Dying on the Eiger – Part 2: the Mittellegi Ridge

The Eiger North Face: who would want to climb that lethal thing? Meanwhile me and David are doing the Mittellegi, the ridge that runs along the top edge of it. [2200 words, 10min

In 1936, and in last week’s post, two brave Bavarians and two adventurous Austrians attempted the lethal North Face of the Eiger: the last of them, Toni Kurz, dying of exposure, frostbite and exhaustion a few metres above the waiting rescuers.

Thirty-five years later, my friend David and I rode up the Eiger in the underground railway, and climbed the Mittellegi: the ridge that runs along the top of that north face.

And another thirty-five years after that, with three companions from the Mountain Bothies Association, I spent a winter’s day reslating a roof; and after an early supper sat in darkness watching the DVD of The Beckoning Silence, the dramatised documentary made by Louise Osmond, based on Joe Simpson’s book.

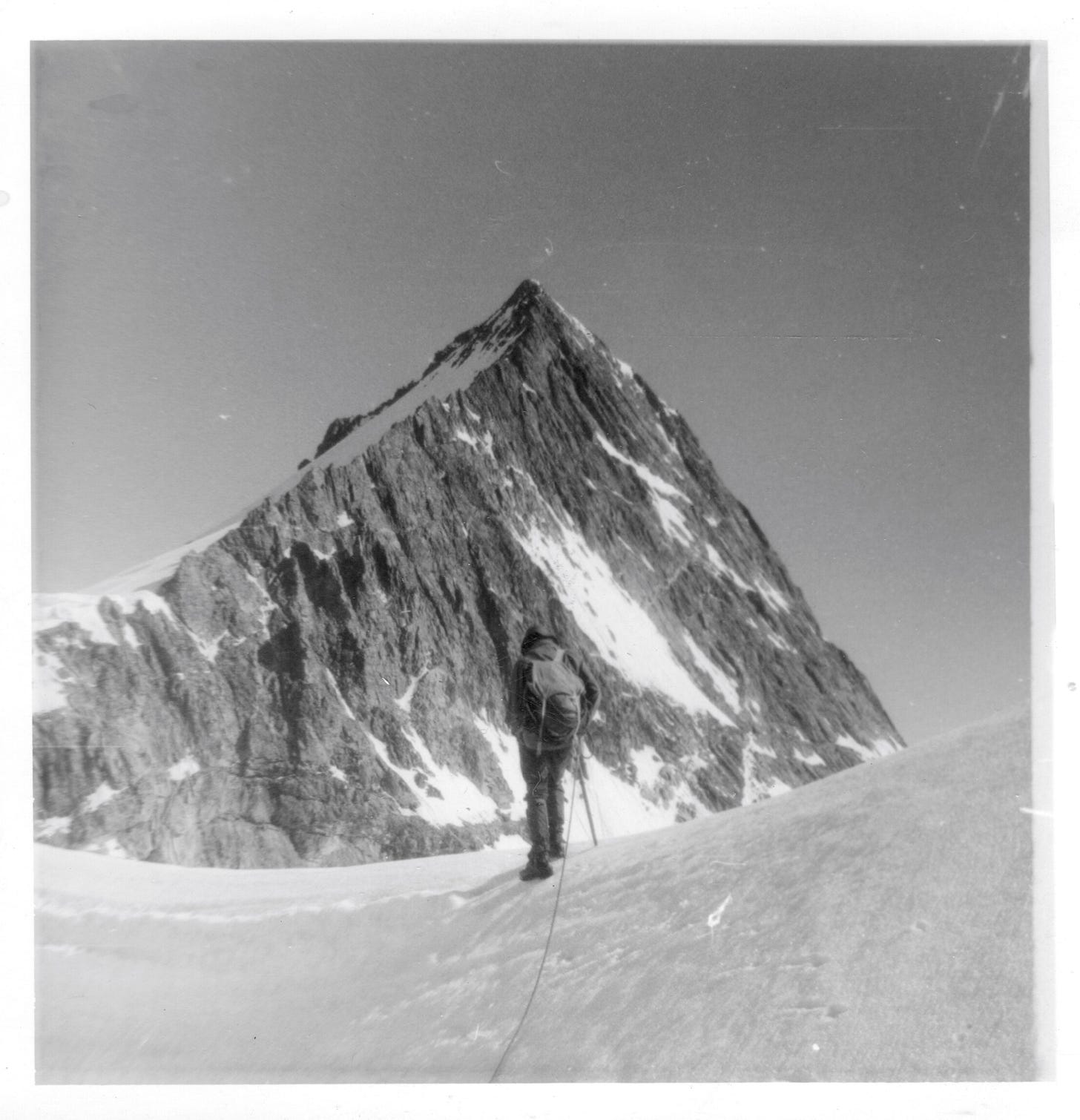

Looking up the Mittellegi Ridge to the Eiger summit, Eiger North Face on the right; helicopter shot from ‘The Beckoning Silence’

More than one person, knowing me as someone who’s climbed the Eiger, has wanted to know why Toni Kurz needed to die like that. Adding – for the photo from The White Spider, copied on into subsequent books, was used again in the movie – 'such a handsome young chap, too’.

