From the Alps to Bloomsbury

George Mallory, Everest climber, lives on in a novel by EM Forster. [1700 words, 8 mins

Did Mallory go all the way? Mountaineers mostly agree, however intrigued by the possibility, that he never actually made it. The trouble with that one is, the bloke he made it with was a minor Bloomsbury-ite called James Strachey, brother of the more famous Lytton; and James wrote a detailed blow-by-blow account of the intimate moment. Several in fact, to all his closest friends.

Oh, you weren’t actually asking about his brief sortie into gay sex? You’re more interested in Everest… In that case you want last week’s posting.

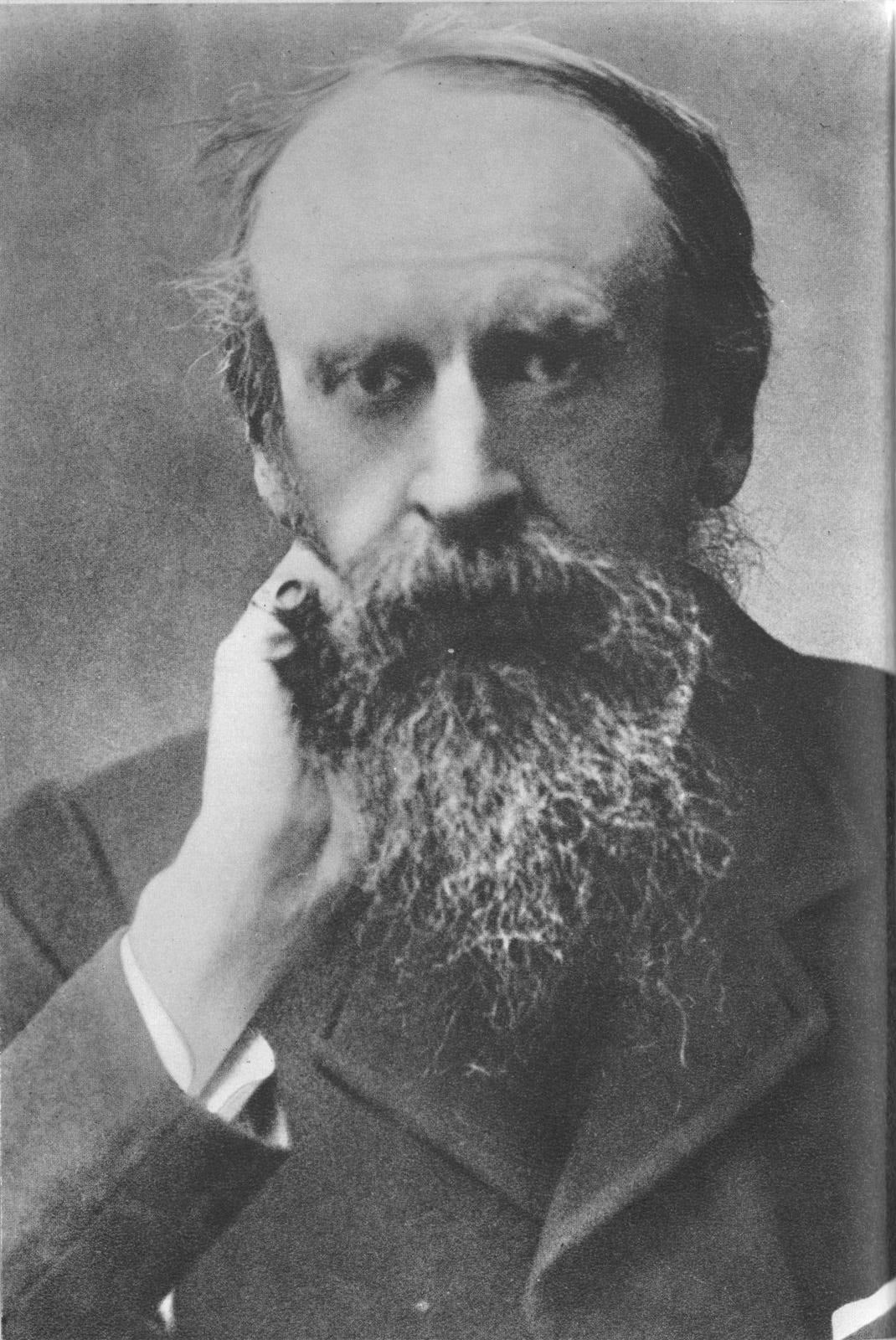

George Mallory, photographed by Duncan Grant

Before the First World War, in England, there were three separate groups of interesting people. There were the Cambridge intellectuals known as the Apostles –flirting with socialism and also with each other, mainly based at Kings College. They included art critic Roger Fry, economist Maynard Keynes, poet Rupert Brooke and novelist EM Forster.

A hundred miles or so to the west there was the group of mountain climbers led by Geoffrey Winthrop Young, creating difficult new routes on the crags of Snowdon while reading classic literature in the evening. And in the leafy squares around the British Museum there was, of course, the Bloomsbury Group. Cambridge University overlapped with the climbers, and also with the Bloomsbury Group. But just one man, George Mallory, found himself at the intersection of all three.

Leslie Stephen, Alpine Club President

The Alps and Bloomsbury are a long way apart: the denizens of Bloomsbury elegant and urban, the Alps athletic and outdoors. Their common ancestor is Sir Leslie Stephen, the father of Virginia Woolf and Vanessa Bell – but also the leading mountain climber of his time, author of the classic The Playground of Europe.1 As a writer, philosopher and intellectual, he still considered his chapter describing a sunset ascent of Mont Blanc as the best thing he’d ever written. While as a climber, with his guide Melchior Anderegg he made first ascents of the Zinal Rothorn and the Schreckhorn.

Ascent of the Rothorn, frontispiece from ‘The Playground of Europe’. And yes, this really is what the north ridge looks like: a wonderful climb, especially with more modern protection methods.

