infested swamps.

In the US John Muir is revered as the founding father of the national parks. But here’s a brief backstory for Brits. Born in Dunbar, south of Edinburgh, John Muir sailed from Scotland aged eleven for the harsh life of a pioneer farmer in Wisconsin. On leaving the family home he became an engineer and mechanic, inventing among other things a tip-you-out-of-bed machine and a clockwork precursor of the Kindle book reader. However, a metal file that he was using struck him in the eye, and for several weeks he was blind and in great pain. This event served, rather like his own internally-sprung bed, as an abrupt wakeup call.

John Muir’s clockwork lectern with automated page-turn. Wisconsin Historical Museum. Excellent account of the device and its context from Wisconsin Historical Society

“My plan was simply to push on in a general southward direction (he carried a compass) by the wildest, leafiest, and least trodden way I could find, promising the greatest extent of virgin forest.” He’d told his mother that he “would not lie out of doors if I could possibly avoid it.” A promise he had no intention of keeping.

The walk account was compiled from his journal and published in 1916 after Muir’s death

He carried only a plant press and a small bag of belongings. He would walk around 25 miles, then beg or buy some overnight accommodation, or else sleep out in his clothes among the plantlife.

Kit list

As he crosses the remote Cumberland mountains, a fellow traveller offers to carry his bag – with the intention of rummaging through it to steal stuff. To save trouble, Muir lets him find out for himself that there’s nothing worth pinching. As well as the plant press carried on his back, the bag contains: comb, hairbrush, towel, soap, one change of underclothing, the poems of Robert Burns, Milton’s ‘Paradise Lost’, and a small New Testament.

Most of the eastern USA is still mixed forest and farmland; but his crossing of the Appalachians is trees all the time. The trip’s geographical high point, Waucheesi Mountain is at 3692ft on Sept 18th.

My tarp tent on the Mountains to the Sea Trail, North Carolina

I walked through these hills for four days1. By the end of the four days I’d seen roughly one million trees: and that was as many trees, and as much of the Appalachians, as I really wanted. But John Muir couldn’t get enough of it:

Such an ocean of wooded, waving, swelling mountain beauty and forest-clad hills, side by side in rows and groups, seemed to be enoying the rich sunshine and remaining motionless only because they were so eagerly absorbing it. All were united by curves and slopes of inimitable softness and beauty.2

The Taylor-Grady house on Prince Avenue, Athens, built for General Robert Taylor, Irish immigrant and plantation owner. [photographed for ‘About Mountains’ by Mark Hodges

Athens GA

Normally John Muir walked through towns with his head down, disappointed by the meagre plantlife of the pavements. Sorry, the sidewalks. But he was impressed by Athens, Georgia:

A remarkably beautiful and aristocratic town, containing many classic and magnificent mansions of wealthy planters, who formerly owned large negro-stocked plantations in the best cotton and sugar regions farther south. Unmistakable marks of culture and refinement, as well as wealth, were everywhere apparent. This is the most beautiful town I have seen on the journey, so far, and the only one in the South that I would like to revisit.

The negroes here have been well trained and are extremely polite. When they come in sight of a white man on the road, off go their hats, even at a distance of forty or fify yards, and they walk bare-headed until he is out of sight.

Clearly Muir here didn’t understand what he was seeing, or appreciate the realities of slavery – a freed slave showing insufficient respect to the white man being liable to be lynched.

Because, in general, JM at 29 was much more into trees and plantlife than people. Sept 29th: “Today I met a magnificent grass, ten or twelve feet in stature, with a superb panicle of glossy purple flowers.… It seems to be fully aware of its high rank, and waves with the grace and solemn majesty of a mountain pine.”

walk map from ‘Muir & More’, my book about Muir’s life and walks

Traces of war

Even the recent civil war, he sees first in terms of its damage to trees…

The traces of war are not only apparent on the broken fields, burnt fences, mills, and woods ruthlessly slaughtered, but also on the countenances of the people. A few years after a forest has been burned another generation of bright and happy trees arises, in purest freshest vigor; only the old trees, wholly or half dead, bear marks of the calamity. So with the people of this war-field. Happy, unscarred, and unclouded youth is growing up around the aged, half-consumed, and fallen parents, who bear in sad measure the ineffaceable marks of the farthest-reaching and most infernal of all civilized calamities.

