A short history of dying on the Eiger

Heading up the railway towards the Eiger’s Mittellegi Ridge, while looking down its dreaded North Face. [3600 words, 15min

Once every couple of months I shall be posting a piece longer than my standard ‘trying to keep it down to 1000 words’, and extending over two Wednesdays. This is Part I, and will mostly be about the fatal 1936 attempt on the Eiger. Part II, next week, will be about David’s and my non-fatal ascent of the same mountain by its Mittellegi Ridge. (If this longer post gets truncated when arriving as an email, click ‘view online’ above instead.)

Mistah Kurtz—he dead

TS Eliot, 'The Hollow Men' (1925) epigraph, quoting Joseph Conrad Heart of Darkness1

I'd been working all day on a roof – cutting slates and punching holes for the nails, setting V-shapes of red sandstone along the ridgeline – with two friends from the Mountain Bothies Association. For the evening's entertainment, one of them brought the DVD of The Beckoning Silence: the dramatised documentary about the Eiger made by Louise Osmond and released in 2007, following Joe Simpson's book of 2002.

Outside, moonlight glittered on the Solway, and a little snow lay across the granite hump of Cairnsmore. On the screen, an improbably sharp ice-capped ridge rose out of cloud, and I mentally charged Louise Osmond with lazy film-making for using some stock shot of Patagonia. But then the mountain spun round under the helicopter, to show the big, black, semi-elliptical North Face that's as familiar to mountaineers as the face of any human acquaintance or enemy. Louise Osmond had indeed been showing us the Eiger. And that implausible rock-ridge, rising like a clothes-line through the sky: that was the Mittellegi. I ought to know. In 1971, I climbed it.

Mittellegi Ridge of the Eiger, seen from an aeroplane (photo: Kate Szpek)

You travel to the base of the Mittellegi by underground railway. A tube train is a tube train, whether it's under London or inside the Eiger. You jolt along in the darkness, with nothing to look at but the passengers opposite. On the Eiger's Jungfraujoch railway, those passengers are dressed not in business suits or jeans but in shorts and bright tee-shirts. Also, the front end of the train is steeply tilted upwards. These are two clues that you are not passing underneath the Thames on the Bakerloo Line.