I start by explaining that I have never been that sort of mountaineer. Our route up the Eiger passed inside the North Face on the underground railway, before finding a quite different, easier, and decidedly less dangerous way towards the summit. During the train ride, we leaped out at the Eigerwand station and sprinted down the tunnel to the window, the one so dramatically looking down that dreadful north face.

The next stop after Eigerwand is called Eismeer. Here we got out again, but this time with our rucksacks and ice axes. Under dim light bulbs we walked down a corridor whose walls, rather than being decorated with posters for the next West End show, were rough brown limestone streaked with damp. Light seeped from ahead, and we stepped down onto the glacier on the south side of the Eiger.

We headed along the foot of the rock wall until it angled back. Then we made our way upwards on what would be, in the UK, extremely bad scrambling. The rock slabs were gentle, but covered in rubble. Not difficult, but the ground was slightly dangerous, and we worked our way upwards avoiding any sudden movements.

And then we were on the high and sudden ridge. A few minutes above us, on the ridge crest, stood the Mittellegi Hut. Except, the hut is slightly wider than the ridge, and overhangs it on either side. This turns out convenient when it comes to the sanitation. In most huts at that time, the toilet facilities were a simple pierced plank in a separate shack suspended over some nearby precipice. In the Mittellegi Hut, the pierced plank was within the building.

Mittellegi Hut, evening [Photo David Howard]

Behind the hut the ridge rises in that swooping curve I was to see on my TV screen on the roof-repair weekend. But we didn't look at that. We went into the hut, sniffed the blankets in hope of finding a clean one, and started cooking our supper.

At five the next morning we peered out to see how serious the weather was. The Mittellegi Hut leads only to the Mittellegi Ridge; the alternative is to go back down the rubble-covered slabs and pay for the train all over again. Even one-way, the train ride had been expensive. Accordingly, there were good reasons for the clouds not to be terribly serious ones. We breakfasted on stale baguette – which, when eaten stale, gives a little squeak when you bite it. (After a fortnight in the Bernese Oberland we'd already derived all the fun there is in squeaky baguette.) We made a nice cup of hot tea that wasn't actually very hot due to the altitude of 3350m. We neatly folded our blankets and – a real treat, this – strapped on our crampons indoors, with our gloves off.

In grey dawn, we stepped out onto the ridge. And gradually, as the light strengthened, we became aware of what we were standing on. Writing my postcard home I joked that the right hand side of the ridge drops vertically – it is, roughly speaking, the North Face of the Eiger itself. Meanwhile the left hand side actually overhangs. The helicopter shot on the Joe Simpson DVD reminded me how close this absurdity comes to being true. The right-hand, northern, edge drops steeply for a few metres, and then all you see is the green valley and Grindelwald nearly 2000m below. And as on the North Face, as the people down there started their day the two-tone horn of the postbus, and the clank of the cow bells, drifted up the vertical grey wastes of the north face to us at the top.

One of the flat bits on the Mittellegi Ridge [photo: David Howard] [The old photos were never captioned: David thinks this is somewhere that isn’t the Eiger…]

The left-hand, southern, side, undercut by the lively Eismeer glacier, does indeed overhang here and there. Mostly, the ridge crest is narrow enough to look down both sides at the same time. On the left, a few feet of snow and rock and then the Eismeer Glacier, 1000m below. On the right, a few feet of rock and snow and then the cow pastures and rooftops of Grindelwald.

And in other places, the ridge rises in rock towers that must be climbed around – with one or other of the big drops cooling your bootheels from below. Or else climbed over, which means that where the drops are concerned, you're poised over both of them at once. We climbed the rock sections one at a time using belays – rock anchors on the rope – taking turns to lead. The rock is firm and storm-scoured and grippy. The level bits of ridge carried a cap of soft snow. There we walked together, the principle being that if I fell down one side of the ridge, David would immediately jump down the other. Then, when everyone had finished swinging around, we'd both just climb back up the rope.1

The climbing was not difficult. It was, thankfully, just difficult enough to keep our eyes away from the view, most of the time. Some slabs on the northern flank were even equipped with a fixed chain for handhold and, in my youthful arrogance, I was a bit disappointed about that.

"But Ronald - you do realise where we are?" What did he mean – we were on the Mittellegi Ridge, slightly down the right hand side. Yes, but slightly down the right hand side means what we're actually on is: The North Face of the Eiger. And we know what happens on The North Face of the Eiger. The weather closes in and it ices up. And then things get really nasty.