On Oct 8th, after 35 walking days, he reaches the sea at Savannah. The distance so far is is 630 miles on Google maps – an average of 18 miles/day supposing he’d taken Google’s recommended walking route – his actual route will have been rather longer. His longest day, to Augusta GA on Sept 30th, he reckons at more than 40 miles.

If reading on email, and the email gets cut off, please hit ‘view in browser’ right up at the top

Graveyard days

At Savannah he’s expecting to collect money at the post office for the next stage of his journey. But it hasn’t arrived. So he spends a week bivvying in Bonaventure graveyard, slowly starving to death on 10 cents a day.

No longer covering his 20 miles, he has time to describe his sleeping quarters: “Almost any sensible person would choose to dwell here with the dead rather than with the lazy, disorderly living.”

All the avenue where I walked was in shadow, but an exposed tombstone frequently shone out in startling whiteness on either hand, and thickets of sparkleberry bushes gleamed like heaps of crystals. Not a breath of air moved the gray moss, and the great black arms of the trees met overhead and covered the avenue. But the canopy was fissured by many a netted seam and leafy-edged opening, through which the moonlight sifted in auroral rays, broidering the blackness in silvery light.

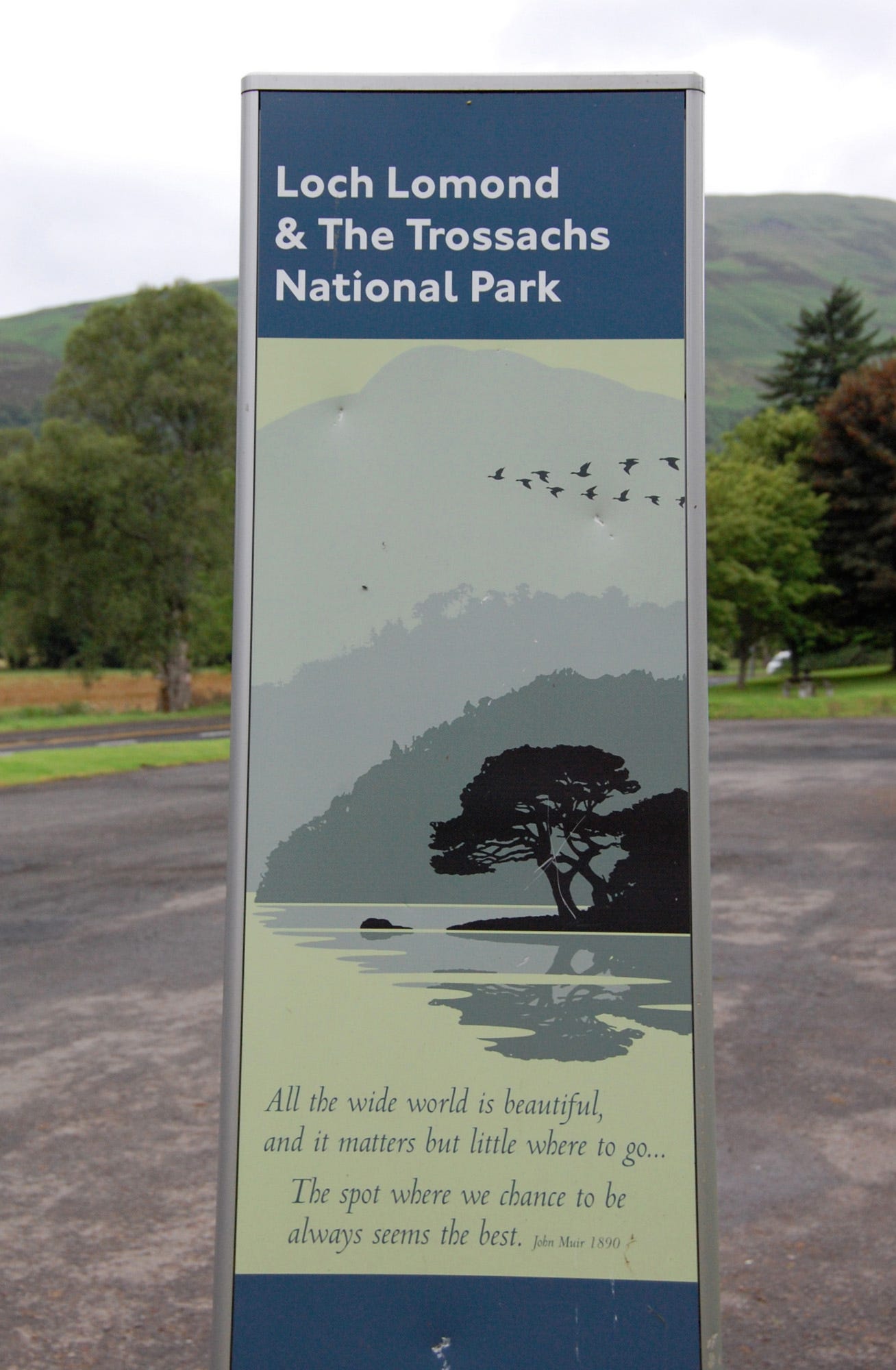

So yes, here’s the beginning of the exhuberant JM prose style. Today we may find it flowery. Okay, it’s derived from Thoreau and Emerson, but unlike those two Eastern Seabord philosophers, Muir also walked the walk. Anyway, it worked for his 19th century audience, and became his effective tool in his activism towards the founding of the American national park system. And the UK’s national parks, today, are happy to pluck his flowery sentences for their interpretation boards.

“All the wide world is beautiful, and it matters but little where to go… The spot where we chance to be always seems the best.” JM did pass through the future Lomond & Trossach national park on his way to founding the Yosemite, Sequoia, Mt. Rainier and Grand Canyon ones.

As soon as his money arrives, he’s off in a boat to Fernandina, Florida, which he reaches on 15th October. He buys some bread and: “without asking a single question, I make for the shady, gloomy groves.”

He finds the Florida swamps infested with alligators and dangerous human beings, without a single spot of dry ground to lie down on, while surrounded with utterly thrilling and surprising plantlife. In particular, those trees. “I have seen magnolias, tupelo, live-oak, Kentucky oak, tillandsia, long-leafed pine, palmetto, schrankia, and whole forests of strange trees…”