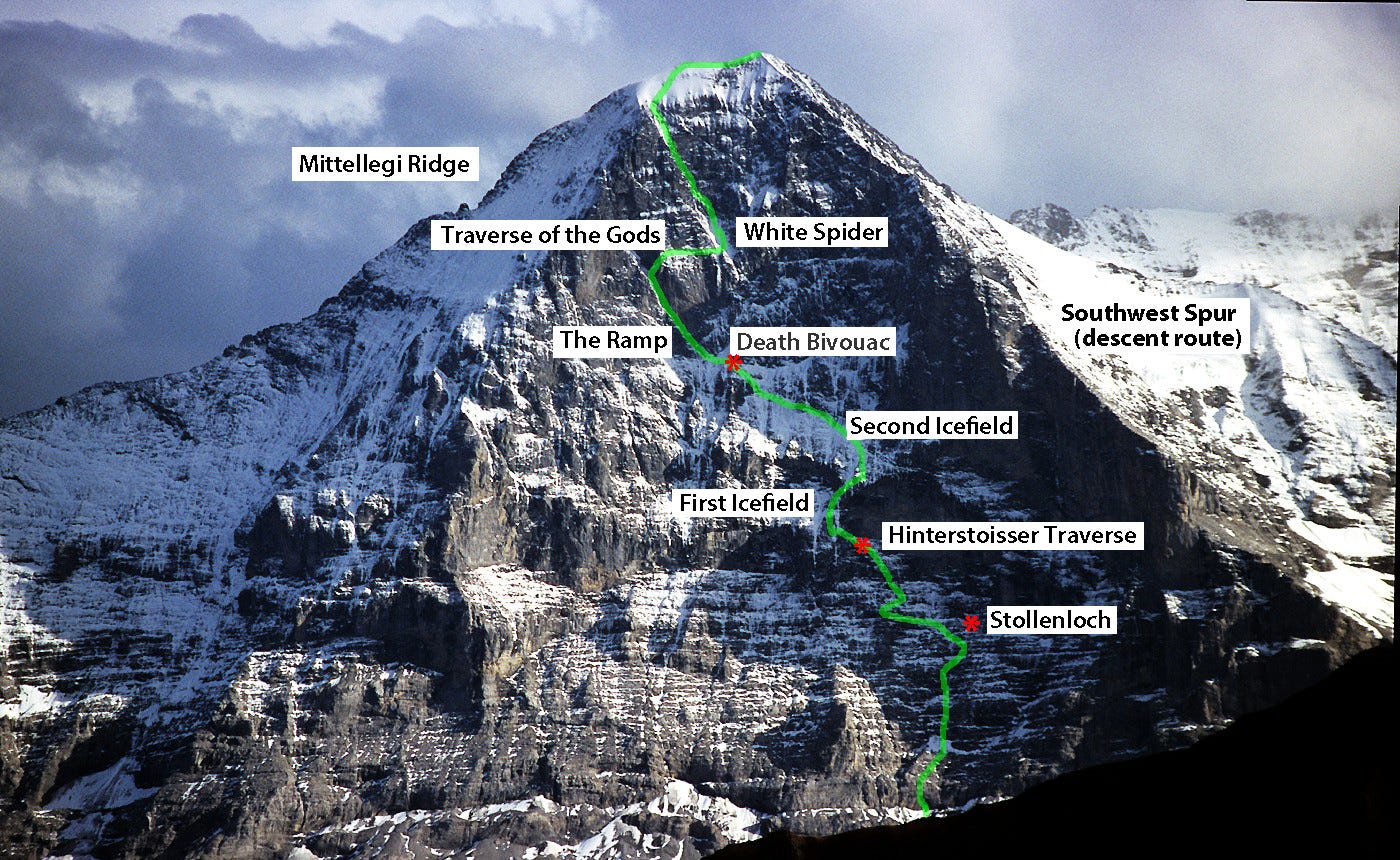

After ten minutes of darkness, a flash of daylight on the left marks Kilometre 3.8, the Stollenloch hole used, while the tunnel was being built, for ejecting rubble over the Eiger's north face. That exit point to the heart of the Eigerwand played an important part in the story of the face and its early climbers. I don't remember even noticing the flash of daylight.

After another ten minutes, the train pulled into a dim platform and the doors opened. Leaving our rucksacks and iceaxes on the cushioned seats, we raced down the platform and a concrete tunnel beyond, to a wide window of scratched and dirty plate glass. We looked out onto the North Face of the Eiger.

On either side, smooth compact rock in sombre dark grey. Pressing our foreheads to the damp glass, we looked down more rock; and every twenty metres or so, a ledge. Each ledge was banked up with steeply angled, dirty ice. The ice had gravel in it, and small stones. Far, far below the lowest icy ledge, the scree at the foot of the face appeared flat and level, although we knew it wasn't. Below and beyond the screes were grey fields, and roads, and the roofs of chalets.

We were very, very happy to be on the inside of the glass.

Eigerwand station, seen from the outside

The Eigerwand – the 'Ogre-wall' or North Face of the Eiger – has to be the earth's most familiar mountain face. World-wide, as many people can recognise the North Face of the Eiger as can identifity the face of a C-list human celebrity such as Pete Buttigieg or Khloé Kardashian. The Eigerwand is 2000m high, which is three times the crags of Ben Nevis that are the UK's largest. It is steep; four patches of high-angle ice are the only interruptions to its precipice. It is also very visible. It forms part of the northern escarpment of the Bernese Oberland: the northern escarpment, in effect, of the Alps. A climber on the face may be hours or days of hard, hard climbing away from the rest of human kind. But he or she looks down on those chalet roofs, and hears the cow bells in the meadows, the two-tone howl of the postbus. And down in Kleine Scheidegg, on the hotel terraces, the climber’s friends and anybody else who's interested can watch the lives of the climbers. And, more interestingly at least to the tourists, their deaths.

To die in the mountains used to be to die in private. Today, on Everest at least, that is no longer so. Forty mountaineers passed along the path to the summit as David Sharp died in a snow cave in 2006. Rob Hall, trapped in the snowstorm with a dead companion, spent his final hours talking to his teammates and fiancée on the satellite phone. And on the Eigerwand, in the 1930s and 1940s, they died in full view of the telescopes of the Bellevue Hotel.

