Jane Austen Walks

What are men to rocks and mountains? The importance of the Outdoors in the 1810s. [1500 words 7 mins

"To the Lakes? What delight! what felicity! You give me fresh life and vigour. Adieu to disappointment and spleen. What are men to rocks and mountains? Oh! what hours of transport we shall spend!"

'Pride and Prejudice' (Jane Austen)

I’m getting in right at the beginning on Jane Austen’s 250th anniversary year. This essay is adapated from my 2022 version on UKhillwalking.com

So was there something in the air? The very start of the 19th Century also saw the start of two huge cultural movements. In August 1802, Samuel Taylor Coleridge set off on the nine-day walk around the English Lakes that inaugurated the sport of hillwalking: tramping the tops for exactly the reasons so many millions of us are at it right now. And just a few months later, Jane Austen makes her first sale, £10 for the manuscript of what would become Northanger Abbey: putting a rocket under the all-new art of the novel.1

Right from the start these two fundamental forms of fun were tangled up together. Those first fellwalkers all doubled up as poets, and within a few years a long-distance hike into the Alps would give us ‘Frankenstein’ and ‘Dracula’. Meanwhile it is a truth universally acknowledged, that no young person, of eighteen or twenty summers, may attain the rôle of heroine in Miss Austen's novels, without a keen appreciation of country walks. The other young ladies may spend their time in needlework, or passing on spiteful gossip, or playing on the pianoforté. But Elinor and Marianne, or Catherine Morland, or Lizzie Bennet: the way to spot the one that matters, is by her habit of hiking.

Sense & Sensibility

Jane's first novel, Sense and Sensibility, features heroine sisters Elinor and Marianne Dashwood. Living on the eastern edge of Dartmoor, “the high downs invited them from almost every window of the cottage to seek the exquisite enjoyment of air on their summits” – the location here would be the Raddon Hills, rising to 235m. Chapter Nine sees a literal (as well as literary) turning point in the narrative: a turned ancle (Regency spelling) for 'Sensibility', Marianne Dashwood, caused by fellrunning in unsuitable shoes.

And at the very end of the book, Marianne recovers her health, yes, but also her moral integrity: her determination to no longer flap around in the maelstrom of her own emotional displays like some social media influencer of the 21st century. How is this recovery marked? By a resolve to rise at six, and “take long walks together every day”.

Northanger Abbey

Catherine Morland, the star of Northanger Abbey, also likes to pull on her boots. “A new source of felicity arose to her… she had never taken a country walk since her first arrival in Bath. ‘I shall like it,’ she cried, ‘beyond anything in the world.’ ”

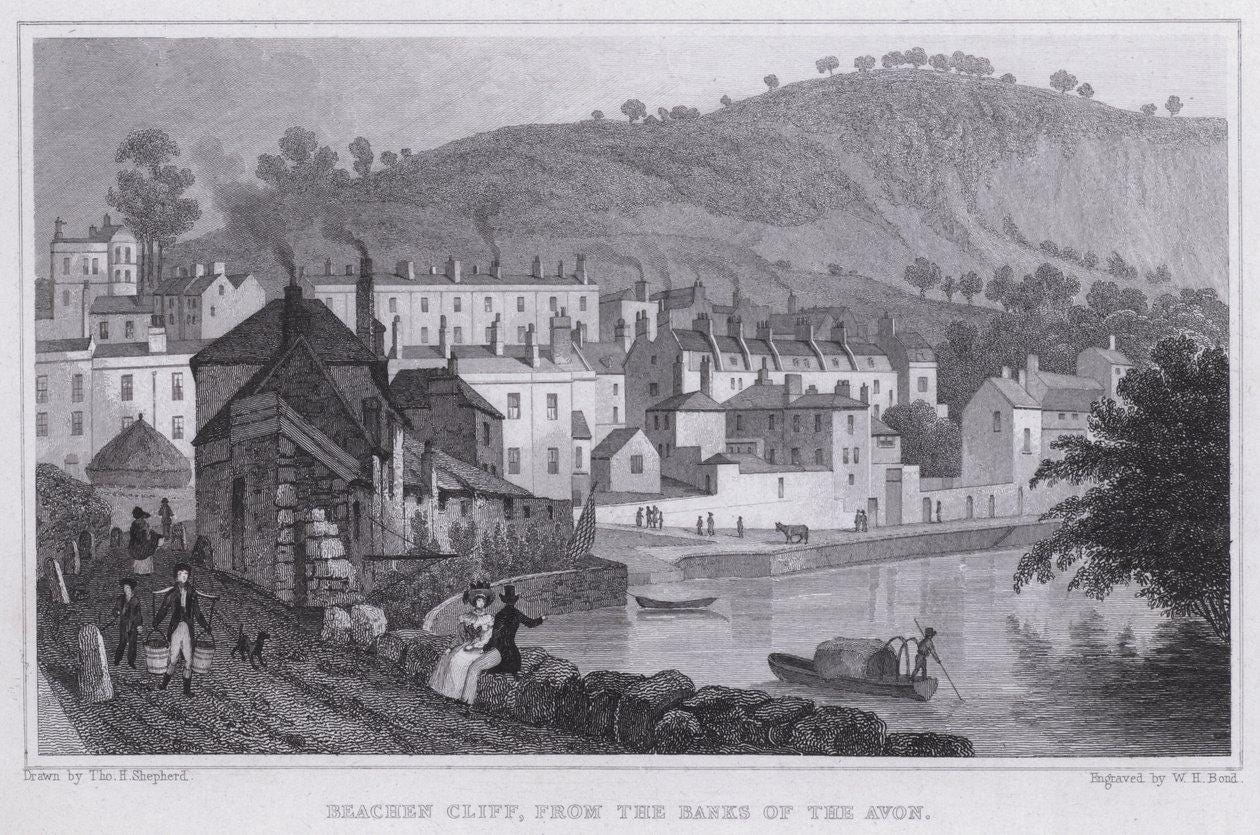

Northanger is, for me, the most fun of all the six, with its clever self-referential stuff and its witty put-downs. But it’s also notable for its ironic, affectionate, account of the early nineteenth-century art of landscape appreciation, with its “foregrounds, distances, and second distances—side-screens and perspectives—lights and shades; and Catherine was so hopeful a scholar that when they gained the top of Beechen Cliff, she voluntarily rejected the whole city of Bath as unworthy to make part of a landscape.”

