Did Mallory make it?

Did George Mallory and Sandy Irvine reach Everest's summit on 8 June 1924? Here's all of what we know. [2400 words: 10 mins

You’re high on a major unclimbed mountain: a famous one, that everybody’s heard about. It’s after mid-day, and you’ve been going for six hours already, over tricky, dangerous ground of rock steps and loose snow. Ahead of you, a clear ridgeline leads on towards the top: you reckon it’ll take another three or four hours.

If you go on upwards, you’re going to run out of oxygen and then get benighted. You don’t have any bivouac gear, and nobody has ever survived a night out at this height, not ever. Or if not a bivvy, then descending in the dark over what you’ve just come up would be almost impossibly difficult and dangerous.

On the other hand, you might just make it back down again still alive. Who knows?

So – do you turn back? Or are you going to go for it?

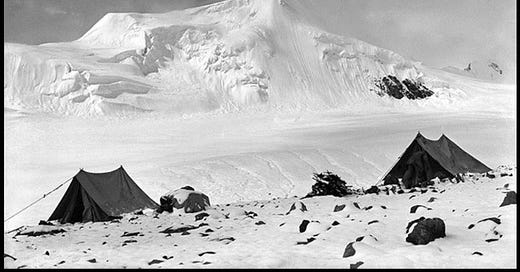

Mallory and Irving leaving the North Col, 6th June 1924 (photo Noel Odell). In one of the tents behind, Edward Norton lies snow-blinded.

On 8th June 1924, George Mallory and Sandy Irvine set out for Everest’s summit from a high camp on the mountain’s north ridge. Just after midday Noel Odell, a teammate lower down the mountain, saw the two of them about half way there, at a point called the Second Step. They were never seen again – until Mallory’s body was discovered, further down the mountain, in 1999.

