Emily Bronte and the Bog Burst of 1824

A near-death experience for two little girls may have helped inspire 'Wuthering Heights'. [1800 words 7 mins

The 2nd of September 1824, and the Parson, worried, went upstairs to look out of his window. Not his east window – the one above the graveyard whose acrid small drifted through both his church and his own home: the badly drained and insanitary graveyard that was slowly killing off his family one by one1 – no, as the clouds drooped heavy over the rooftops and the rain clattered on the slates, he was looking through the window on the opposite side. The window looking up over the moors.

Four hours before, his two daughters and their brother, along with two slightly unreliable teenage servants, had gone out for one of their favourite walks. They weren’t back yet. And the rain was getting harder.

As he stood peering through the raindrops that streamed down the glass, he heard the first rumble of thunder. Except – that wasn’t thunder. A ‘deep, distant explosion’ – and then a roaring noise, like a river in spate. Even as he listened it was getting louder. And the window frame under his hand: it was beginning to shake.

An earthquake, he assumed. He was wrong about that: Yorkshire doesn’t suffer from earthquakes in any serious way (okay, the occasional tremor along the Craven Fault, down Ingleton way). What he was hearing was a bog burst, high on the slope of Crow Hill. A wall of peaty water and mud, seven feet high, tumbling down Ponden Cleuch, small boulders swept along in its flow: the surge tearing away the stream banks, breaking through stone walls, carrying away bridges and leaving the fields buried in inches of chocolate-brown slime.

Next day, the Leeds Mercury reported on the singular disaster:

“The torrent was seen coming down the glen before it reached the hamlet, by a person who gave the alarm and thereby saved the lives of several children who would otherwise have been swept away.”

Their names weren’t recorded in the paper, but we know who they were. Emily Brontë, aged 6; Anne Brontë, aged 4; and their older brother Branwell, aged 7, along with the two teenage servants. Caught in the sudden rainstorm, and the hail that accompanied it, they’d taken refuge in the porch of the nearby manor farm, Ponden Hall. The bog surge had crossed the ground they’d just walked over, roaring down Ponden Cleuch just 100 yards from the old stone house where they stood shivering under the stone porch.

Ten days later, the event was written up by very minor Yorkshire poet John Nicholson:

Lines on the bog bursting in Yorkshire.

The summer's heat the heaps of peat

Had dry'd in many a gaping chink

And when so dry the clouds on high

Send down a flood to give it drink

And as each flaw with greedy jaw

Quaft with unsatiated thirst

The lightnings flasht, the thunders crasht

And its tremendous bowels burst …

The scaly fry in myriads die

And eels full half a century old

No more can creep amid the deep

But helpless on the flood are roll'd

Leeds folks amaz'd in terror gaz'd

The river's contents beat their skill

But news went down to that great town

A bog had burst upon a hill.

“I ever thought it very natural,” the poet explained: “for the drought of last summer would dry the moor ground till it opened in chinks, and the thunder storm passing over the bog the waters would get into the fissures, or perhaps a water spout might accidently fall upon that particular spot and be the cause of the phenomena.2”

The two young girls must, we can be sure, have been traumatised by this near-death experience. Then again, perhaps not… Emily, at least, seems to have been thrilled to bits by the natural disaster. Twelve years later, she would recall the exciting event in an early poem ‘High Waving Heather’.

All down the mountain sides, wild forest lending

One mighty voice to the life-giving wind

Rivers their banks in the jubilee rending

Fast through the valleys a reckless course wending

Wider and deeper their waters extending

Leaving a desolate desert behind

‘Jubilee’ – the original meaning is a day of rejoicing. Emily personifies the peat-flood as hugely enjoying its downhill surge, “bursting the fetters and breaking the bars”.

The very head of Ponden Beck has been over-deepened by the flood that surged down it in 1824, carved out into a hollow surrounded by little rocky crags.3 The place is known as Ponden Kirk, and features a small through-cave with legendary qualities: crawl through it with a suitably gendered companion and within the twelvemonth you will either be married to each other, or else both dead and haunting the place with your ghostly presences.

But in Wuthering Heights it becomes ‘Penistone Crags’: shining in the evening sun, longed for by the younger Cathy (Cathy Linton) growing up at Thrushcroft Grange in the valley below.

