Crossing bogs

Encounters with quagmires, morasses, bogs, fens, flows, sloughs and other soggy bits. [1600 words 7 mins

Here the crow starves, here the patient stag

Breeds for the rifle

TS Eliot 'Rannoch, by Glencoe' c 1935

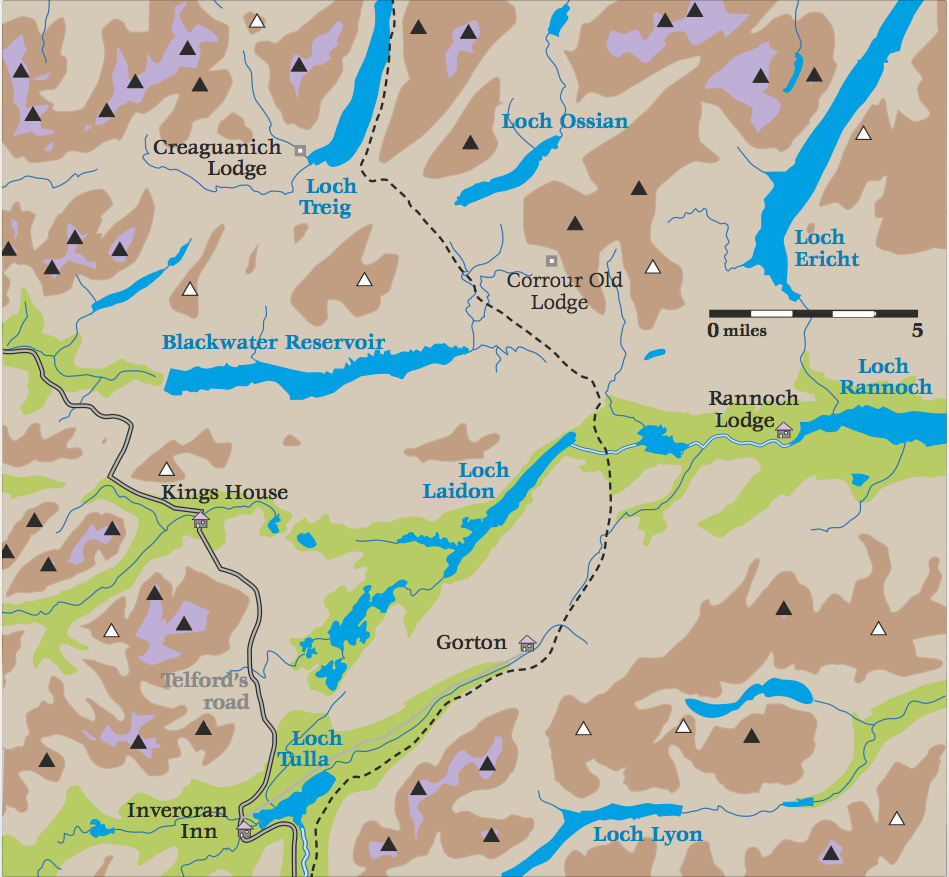

Look west from the summit cairn of Buachaille Etive Mor. You see the mountains, and you see the sea. But now look east. Peer into the wind, your waterproof hood flapping against your face. What you see is nothing much at all. Far below, at the foot of the mountain, everything goes flat for 12 or 15 miles. Brown heather and grey-brown rock, scattered all over with silvery-grey water. Streaks of river, and pools, and lochans, and slightly larger lochans, and a line of lakes right across the landscape.

All across the moor, the brown deer chew down the landscape to match their own short-cropped brownness. Heather lies in slow brown curves, roughened here and there where the granite bones poke through. Water in slow, black rivers, which smell of whisky and make little puffs and sighing like a sleeping baby.

"A real bog," says J McBain (The Merrick and the Neighbouring Hills 1928) "is a circumscribed expanse of the earth's surface that has been unable to make up its mind whether to become land or water." And he goes on to describe one:

… an expanse of mud, though not an unbroken expanse, but rather a network of ditches with watery surface and sub-stratum of mud of unknown depth, running in all directions, and communicating at all angles, with narrow banks between, on which a man might find precarious footing. These channels are comparable to nothing but stagnant open sewers filled with slush that smells with the smell of the dead and decaying debris of vegetable and insect life; and so far as uncleanness is concerned, one might as well get immersed in a cesspool as stumble into one of these slimy puddles.