And it seems that, through her father, Virginia Woolf must have met a climber called Lily Bristow, she of the Matterhorn and the second ascent of the Aiguille du Grépon. Because the painter Lily Briscoe in To the Lighthouse seems to be named after her.

Meanwhile, at Virginia Woolf and Vanessa Bell’s house in London, the Bloomsbury Group was beginning to meet. And in doing so, maintained a slender connection with the mountains. Sir Leslie had been president of the Alpine Club, and the painters in the group, Vanessa Bell with Duncan Grant and John Nash, used the club’s gallery for their early exhibitions.

At the same time, they (the men in particular) were getting their woolen long-johns in a twist over this handsome, adventurous and wild young mountaineer called Mallory. “He has the head of a Greek god,” wrote Virginia Woolf. As for James Strachey: “Mon dieu! George Mallory! He’s six foot high, with the body of an athlete by Praxiteles, and a face – oh incredible – the mystery of Botticelli, the refinement of a Chinese print, the youth and piquancy of an unimaginable English boy…. The sheer beauty of it all is what transports me.”

Handsome George was painted by Duncan Grant – the nude portrait with red-speckled background is now at the National Portrait Gallery. But more Botticellian is the one by Simon Bussy, a French painter, friend of Matisse, who married Lytton and James Strachey’s sister Dorothy and became a sort of expatriate Bloomsbury-ite. George Mallory visited Simon and Dorothy in their French home, possibly as a way of escaping the attentions of James Strachey, and went for some walks in the Alpes Maritimes above the Mediterranean.

George Leigh Mallory by Simon Bussy, pastel 1910, National Portrait Gallery, London

Room with a View

But the most telling portrait of George isn’t by a painter at all. It’s by EM Forster, as ‘George’ in his novel of 1908 A Room with a View.

“There is no need to call him a wicked young man,” says buttoned-up cousin Charlotte Bartlett – she’s the Maggie Smith rôle in the Merchant ivory film of 1985. George has just kissed Lucy Honeychurch at a violet-strewn viewpoint above the River Arno. “But obviously he is thoroughly unrefined. Let us put it down to his deplorable antecedents and education, if you wish.”