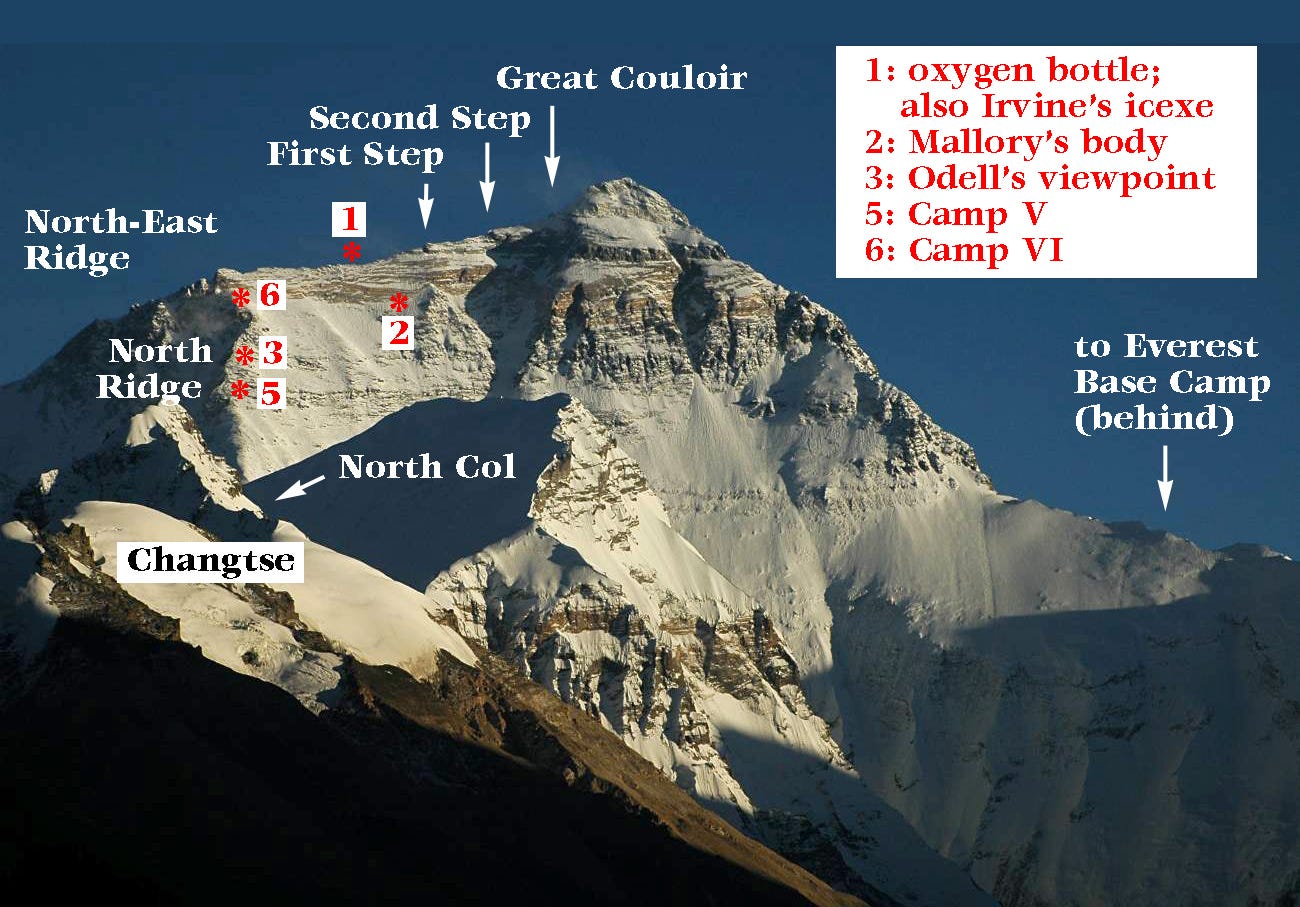

Everest from the north (Wikimedia Commons, marked up by me). Changtse obscures the lower part and the North Col. The approach is by the East Rongbuk Glacier, out of shot down to the left. The ridge on the right is the Tibet (China) / Nepal border; most of today’s ascents are from the south, round on the other side of the mountain.

Here’s what they set out to do, some time before daybreak on that final morning of their lives. Their start-point, Camp VI, is at 8170m, 200m (vertical) below where the North Ridge runs up to join the North-west Ridge at 8380m. Then it’s almost 1km along this ridge, which is moderately angled but interrupted by the two rock steps. The First Step (8500m) is a mere scramble, but the Second Step (8580m) is small cliff, with rock and ice running up to a 10m rock wall.1

Above the Second Step, the ridge runs into the summit pyramid, a snowslope with a further 250m of height to gain to the summit at 8848m.

Not long after midday, teammate Noel Odell saw them high on the ridgeline above him. In his diary, he wrote simply: “At 12.50 saw M & I on ridge nearing base of final pyramid.” In his press dispatch a few days later, he gave more detail:

There was a sudden clearing of the atmosphere above me and the entire summit ridge and final peak of Everest were unveiled. My eyes became fixed on one tiny black spot silhouetted on a small snow-crest beneath a rock-step in the ridge; the black spot moved. Another black spot became apparent and moved up the snow to join the other on the crest. The first then approached the great rock step and shortly emerged at the top; the second did likewise. Then the whole fascinating vision vanished, enveloped in a cloud once more. There was but one explanation. It was Mallory and his companion moving, as I could see even at that great distance, with considerable alacrity …

The next piece of evidence is Sandy Irvine’s iceaxe, found by climbers in 1933 about 250 yds downhill from First Step. It was lying on a slab of rock, as if dropped or put down in a hurry – normally you stick your axe upright into the snow. In 1991 two abandoned oxygen bottles were found, at about the same point on the mountain.

Then in 1999, Mallory’s body was found on the slopes below the north-west ridge, roughly below Irvine’s iceaxe. He was still tied on the climbing rope, and there were abrasions at his waist showing that he’d taken a fall and been held. His leg was broken and he had a dreadful wound in his head.

Mallory’s goggles, looted from his body in 1999 and displayed at the Rheged Centre, near Penrith. His body remains on the mountain.

The telling detail is the smoked-glass goggles, which were in his pocket. If your goggles are misted up and you want to see better, you push them up on your forehead, ready to snap them back in place to protect your eyes. (Two days before, at the North Col, Mallory had passed teammate Edward Norton snow-blinded from pushing up his goggles for too long.) If your goggles are in your pocket, that means you don’t need them any more. Which suggests that, when he fell, he had been climbing in the night.

Meanwhile not in his pocket was the camera that, according to the Kodak company, could still a century later have viable film inside it. Also not there was the photo of his beautiful wife Ruth. He carried Ruth’s photo with him always; but according to his daughter Clare, he’d promised to leave it behind him on the summit.

Timings

Mallory’s Camp VI was slightly lower than the point where today’s climbers set out for their 12-14 hour summit day, with much lighter and more effective oxygen equipment, and a ladder in place on the Second Step.

