Islands in the Stream

Bog problems: continuing the encounter with Rannoch Moor [1500 words, 6 mins

At daybreak, the sunlight flashes back from every peat pool – showing me just how much intriguing soggy bogland’s still to cross before my breakfast coffee at the railway station.

Last week’s post about the first day of this crossing is here .

I'm on the move at six: early enough for frozen fingers to have trouble fastening the boot laces. Early is important. Somewhere ahead lies the river Garbh Ghaoir (or Rough Gour) which drains Loch Laidon and by implication the whole of Rannoch Moor.

And before that, there was still the main part of Rannoch to cross: five miles of the shaggiest moorland, dotted with lochans and without any helpful hills rising above the moss. And even before that, there was the sunrise to see. The sky paling to greyish pink behind the jagged skyline of the Black Mount. The sky-shining lochans of the moorland floor coming alive like a dimmer switch slowly being turned up. And then the light spilling like runny golden custard across the moor, slurping around every hump and hollow, with the triangle shadow of the hill I've been asleep on stretching right back to where I'd left the West Highland Way 18 hours before.

Turning my back on all that, I head off my hill end towards the largest of the mid-moor lochans. Which is immediately lost to sight as I drop to moorland level. After the first mile on the compass bearing, my mind starts to re-enact some events of the Younger Dryas age ten thousand years ago. There's the peat swamp, an extra millimetre of rotted sphagnum moss for every year that passes. And there are islands of original scenery, paler coloured grass showing where the glacier-ground ground rises out of the peat. Those knobs and knolls growing slowly smaller as the black sea makes its yearly millimetre.

Away overhead the skylarks are in full song. Somewhere on the left, a grouse cackles. Somewhere on the right, the morning train to Fort William clanks its way northwards across the moor. Deer footprints are everywhere in the bare peat – and where a deer's tiny hooves only sink six inches, my feet can safely follow.

After an hour or two, I reach another lochan.

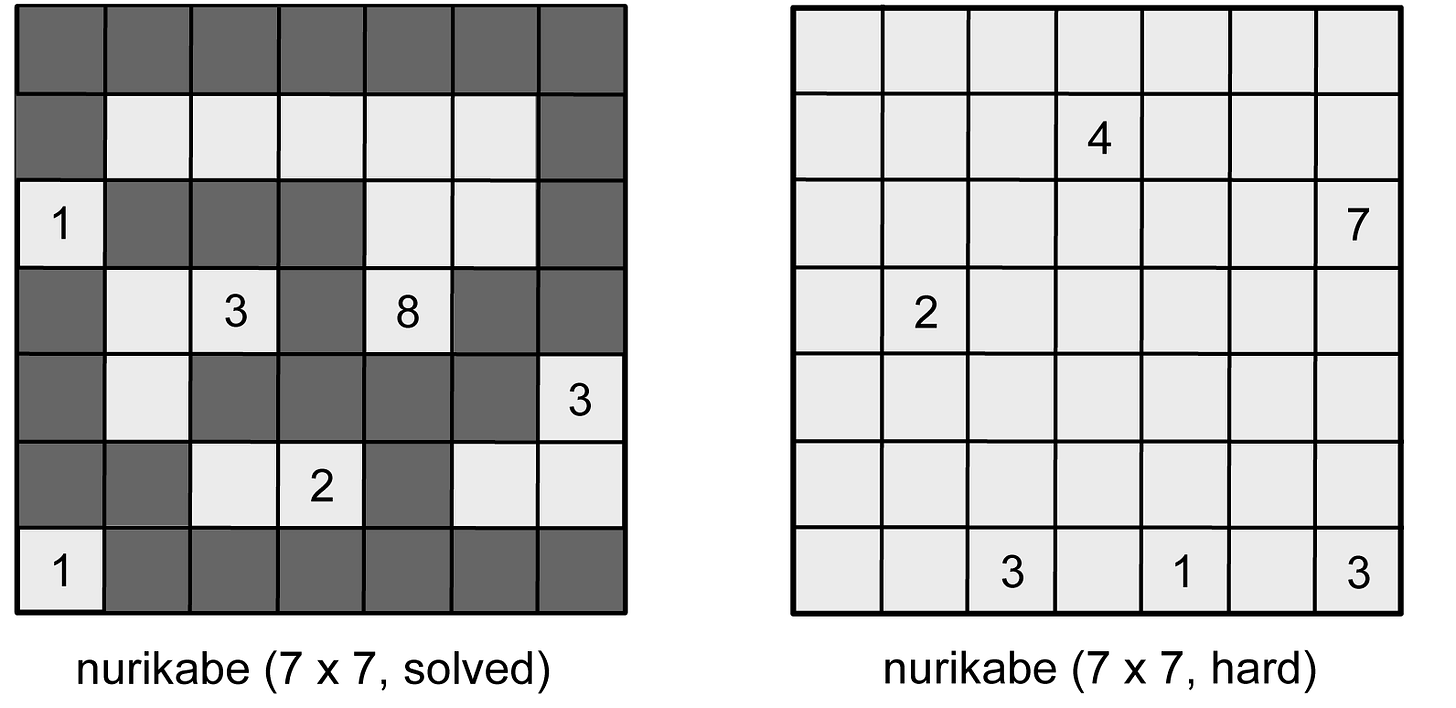

Rannoch Moor’s many lochans don't have edges, they just ramble out into the surroundings as black creeks and ponds of soggy moss. Crossing Rannoch is exactly like a Japanese logic puzzle called Nurikabe, except with wet feet, and no reset button.