Crossing such places will cause mental confusion, as well as very mucky knees.

They had been twelve days crossing the Neck, rumbling down a crooked causeway through an endless black gob, and she had hated every moment of it. The air had been damp and clammy, the causeway so narrow they could not even make proper camp at night, they had to stop right on the Kingsroad. Dense thickets of half-drowned trees pressed close around them, branches dripping with curtains of pale fungus. Huge flowers bloomed in the mud and floated on pools of stagnant water, but if you were stupid enough to leave the causeway to pluck them, there were quicksands waiting to suck you down, and snakes watching from the trees, and lizard-lions floating half submerged in the water, like black logs with eyes and teeth.

You might not have visited the Silver Flow, in the Galloway Hills (first quote). And you almost certainly haven't braved the dreadful, but fictitious, swamps of the Neck in central Westeros, from 'Game of Thrones' (second quote). But anyone driving up the western side of Scotland, anyone walking the West Highland Way, has to cross Rannoch Moor.

Which we do, easily enough, on the West Highland Railway that teeters across the peat on its bed of brushwood.

The Hogwarts Express crosses Rannoch Moor at the start and end of every school term. Not altogether straightforward, as the swamps and moraine humps are just ideal for ambushing the train.

It’s in Prisoner of Azkaban that the train’s raided by Dementors, who somehow hop aboard as the engine slows to the line’s summit at Corrour. Early on in the Half-blood Prince, as the train crosses the moor in beautiful autumn sunlight, Harry Potter is inconveniently turned into a floor tile by the malicious Malfoy.

In the Deathly Hallows Part One the train’s raided again, this time by Death Eaters. (Which aren’t the same as Dementors, by the way). Harry however isn’t on board, he’s skiving off school for a bit of backpacking through the Yorkshire Dales (finding Malham Cove magically cleared of its usual crowds) and the Forest of Dean. Usefully equipped with one of those really expensive lightweight tents that combine a tiny size packed down with a small marquee once opened out.

I could say a lot more about the train (and did, a bit, in an earlier post). Then, for motors and cyclists, there’s the A82 road that they build in 1934. Or, if we’re walkers, we use the firm gravel of the earlier road, the one built by Thomas Telford which edges along the base of the Blackmount1, like a Victorian lady keeping her skirts up out of the muck.

But if you walk down the Telford Road, midway between the ancient inn of Inveroran and the slightly less ancient on at the Kings House – just half way through the day-stage of those long-ago cattle drovers – and then simply turn off sideways?

What are the hidden gems of Scotland that most tourists never see?

… Then there is the amazing Rannoch Moor. Lots of tourists see this on their way to Fort William but never stop to actually look at it. Ranch Moor is a wonderfully atmospheric place that host many ghosts and spirits wondering around! Its not really a place you should think about walking across cos its full of peat bogs and you might end up being one of those ghosts.

Kate Isles, Artist born and bred in Scotland Answer on Quora 18/7/2017

Peat Hags

The Hag is astride,

This night for to ride;

The Devill and shee together:

Through thick, and through thin,

Now out, and then in,

Though ne'r so foule be the weather.

Robert Herrick ‘The Hag’ 1648.

The Night-Hag was drawn by William Blake as a fit-looking androgyne, with long braided hair and bronze-coloured wings, drifting above a black landscape half hidden by moonlit wispy clouds. Hag as in peat-hag is charmingly (and wrongly) defined in the Free Dictionary as meaning “a firm spot in a bog, or else, a soft spot in a moor”. This is a different word from the hag who's a nasty old woman. The peaty sort of hag derives from Old Norse högg, meaning a gap; the 'hewing' of wood is a related word.

Peat hags shouldn't happen as much as they do. The mat of plant life gets weakened by overgrazing of sheep and deer, or by airborne pollution – pollution which is paradoxical, as airborne nitrates would count as plant nutrients in more ordinary ground. The sedge and bog asphodel gets broken by the hooves of sheep and deer. The peat beneath opens out in dry weather, then scours away under sudden storms. Peat flakes are carried downstream, to silt up the rivers and reservoirs.