“It is quite possible he may be a Socialist,” adds the Revd. Mr. Beebe.

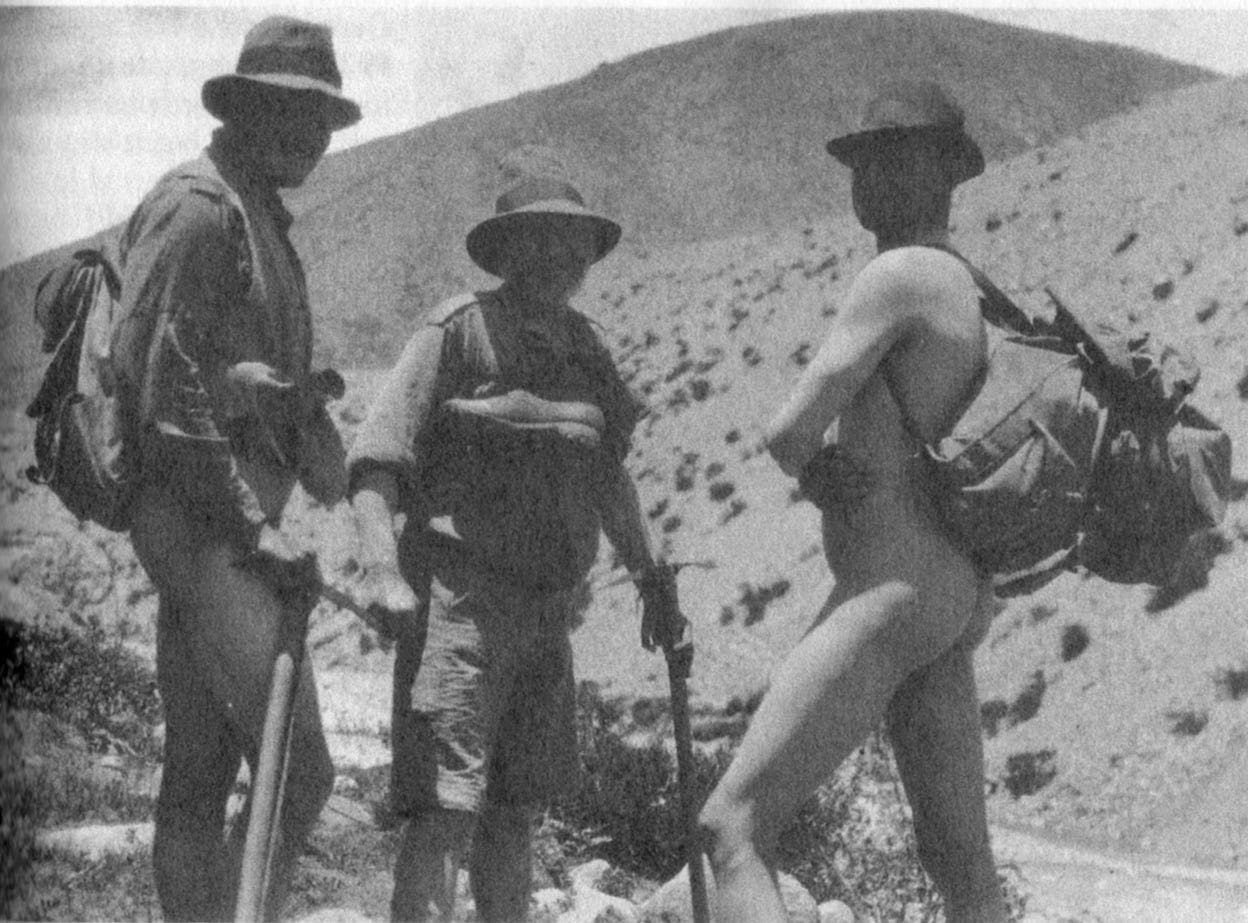

And so glamorous, Bohemian George Emerson stands alongside the Sacred Pool, “bare-foot, bare-chested, radiant and personable against the shadowy woods” – and most clearly identified with George Mallory by their shared habit of naked bathing.