Mittellegi Ridge, upper part: Wetterhorn behind [rather blurry photo: D Howard]

But really nasty is what it wasn't. The Mittellegi, by virtue of its situation high up in the sky, is entirely free of falling stones. And it is about five grades of easiness easier than the Eiger’s North Face. For me at 20 years old, the mountains were about the beauty, and the situations. But on top of that, there was also the excitement of being in places potentially, apparently, of high risk, but being in control, within my capabilities.

But that is, also, exactly how it was for Toni Kurz. He was strong and confident, he had the skills and he had the gear. He had the right companions. The possibility of death didn't come into it. The difference between me as a mountaineer, and young Toni from Bavaria, was that his belief was not in accordance with the evidence. Meanwhile, 1000m higher up along the Mittellegi, my faith in my own non-mortality was, of course, entirely well founded.

What is surprising about the Eiger North Face is quite how strong and forceful the evidence is that you need to disbelieve in order to even start off up the thing: the evidence of mortality. The year before his own climb, Toni Kurz had watched the Italians Sedlmeyer and Mehringer head up to their first miserable bivouac. The following day he'd seen, or certainly heard about, their climb on up into the storm; and any telescope would show him the corpse at the Death Bivouac.

A year after Toni Kurz’s climb, two climbers called Vörg and Rebitsch would climb just 300 metres before they came across the first of the corpses. It was Hinterstoisser, as it happened. They gave up on their ascent and carried him down the mountain. On the successful 1938 ascent, Vörg and Heckmair hoped to avoid dead bodies so as not to be obliged to stop yet again and carry them down.2 The British climber Don Whillans came across a climbing boot in quite good condition. Inside the boot was someone's foot. Accordingly, he deposited the boot at the Eigergletscher Station's lost-property office. Bonington and Clough made the first British ascent in 1962. During the first hours of the climb, so as not to discourage one another, each refrained from drawing to the other's attention the bloodstains and bits of bone on the rocks.

Me and David, on the Mittellegi, it was all quite different. Our faith in our own survival was evidence based, and sensible. Well, we didn't pass any bodies, did we?

After the Mittellegi the classic continuation is over both ridges of the Mönch, to Jungfraujoch railway station. But when you've been straining legs, and nerves, for six or seven hours, it's easy to decide to stop doing that. Besides, the weather really wasn't good. In fact, it was starting to snow. We decided to go down the West Flank, which was the Eiger's normal and easiest line at that time before the collapse of the Eiger Glacier.

Looking back, with some relief, up the Eiger’s northwest flank in the rain, North Face just round on the left {photo David Howard]

A ridge of soggy snow leads down through cloud. Below, things widen out to a confusion of slabs, and loose stones, and short steep walls. The edge of it all was defined by the sudden darkness that was empty air and the North Face.

About a third of the way down, the blank wall of the Rote Fluh tops off on the Western Flank, in a shoulder where you can stand and look out over the face. The cloud slumped apart to show us the smooth limestone walls, and ledges covered in slush, and loose, near-vertical gullies lined with dirty ice and dropping into black emptiness. At this point, just 12 years before, frustrated rescuers had stood and listened to the Italian Stefano Longhi. At 44 years old, Longhi was on his first ever Alpine ascent, persuaded to it by a younger companion who had now abandoned him. The curve of the face brought his voice across to the rescuers like a whispering gallery from the ledge below the Traverse of the Gods where he was dying of cold and starvation.3

This glimpse across the face showed us how far up the mountain we still were. Anxious about the routefinding, we pressed on downwards. Somewhere on these snowy ledges, in 1961, had been found two other members of Longhi's party. This led to a rewriting of the record books. They had not died, as previously believed, in the Exit Cracks above the White Spider, but later, on their descent from the summit. Accordingly, they were retrospectively credited with the North Face's 14th ascent.

So why should such attractive, such alive young men wish to die on the Eiger? Simpson, in voice-over at the end of the film, gives his answer. “It’s not justifiable by any rational terms. [A pause. He nods to the camera.] That’s probably why you do it.”