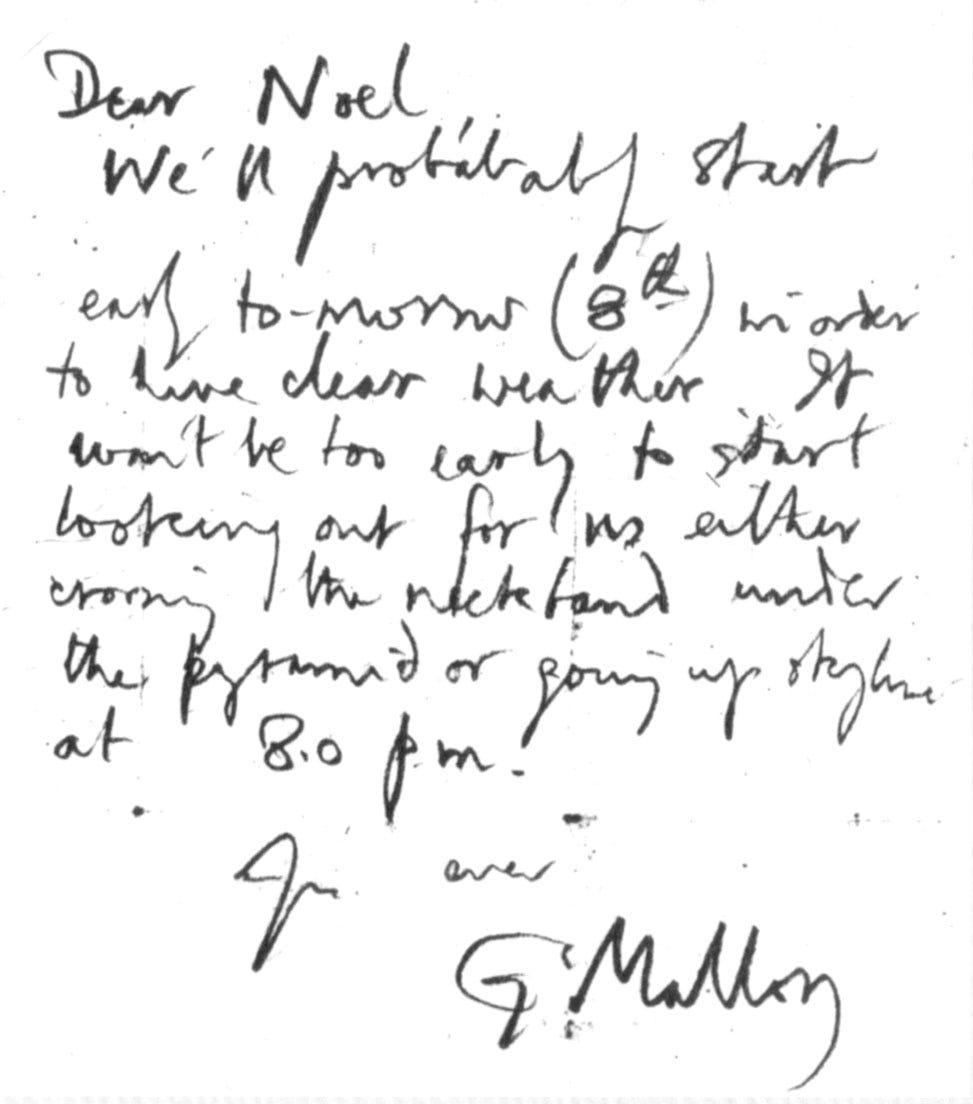

Those climbers start around midnight, and Mallory too had planned an early start. “We shall be starting by moonlight if the morning is calm,” he wrote to his wife Ruth; and to the backup team: “Dear Noel, We’ll probably start early tomorrow in order to have clear weather. It won’t be too early to start looking out for us either crossing the rock band under the pyramid or going up skyline at 8.0 pm.” [he means 8 a.m.]

Their oxygen sets carried two bottles each. At the set flow rate of 2.2 litres per minute, these would have lasted seven hours. Their oxygen bottle found not far below the First Step: if this marks the changeover to their second cylinder, that would indicate 3 1/2 hrs climbing at 80m/hr vertical ascent from their overnight at Camp VI. A good climbing speed, though slightly too slow to reach the summit in seven hours before their gas ran out.

But already there’s an inconsistency with Odell’s sighting. A pre-dawn start and 3 1/2 hours of climbing would get them to the First Step around 8am, as indicated in Mallory’s note. Not at just after midday, as spotted by Odell.