Emma

Emma is the exception. It's her well-off, older brother-in-law, Mr Knightley, who has the fancy for country walks. And Emma does not approve.2

Having a great deal of health, activity, and independence, [Mr Knightly] was too apt, in Emma’s opinion, to get about as he could [ie on foot], and not use his carriage so often as became the owner of Donwell Abbey.

But surely, once he’s in the drawing room, does it make any difference whether he used his feet or his horse to get there? Indeed it does, says wrong-headed Emma. “There is always a look of consciousness or bustle when people come in a way which they know to be beneath them. You think you carry it off very well, I dare say, but with you it is a sort of bravado, an air of affected unconcern; I always observe it whenever I meet you under those circumstances.”

Emma’s never one to let mere logic and rationality stand in the way of her winning the argument… Emma, indeed, has a lot to learn. Not least, among her life lessons: the importance of country walks.

Persuasion

In all these stories, and even more so in Pride and Prejudice, there’s the same clear signal of who’s the goodie. It’s the one with the muddy hem and the hiking boots.

By the early 19th century, when Austen was writing and publishing her six immortal stories, the formal art of landscape appreciation had already been around for twenty years; invented by a chap called William Gilpin, with his Picturesque Tours of the Wye Valley and the Lake Country.

As vigorous hiking types, we're reading Austen for her commentary on outdoor sports. And for us, the chief fascination will be seeing Gilpin's ideas absorbing into popular culture, as looking at hills and rivers goes mainstream, and a long walk in the countryside begins to be a thing. Mr Tilney in Northanger Abbey has all the jargon at his fingertips. Marianne, in Sense and Sensibility, is a big fan.

Nobody in Jane Austen's novels seems to be aware of the Wordsworths, any more than Anne Elliot, at Lyme Regis in Persuasion, spots Mary Anning unearthing the plesiosaur on the beach below. But when Fanny Price, heroine of Mansfield Park, disapproves of ‘improvers’ who cut down trees; when Elinor Dashwood admires a hanging wood on a hillside – we see William and Dorothy’s ideas arriving in respectable drawing rooms.

To the extent that by the final novel, Persuasion in 1815, country walks are no longer just reserved for the heroine. In the few years since Pride and Prejudice (set around 1800), even the baddies have got their boots on. Anne Elliot, of course, well understands the mental health benefits: prescribing herself ‘many a stroll, and many a sigh’ to get over her agitation that Capt Wentworth’s brother in law is to become tenant of Kellynch Hall. (Chapter IV). A huge group hike occupies all of Chapter X: “[Louisa and Henrietta] were going to take a long walk, and, therefore, concluded Mary could not like to go with them” — and now it’s even the uncongenial younger sister Mary Elliot who “immediately replied, with some jealousy at not being supposed a good walker, ‘Oh yes, I should like to join you very much, I am very fond of a long walk.’ ”3

Pride and Prejudice

But the quote at the top is from Austen's best-loved novel: notable for Colin Firth's wet shirt sequence in the BBC series of 1995 (the shirt itself now on display at the Jane Austen Centre in Bath). Notable, too, for its tour of the Peak District. Eliza Bennet (Jennifer Ehle) climbs the Roaches (505m) for a spot of low-graded scrambling on Ramshaw Rocks.

And what is the moment when she realises Mr Darcy may actually have something going for him? It's the trees and rivers of his Derbyshire estate, and the ten mile long hiking trails laid out according to the most tasteful picturesque principles.

English Romanticism? Jane Austen doesn't have much time for the emotional excesses and the self-indulgent cultivation of the feelings. But when it comes to the grand new game of walking around in the countryside, and even up the occasional small hill: she comes down strongly in favour. And these two great innovations – the sport of walking and the art of the novel – set off hand in hand into the brave new nineteenth century.

Yes, I’m aware that a poet called Petrarch climbed Mont Ventoux back in 1336; and that Henry Fielding wrote Tom Jones way back in 1749. But Mont Ventoux is nothing but a bike-ride, and who today reads Tom Jones without a university salary as an inducement?

Book 2 chapter VIII

Louisa and Henrietta have a hidden agenda: they’re hoping to bump into a certain young gentleman, and don’t actually want Mary along on their walk.

Delicious. But Tom Jones - oy! Work of genius (Know it's tongue-in-cheek.) I do like William Gulpin, though - he made it so easy for the aspiring aesthete: three cows are better than two cows, two cows, one sheep even better (or words to that effect.

Didn't know about Petrarch shinning up Mount Ventoux (which always makes me think of lavender honey ("from the slopes of"). Such fun.

‘I shall like it,’ she cried, ‘beyond anything in the world.’ ". That's very good advice for all of us.. we all should like those walks more than anything in the world, at least while we're about them. And no country in the world outside England is more experienced, has a longer tradition or more support for hill walking.