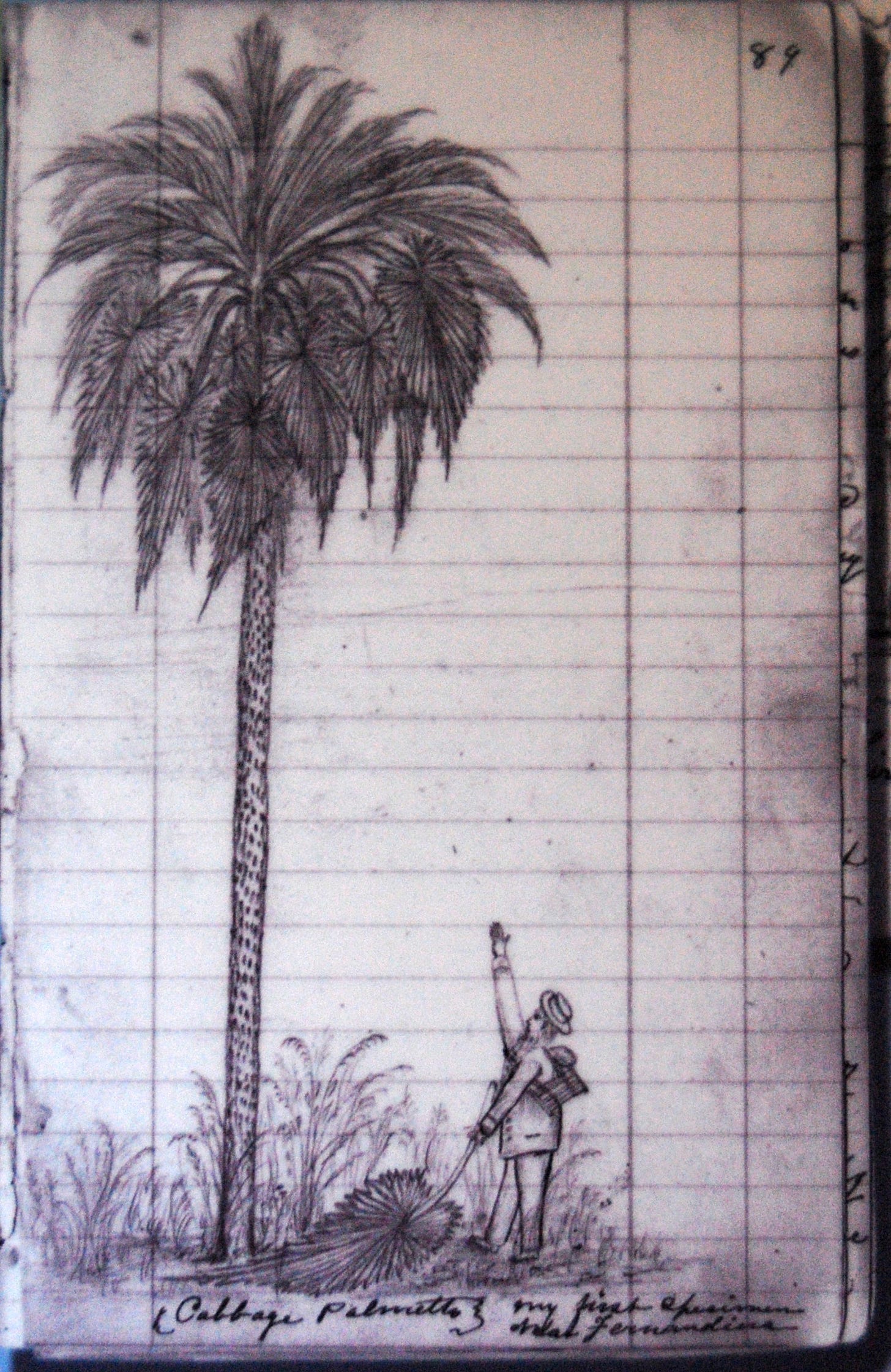

Lime Key, Florida. Sketch from John Muir’s Journal

Palmetto Tuesday

And on Tuesday October 15th3 he meets the finest tree so far:

This palm was indescribably impressive and told me grander things than I ever got from human priest…. Whether rocking and rustling in the wind or poised thoughtful and calm in the sunshine, it has a power of expression not excelled by any plant high or low that I have met in my whole walk thus far.

John Muir worshipping a Palmetto tree – from his journal, displayed at John Muir House, Dunbar, Scotland

While still using the language of conventional religion, this is a thinly disguised worship of trees. “Glad to leave these ecclesiastical fires and blunders, I joyfully return to the immortal truth and immortal beauty of Nature.”

Muir reaches the Gulf of Mexico on October 23rd 1867. Here he falls seriously ill (those mosquitoes! That stagnant drinking water!) and lies convalescing at a friendly sawmill until January. Then he picks up a lumber ship to Cuba.

His eventual plan: “penetrating the tropical jungles of South America along the Andes to a tributary of the Amazon, and then floating down on a raft [like Aguirre Wrath of God in Werner Herzog’s film] to the Atlantic.” But there’s no ship heading that way, so he goes to California instead. Landing at San Francisco, he enquires the quickest way out of town to "anywhere – just so long as it's wild". The passers-by direct him to Yosemite.

The rest is Natural History…

Yosemite and Merced River By King of Hearts (Wikimedia Commons)

After walking the John Muir Trail (and, in the same season, the John Muir Way here in Scotland) I felt obliged to read up on the man himself. My book ‘Muir & More: John Muir, his life and walks’ has been on special offer from Vertebrate Publishing – buy Muir and More (£7 including postage) and get a free copy of ‘Walking the Literary Landscape’. (Cover and book illustrations: Colin Brash)

Grandfather Mountain to Asheville NC in June 2008.

Muir’s Journal was transcribed in 1916, after his death, and is unedited: otherwise he would presumably have gotten rid of the repeated ‘beauty’.

Away across the Atlantic, this was the wedding day of King George I of Greece, later assassinated. Three days later, the US would finalise the purchase of Alaska from Russia for $7.2 million.

It was a very useful article

Have just ordered your book. I wasn’t on their mailing list, so got an additional 20% discount. Not bad for two new books that both promise to be great reading. 🙂