There is a possible explanation. When their tent was recovered, bits of oxygen equipment were scattered about the floor. The oxygen kit was dodgy: Sandy Irvine was the expert at fixing it – one reason why he was the one up there with Mallory in the first place. Maybe they spent four hours fiddling with the oxygen kit and set off really, really late.

I don’t actually think so myself. Mallory was pretty sure the hill could be climbed without oxygen; he’d have said, screw that let’s just go.

Odell’s boulders?

But that’s not the only inconsistency. The few minutes to get up the Second Step, as observed by Odell, is not plausible. The Second Step, as we now know it, is a short but serious climb: the first man recorded to have climbed it took over two hours. Whatever Odell saw, wherever he saw it, it wasn’t at the Second Step.

And maybe he didn’t see them at all? At such a distance (he was more than 300m below them, and perhaps 1km away) it’s all too easy to mistake a boulder in the snow for a person, and almost as easy to persuade yourself that you’ve seen it move.

And now I read that in 1933, Frank Smythe and Eric Shipton saw two companions in exactly the same place, ahead of them near the Second Step. Two companions who were, indeed, only boulders.

So my suspicion is, as the oxygen cylinders suggest, they passed the First Step, roughly as planned, around 8 or 9 am.

Ruth and George Mallory – George in uniform as artillery officer during World War One

Could Mallory have climbed the Second Step?

The Chinese expedition of 1975 fixed a ladder up the Second Step, used by almost every climber since then. However, Spaniard Oscar Cadaich climbed it 1985 without using the ladder and without bottled oxygen, and so did the Swiss Theo Fritsche. Both rated it 5.7 – 5.8 US grading; Mallory would have called it 'Very Severe but not Hard Very Severe'. Conrad Anker, who’s climbed it twice, has assessed it a bit higher at 5.8 – 5.10.

Anker was in crampons. Mallory, one of the most talented climbers of the 1920s, was wearing the heavy nailed boots of his time. According to my late father, this footwear is better than crampons on snow-covered rocks. Sidetracked magazine’s editor Alex Roddie, one of the few people still alive to have tried climbing in nailed boots, shares my Dad’s opinion on this.

Before any of them, in 1960 the Chinese made the disputed, but now generally accepted, first ascent of the North Ridge route. (Or, given Mallory and Irvine, perhaps the second…) Wang Fu-zhou climbed the Second Step in his socks, starting the difficulties by clambering up his partner. Wang took three hours, and lost all of his toes to frostbite.

Today’s ladder is 4.6m long, but you don’t go right to its top. Instead climbers must make an exposed traverse off to the right. Combined tactics, the posh name for standing on your partner, was a standard technique of the 1920s – and Sandy Irvine was nice and tall! Potentially leaving Mallory, one of the most accomplished climbers of the 1920s, with 2.5m of VS or HVS rock to climb, in the ideal form of footwear.

Me, I think he did it.

This post may be getting too long for a Substack’s email servers. If your reading this as an email, and get abruptly cut off, please hit ‘view in browser’ at the top of the page.

Where and when would they turn back?

Which brings us back to the question at the top of the page. You can get to the summit: but if you do you’ll be benighted and probably die. Most normal people will go no thanks, I’d like to stay alive. But climbers aren’t normal people. And for climbers, this one can go either way.

A few days before, expedition members Howard Somervell and Edward Norton, without oxygen, had reached the base of the Great Couloir around midday – they’d traversed along the North Face below the Second Step. Howard Somervell had had enough, but Norton was fit to go on. He decided instead to descend, while daylight lasted, and while still alive. In 1933 Frank Smythe, at much the same point, made the same decision.

But in 1975, on Chris Bonington’s expedition up Everest’s Southwest Face, Doug Scott and Dougal Haston got through the final steep rocks and ice late in the day, just in time to return down their fixed ropes to their top camp. Instead they went for it, upwards to the summit, without bivouac gear, at an altitude where nobody had ever survived a night out in the open.

I asked Doug about this after one of his lectures. What was he thinking? “Well,” he said, “we’d got through some nasty bivvies above Glen Coe…”

Two days later, “Mick Burke... took a calculated risk, which I suspect many of us would have taken, when he went for the summit of Everest alone in 1975. He almost certainly reached the summit but was overtaken by a storm and probably fell through the cornice on the way back." [Chris Bonington’s expedition account, my italics]

And George Mallory? He’d promised his wife Ruth not to get killed if he could possibly help it. But there’s later testimony from Noel Odell, who was climbing beside him right up until his death.