Global warming means more of both dry-out spells and sudden washouts. A report commissioned by Scottish Natural Heritage discovered that "climate appeared to be the principal driver of erosion", and concluded gloomily that "it is unrealistic to try to recreate peat-forming vegetation, due to the very long timescale involved”.

Having boldly abandoned the old Telford road, I dodge around a large lochan named for the son of red-headed Patrick2, and cross the first low ridge, into the first, mottled acres of peat and moorgrass.

Due east, across fourteen miles of heather and peat hag, granite boulders and slow black rivers and a hundred silver lochs, lies Rannoch Station on the West Highland Railway. Under my feet, the sphagnum moss is storing away carbon at its relentless one millimetre a year. Somewhere ahead, slow brown rivers carry that peat away, speck by speck, to clog the reservoirs of Glasgow. Red deer move silent on the peaty ground, drifting across like specks in my vision.

The grass is thin here, a stalk at a time out of black peat. On either side of me are pools and black gullies. As I get further into the moor I'm wondering whether, somewhere ahead, the waters will spread and join so as to stop my further progress.

The first lochan3 has washed into the surrounding peat, exposing tea-stained stumps and tree roots – the bones of the Old Wood of Caledon, re-emerging from the swamp that suffocated it thousands of years ago. Out on the grey water, two geese are gossiping urgently about something or other: perhaps the intrusion of me is interesting enough to need a good natter.

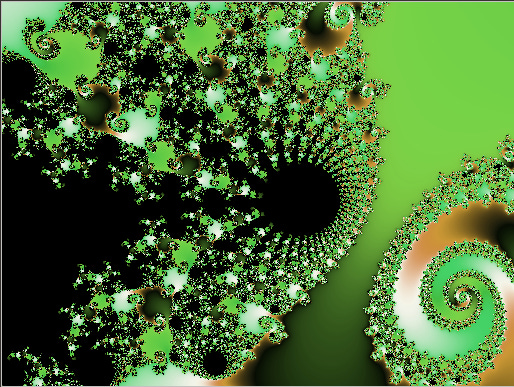

The ground beside the water is always going to be ambiguous. The second lochan has rambled out into the surroundings as creeks and ponds of soggy mos. Black peat and black peaty water: each penetrates the other like the mathematical entity called the Mandelbrot Set, the closer you look at it you still see it intermingling on a smaller and smaller scale.

As the shadows spread across the humps and small lochans, I shake the peat off my gaiters on the 547m hillock – it rises from the middle of the moor like the boss on a targe – Leathad Mor, or the Big Wide Item.

I spend half an hour looking for the prime peatbank: the one which is out of the wind, dry even at its base, and with a clear sightline back across the moor for the overnight scenery but also for the phone signal from the mast above the Kings House.

The sky is striped with cloud, but the low sun rakes across the lochans, to light up the hills of the moor's edge in rusty brown. Then it hits the Blackmount in a golden splash like an egg-yolk onto a hot saucepan. Luckily, the peat ground is lumpy enough to make sure I stay awake for every one of these late-evening lighting effects.

“Can tha blin lead tha blin? Wull the’ no baith faa intae tha sheuch?” Matthew 15 v14 in the Scots Bible.

If the blind lead the blind, they both of them fall into the swampy ditch. Next week, interrupting this short sequence from my ‘Swamps and Bogs’ sub-theme with a piece about me and John Milton

Or Black Mount, I’m not bothered

Lochan Mhic Pheadair Ruaidh

Lochan, a small loch. Loch, the Scots, and Scots Gaelic, word for a lake

I've always enjoyed looking over at Rannoch Moor from the mountains to the west, and once from a Corbett to the east and the mountains around Loch Ossian. I've not yet ventured onto it. Too many worrying legends...

In Gaelic, leathad generally translates as a modestly inclined slope, making Leathad Mor "Big slope". Also, I believe Pheadair is the genitive of Peadar, thus meaning of (red) Peter, rather than of (red) Patrick.

Your writing is a treat. I feel like I need to kick mud off my boots.