Nurikabe (or 'Islands in the Stream') has somewhat confusing rules:

The cells of the box are colored with white and black islands, or Nurikabe streams. The islands should be clearly separated but allowed to make contact with the corners. Each island should contain a square of the number, and that number should represent the square of the island. The flow must be single Nurikabe continuous. All dark triangles are attached to the sides (not just the corners). In addition, the flow cannot contain a 2 square x 2 square pool.

The rules explained by a native speaker of English (me) in the footnote 1

The Nurikabe puzzle was invented in 1998. But the Nurikabe himself has been rambling about on Rannoch for a lot longer than that. Nurikabe's life purpose is to frustrate foot travellers, taking the form of an unclimbable, invisible wall which extends for ever in either direction. According to yokai.com, the online database of Japanese ghosts and monsters, this invisible wall materialises “right before your eyes”. He looks like a cross between a puppy and a large sack of cement. At least, he would do if he weren’t invisible. The ‘wall’ itself is formed of his supernaturally enlarged scrotum. Accordingly, a poke in the right place with a sharp stick may be enough to dispel the Nurikabe.

Hopefully then, I keep on poking my poles into the black peat of Rannoch. So which lochan is this, exactly? The C shape, along with absence of inlets or outlets, lets me name it as Lochan a' Mhaidseir. Now knowing where I am, I head north, to glimpse the Lochan Caol Fada (the Long Narrow Lochan), then bear northeast along slightly higher and drier ground. And the white Moor of Rannoch Hotel appears ahead – with the feared Garbh Ghaoir river running through the dip between.

But the bit of it right here looks crossable. And when I get there, the Rough Gour (at grid reference NN419567) is only knee deep. Confronting an expected danger or difficulty and discovering you can cope with it: this is one of the satisfying things in hillwalking. Slightly less satisfying is confronting an expected difficulty and finding it isn't actually difficult at all… Drying my feet on the heather, I don't know whether to be pleased or disappointed.

Rough moorland leads north to a final reedy pool. Is every Rannoch lochan equipped with two geese? Or is it the same pair, can't work out why the journey from Bald Malcolm's place – a three minute flight – has taken the silly human since 4 o' clock yesterday?

The last kilometre out to the café is where I find myself on a couple of steps of sinister quaking bog, bottomless peat slop skimmed over with matted grass. But the railway embankment is alongside, with a £50 fine for Trespassing on the Railway perhaps preferable to death in black slime.

No longer anxious about the Rough Gour river, I'd been worrying whether the station café would be open for late breakfast. But yes, they start baking at 7.30 for their lunchtime rush. I wish I could remember all the components of their lumberjack cake. Suffice it to say that it contains no chunks of leather boot, garish checked shirt or chainsawed-off fingers.

Why write a series of Substack posts about Rannoch Moor? Not because its granite and its heather and its hundred sparkling lochs are among the most-loved spots of Scotland. There is just one Instagram hotspot, the worn-out patch of roadside where you look across Loch na h'Achlaise into the Blackmount, with the lorries rushing at your back. But apart from that, Rannoch is more ignored than looked at. Not just because of the MacDonald cattle thieves and the drovers and the railway engineers and James Bond and Harry Potter, and the way that Rannoch’s empty acres hold the traces of those humans like scars from ancient battles.

The reason I write about Rannoch is a way of hearing what its empty acres have already told me – even when I cross in my tin box with the heater on and the sound system tuned to my algorithm’s favourite songs. How much more when I cross on foot, as the mountains step back into their world of clouds and spaces, leaving me alone beside the rain-grey loch.

Crossing Rannoch on foot is to learn again – despite our breathable nylon and GPS gadgets – a little bit of wholesome and appropriate fear. A reminder, a retrieval, of times when we needed to protect ourselves from wild nature – even if, now, it's wild nature that we need to protect from ourselves.

Alone on the moor, we feel the tragedy and the fragility of our short lives on the planet, with our tangled economic pathways and our gadgets. We become the MacDonalds who took the Campbell’s gold to drive the encroaching Macgregors out of Rannoch with flaming torches – and at the same time we are those Macgregors with the smell of burning thatch in our hair, looking at our children and wondering how many of us might live through the coming winter.

We follow the poets who come up out of the Lowlands, or out of England, James Hogg and Coleridge and Wordsworth. When they looked at Rannoch Moor, what did they see? And perhaps most clearly of all, the eye of the stranger: the visiting American, coming from smoke and cities, stepping out of his friend's car onto the bare earth verge of the A82 in the year that road was built.

Between the soft moor

And the soft sky, scarcely room

To leap or soar…

Memory is strong beyond the bone.2

The beauty of Rannoch is water, and bare rock, and grass stems bending under the frost. Time present, and time past, and the lonely cry of the curlew.

1. Each numbered square must be contained in its own light-square island of that number of squares. No other light squares are allowed.

2. separate light-square islands may touch at corners, but not along grid lines

3. The dark-square ‘stream’ must be continuous (squares adjacent along their sides)

4. No 2 x 2 dark-square ‘pool’ is allowed.

So in the example, you can add three dark squares around the [1]; and each bottom-edge dark-square must have another immediately above. This now defines the island around the right-hand [3].

Reminding me of enjoyable days on Dartmoor!

Enjoyable read. I think the footnote numbering has gone away.