I know that Mallory had stated he would take risks in any attempt on the final peak. The knowledge of his own proved powers of endurance, and those of his companion, may have urged him to make a bold bid for the summit.

And his climbing companion Geoffrey Winthrop Young formed the same view:

Difficult as it would have been for any climber to turn back with the only difficulty past – to Mallory it would have been an impossibility.2

So that’s the decision point. Turn back now, while we still can – or go on, and get benighted. And whatever Odell and Winthrop Young may think, it could go either way. But once that point is passed? After you’ve already accepted that you’re not going to get down again in daylight? Few, if any, will turn back in the time interval after benightment is already inevitable but before reaching the summit.

Maybe the two of them started late, at 8am say, because of problems with the oxygen, and did indeed get to the Second Step around 1pm. Maybe Mallory tried to climb the Second Step, and kept trying until their oxygen ran out around 4pm. Maybe they turned back then, but moving at snail’s pace because of dehydration and not having the oxygen any more; got benighted, just a short way back down the ridge; and fell very shortly after that.

But the alternative seems to me more likely. That Mallory climbs the Second Step. Maybe Irvine also, with help from the rope, or maybe Mallory goes on alone. The oxygen would give out, but their oxygen equipment was bad enough that this wouldn’t be the sudden gasping for breath it is for today’s climbers. He reaches, or they reach, the summit, just as the sun goes down. He buries Rose’s photo in the snow. And exhausted, with no more oxygen, they turn to face the long, difficult descent as the light gradually goes.

And if, as Mallory slipped on a snowcovered foothold in the darkness, Irvine after dropping his axe had been just alert enough to belay the rope over a convenient boulder, they might have returned safely to the North Col. Mallory, now without his toes, would have dropped a couple of climbing grades and rediscovered his long-suffering wife Ruth as a climbing partner. And together they would have opened up some amusing little rock routes in north Wales.

The first people to reach Everest’s summit were Ed Hillary and Sherpa Tenzing Norgay in May 1953. Except, just possibly, they weren’t. When they asked Ed Hillary about it, he said: well it only counts if you come down again still alive.

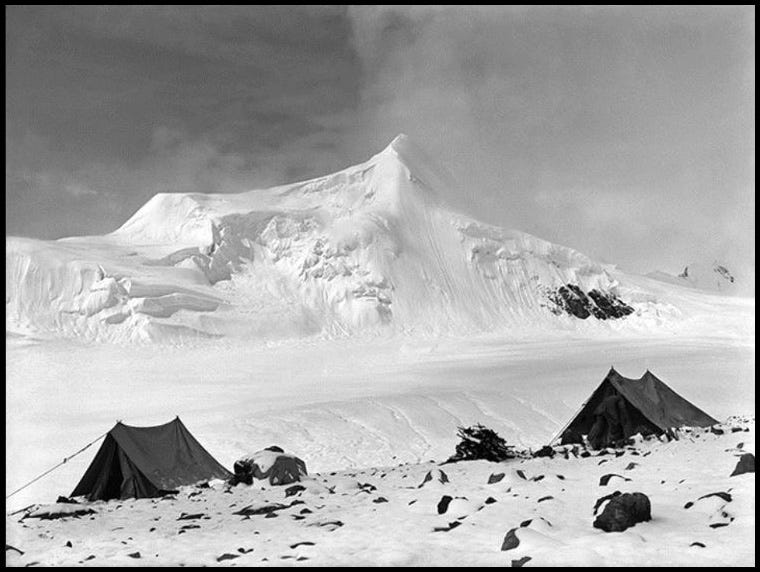

Camp at 20,000ft in cloudy weather after snowfall, photo George Mallory 1921

So who was George Mallory, and what were the life choices that brought him to death on Everest? Next week I plan to post about his place on the fringes of the Bloomsbury Group and inside a novel of EM Forster.

In fact everybody who climbed with Mallory saw him as a ‘bold’ climber, ie a risk-taker. The poet Robert Graves, who as a schoolboy climbed with Mallory in Snowdonia, wrote: “Anyone who has climbed with George is convinced that he got to the summit and rejoiced in his accustomed way without leaving himself sufficient reserve of strength for the descent.” Goodbye to All That, 1929.

Fascinating read. Love the connections you make to writers and literature, and the insights into what motivates these climbers in their lives on and off the mountains, and what we might do in their place.

Very stimulating account of this story, Ronald!

Mark