My sister Kate was on the phone. Ronald, what are you doing in this book I’m reading? The Chessmen by Peter May, and yes: acknowledgements to “Ronald Turnbull, walker, writer and photographer, for his crucial advice on mountain walking”. The book was published in 2013, by which time I’d quite forgotten the email enquiring about routes into those magnificent craggy valleys of north Harris.

The book’s bog-burst takes place during the night, during a storm, while the two protagonists are high on the moor, taking shelter in a stone beehive dwelling:

[Fin Macleod] woke to a sound like the end of the world, and felt the earth moving beneath him, as if the whole mountain was shaking …

“What the hell’s that?”

The noise roared, even above the blast of the storm, filling the air, the ground fibrillating all around them. “Feels like an earthquake,” Fin shouted above the noise.

… The next time he awoke it was daybreak, which is when he had found Whistler out on the ridge in that strange, pink dawn light, looking down into the vanished loch where Roddy’s plane lay canted among the rocks.

That bog-burst actually happened, among the peaty hummocks where the Isle of Lewis changes its name to become the Isle of Harris. One day in November 1959, the Loch nam Learga, 200m long and 1.2m deep, was found to not be there any more. The peat between the loch and the slope top 40m away had been breached and washed down the slope, along with the slope itself, leaving the bare bedrock of Lewisian gneiss.

Bog-burst events are not, in fact, all that uncommon. One list going through the historical record counts up 4 in Scotland, 9 in the Pennines incuding Emily Brontë’s one, 5 in Northern Ireland and 26 in the Irish Republic – Ireland having not just more peat but also more rainfall.

Most recently, one in 2020 at the southern fringe of the Mourne Mountains polluted the Rivers Derg and Mourne Beg, damaged a trout hatchery, and interfered with the construction of a windfarm. Dept of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs Minister Edwin Poots said: “The scale of the damage is shocking, the devastation caused by the peat slide to the local river systems is very serious and there is substantial ongoing damage inflicted.”

As readers expert in bog geography will already be aware, peatbogs come in two basic sorts. The peat slides described were in upland blanket bog. But they happen more spectacularly, and even more surprisingly, in lowland raised mires: bogs that build up actually above ground level, fed by rainwater and held together by capillary action within the sphagnum moss. Given a long sunny spell that dries out the surface, and then a few days of very heavy rain, the bog itself explodes suddenly sideways, covering nearby farmland with brown peat-slime.