George Mallory (right) preparing to cross a river on the way to Everest in 1921

Simon Callow, Rupert Graves and Julian Sands strip down for swimming in ‘A Room with a View’ (Merchant Ivory (1985)

Re-reading A Room with a View, I found it funnier than I remembered: in particular the tiresome minor characters Cousin Charlotte and lady novelist Miss Eleanor Lavish. And it transcribes beautifully into the Merchant Ivory film, with its cast including Judi Dench (as Miss Lavish), Daniel Day-Lewis, Denholm Elliott and Simon Callow. But it’s most notable as the first break-through not just for the two directors but for Julian Sands as George, and Helena Bonham Carter as Lucy.

“I loved it. My first imtimation of the possibilities of fiction” – Zadie Smith. Cover: Chris Silas Neal.

Just like George Emerson, Mallory fell in love with his future wife the ‘Botticellian’ Ruth Turner in a flower-filled Alpine meadow. Though in that case, life was imitating art, five years after Forster’s novel.

The match between George Mallory and EM Forster’s George was picked up by Mallory’s biographers, Peter and Leni Gillman2. Hunting for any academic following-up on this, my search for ‘Room with a View’ combined with ‘George Mallory’ found a different link: the actor Julian Sands, who played George in the film, quoting George Mallory’s “because it’s there” explanation of Everest.

Because Julian Sands, too, became a mountaineer. Gabriel Byrne wrote, in his Guardian obituary:

As a climber, Julian was fearless, though he knew the dangers well enough. He sought the freedom which comes from acceptance that nothing matters beyond the moment, step by slow step to the summit. Most mountaineers understand that the true summit is within. The high point on a peak is simply that, but the experience of the approach, the face or the ridge, up and down, is where true fulfilment is found.

For again, life has been imitating art. Julian Sands died in January last year, while hiking in the Baldy Mountain area of California – like George Mallory, his body lost for months under the falling snow.

“One comes to bless the absolute bareness, feeling that here is a pure beauty of form, a kind of ultimate harmony,”– George Mallory wrote to his wife Ruth in 1921. But for the public, there remains only his throwaway epigram on why one climbs Everest, his portraits by Bussy and Duncan Grant, and his transcription into Room with a View.3 Along with the enduring mystery of whether he, with companion Sandy Irvine, may indeed have been, 100 years ago this summer, the first to ever climb Everest.

George Mallory (below) and Edward Norton at 8100m on Everest, 1922

Photo: T Howard Somervell

My article about Leslie Stephen and his book is on UKclimbing.com . And if footnotes are for distant and unexpected literary links, here’s part of Thomas Hardy’s poem of 1897 comparing the Shreckhorn with Leslie Stephen:

Aloof, as if a thing of mood and whim;

Now that its spare and desolate figure gleams

Upon my nearing vision, less it seems

A looming Alp-height than a guise of him

Who scaled its horn with ventured life and limb,

Drawn on by vague imaginings, maybe,

Of semblance to his personality

In its quaint glooms, keen lights, and rugged trim.

The Wildest Dream, 2000. A winner of mountaineering’s Boardman-Tasker Award, and “by far the best and most intelligent account of its over-exposed, under-considered subject,” according to mountain writer Jim Perrin.

Could also mention here his work as an eccentrically liberal and inspiring teacher at Charterhouise school: “The most important thing that happened in my last two years [at school] was that I got to know George Mallory… From the first, he treated me as an equal…. George Mallory did something better than lend me books: he took me climbing on Snowdon,” wrote the future poet and novelist Robert Graves. It is purest co-incidence that George’s young swimming companion in ‘Room with a View’ was played by Rupert Graves; the assumption that the two are related is incorrect.

Excellent stuff Ronald! I'm very much enjoying your witty and well informed pieces about mountains and the people who climb them. Onward and upward! Jx

I thoroughly enjoyed this wonderful post, Ronald. And such beautiful accompanying images. Thank you :)