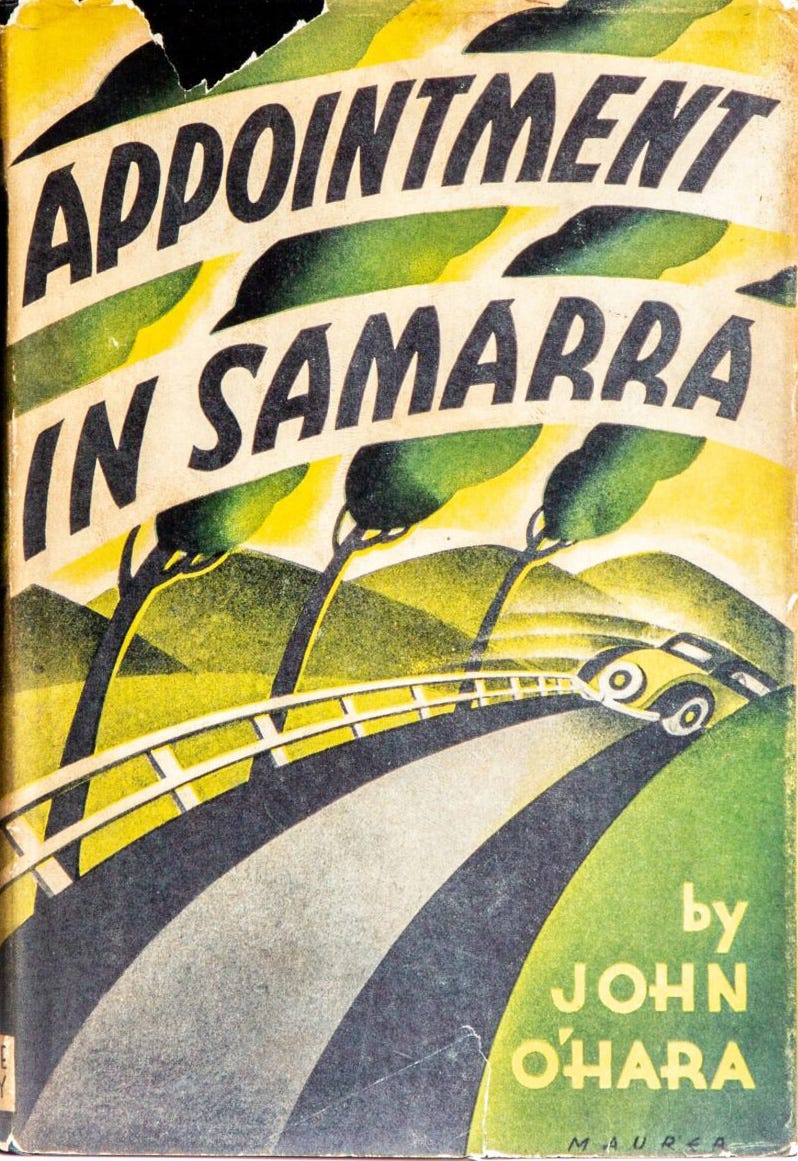

That's okay in a drama-documentary. In cold print, it rather too obviously doesn't make sense. Joe Simpson’s book, being a book, is more articulate. The Beckoning Silence – the full phrase is 'the beckoning silence of great height', but taken on its own, it just means Death.4 In its opening chapter, Simpson and his friend Tat embark on a roadside ice climb above the appropriately named village of La Grave in the French Alps. There's a thaw going on and the ice is soggy stuff, bad. Fifty metres up, Simpson, while belayed from the unsound piton which is their only protection point, suffers an attack of rationality. He decides that the risk of death is too great to be entirely enjoyable. So they abseil down off the unsound piton.

The next day they decide that a predawn start will render the ice less unstable, and return to the climb. The ice is just as bad as before, and once again Simpson is terrified. But having abandoned the climb once already, they now feel obliged to complete it.

Two chapters later, after a near-miss from an ice avalanche in the Bolivian Andes, Tat (Ian Tattersall) decides he doesn't like doing this stuff any more. Tat's decision is presented as a tragical and incomprehensible collapse. And, in mountaineering terms, that is what it is. (Tattersall would die in 1999 in a paragliding accident.)

So Joe Simpson does not answer this question. It's enough that in the contemplative final section of his book, he does, in a moment of philosophical daring, get to the point where he asks it. That the Eiger is a worthwhile place to die is, for mountaineers, a self-evident given.

In black and white, Tony Kurz dangles, dead, on his iced rope 1000m above the cow-pastures of Kline Shadegg. Peter folds his computer down to darkness. For a moment the moon lies on the scrubbed kitchen table, and coal glow leaks around the stove door. We shift in our chairs, and murmur, and switch on the lights.

Tomorrow, there’s a lot more of the roof to be re-slated. An early night, now, that would be a good idea.

Approaching the Eiger summit. The slope to right is the summit icefield of the North Face route. With thanks to David Howard for company on the Eiger, for taking the photos, and for searching them out and scanning them 50 years later.

A 9-minute video of an ascent of the Mittellegi by Andres Vourakis is here . A lot more fixed rope on it nowadays, and the hut is busier too.

On Everest, today, the ethics has altered. If you stopped for bodies, then nobody would ever climb the thing.

An account of this particular Eiger disaster is on the climbing.com website .

Thanks for the two parts of your post about the Eiger wall, about the death of climbers in the Eiger, it can be said that the desire to win is a wise behavior, according to Mesner, climbing Bonn, the risk of death is not the risk of climbing, but I am not looking for death, thank you