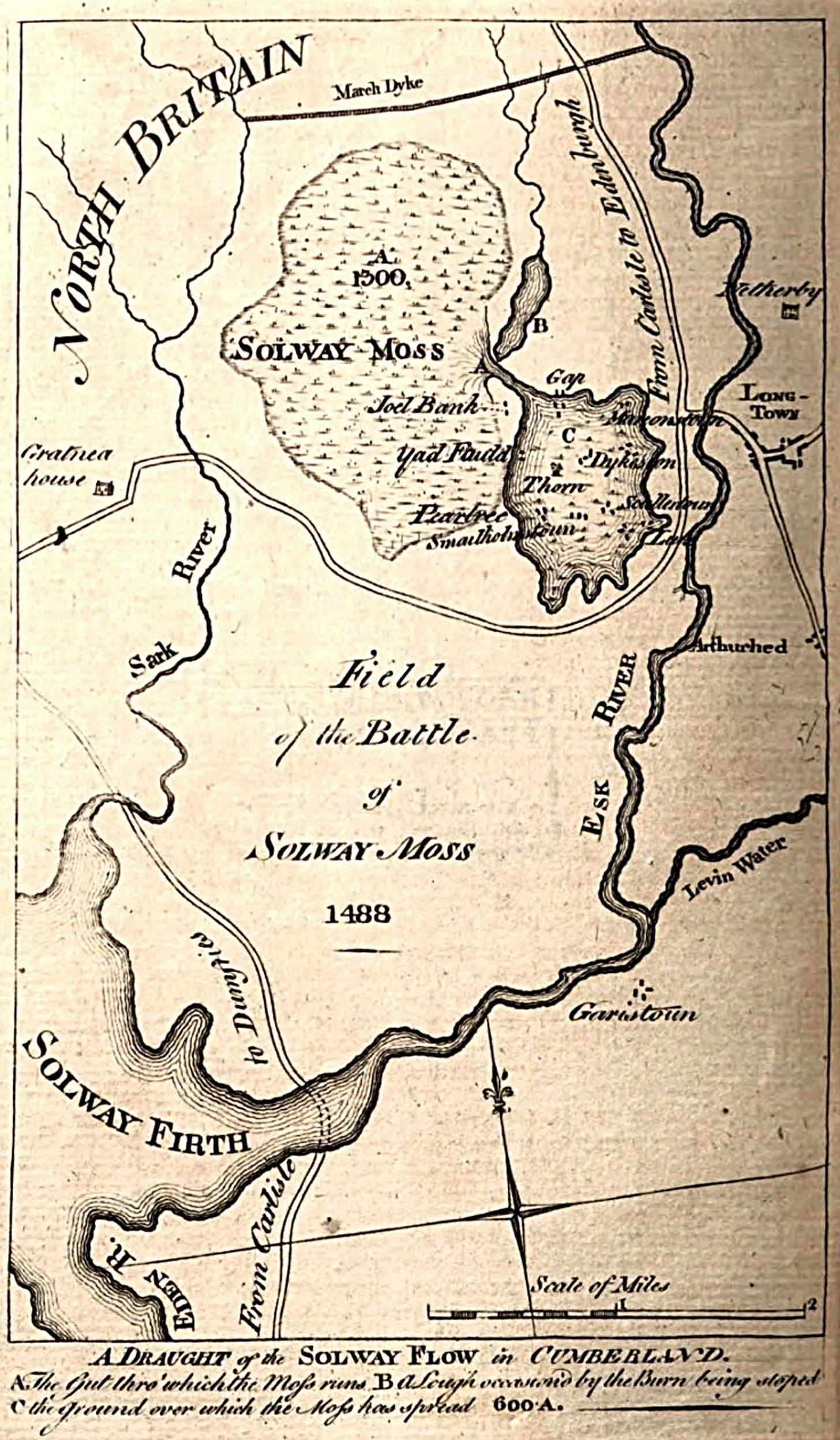

The Solway Moss, on the Scottish border near Gretna, is where several hundred Scots drowned in the marshland after their defeat by the English West March Warden Lord Wharton in 1542. Two hundred and twenty nine years later, on a November night, the bog itself erupted. It destroyed a dozen farmsteads and their livestock, and covered 400 acres (1 1/2 square kilometres) of good farmland in up to 5m of infertile peat. Never successfully farmed since, the ground is now under the Army’s Longtown ammunition depot.

In December of 1792, in Portnard, County Limerick, a peat-slide 1/4 mile wide travelled for a full mile, overwhelming three cottages and killing 21 people as they slept.

Even so, bog bursts remain a rather rare sort of disaster: Emily Brontë was very unlucky to run into one. Or, as Emily herself may have seen it, really lucky…

For the disaster site, which must have been ravaged and raw through all the time she was growing up, would supply a crucial location for Wuthering Heights itself; where Ponden Kirk was renamed as ‘Penistone Crags’.

The abrupt descent of Penistone Crags particularly attracted her [Cathy’s] notice; especially when the setting sun shone on it and the topmost heights, and the whole extent of landscape besides lay in shadow. I [Nellie Dean] explained that they were bare masses of stone, with hardly enough earth in their clefts to nourish a stunted tree.

Already, for the book’s older Cathy, the rock hole below the crag has become the Fairy Cave, where witches are gathering elf-bolts to hurt the cattle with. A generation later, the younger Cathy (Cathy Linton) is growing up at Thrushcroft Grange in the valley below. Fascinated by the sight of the crag, aged 16 she heads up there on her little Galloway pony. And of course, just over the hill is Wuthering Heights, and her dead mother’s sinister lover, Heathcliff himself.

When the graveyard was closed for sanitary reasons in 1883, it was said to contain the remains of 40,000 people. On Google Earth the graveyard occupies around 7000 square metres: which would indicate 11 cadavers to every 1m x 2m plot.

… showing that the use of ‘phenomena’ as a singular noun goes back at least two centuries.

How far was Ponden Kirk a pre-existing feature, and how much was it carved out by the bog-burst? I’m not a geomorphologist, and I’m speculating a bit here based on my own observations.

Well, I’ve never heard of bog bursts before. It might be something we become more familiar with if global weirding continues to produce droughts followed by storms…

I've just returned from a trip to Haworth, and re-read Wuthering Heights, so I really enjoyed this little insight into their life and times.