And die they did. Of the first ten to attempt the climb, no-one got to the top of it. Two retreated safely from the centre of the face. The other eight died. The Italian Stefano Longhi, in 1957, survived through five days and nights on a ledge above the Traverse of the Gods, his last words – fame! freddo! (hungry… cold) – heard by helpless rescuers on the nearby West Ridge. His frozen body stood there for two years, before an avalanche carried him down.

The Eigerwand has been – in Europe, at least – uniquely high, and steep, and difficult. It is also uniquely dangerous, in ways the climber's skill can have little influence on. When afternoon sun hits the top of the face, stones come tumbling off the mountain. They funnel down across all four of the icefields, which they cross at roughly a hundred miles an hour with a zipping sound like large bits of cloth tearing; and leave a smell of sulphur. The standard route up the face goes right across each of the four stone-swept icefields.

Then, there is the weather. Because the face is the first rampart of the Alps, storms envelop it suddenly and with ferocity. In less than an hour, loose snow is avalanching continually down the centre of the face, and sweeping clean those four icefields. It could be worse. If the storm brings a warm front, rain rather than snow can fall on the face. Landing on pre-frozen rocks, it forms a layer of black ice over every hand and foothold.

Nowadays, climbers avoid the stonefall (while increasing the avalanche risk) by climbing the North Face in winter, taking advantage of modern winter clothing and front-pointing techniques, as well as reliable five-day weather forecasts. There is also, now, the possibility of helicopter rescue from the face. [An acount of climbing the North Face nowadays is here on UKclimbing.com . ] For a comparible level of danger today you’ll need to go to the Himalaya or Andes.

And yet, the real reason why all climbers know the Eiger – the reason why David and myself, who have neither the desire nor the skills and equipment to die up there, know all the detail of the Difficult Crack, and the First Icefield, and the Second Icefield, and the Death Bivouac, and the Ramp, and the Traverse of the Gods – is down to something as simple as a book. That book takes its name from the highest and steepest of the four icefields: The White Spider. It was written by Heinrich Harrer, one of the four who made the first successful ascent. It wasn't even particularly well written. It doesn't need to be. It sells on its story.

The short life of Toni Kurz

The career of Jesus was told four times. The deaths on the Eiger have been recounted at least a dozen times over. From The White Spider onwards I find it five times on my own shelves and, according to Joe Simpson, he has it twelve times over on his. Those twelve are now joined by his own The Beckoning Silence, and most recently the DVD we viewed at the roof-slating party.

Opera abridges: Verdi leaves out most of Shakespeare's Macbeth for the sake of emotional intensity. It's the same with dramatised documentary. It concentrates (as Simpson's original book does not) on the sixth person to die on the Eiger, 23-year-old Toni Kurz, from Berchtesgaden in Bavaria.

In 1936, with another 23-year-old Bavarian called Anderl Hinterstoisser, he set off up the Eigerwand. They climbed the ledges and broken rocks of the lower face for several hours to the foot of the first steeper section, the Difficult Crack. There they met two Austrians, Edi Rainer and Willi Angerer, also engaged on the climb. The two parties decided to climb together, and Hinterstoisser led off up the Difficult Crack.

Toni Kurz (left) and his friend Anderl Hinterstoisser

The year before, two more Bavarians, Max Sedlmeyer and Karl Mehringer, had taken the lower part of the face direct, up the walls and ledges which we'd looked down on from the railway station inside the mountain. They’d taken a full day of climbing, exposed to stonefall for almost all that time, just to reach the lowest of the four icefields. Hinterstoisser had a better idea. He led off slantwise, up to the right of the main central scoop. This was a much safer line, but eventually led to the base of a huge overhanging wall, the Rote Fluh.

Now it was necessary to climb sideways – to 'traverse' – back left across a steep and featureless wall. If that could be achieved, then a system of cracks, already spotted through the hotel telescopes, would lead upwards again to the corner of the First Ice Field. Hinterstoisser, a brilliant rock climber, achieved the blank wall by a manoeuvre called a tension traverse. In the absence of proper holds, leaning against a rope held from behind allows the use of vertical wrinkles for forward progress. Doubling one of their two climbing ropes through the eye of a piton allowed the other three to cross. The doubled rope could now be retrieved simply by releasing one end and pulling through on the other.

However, the tension traverse is a one-way manoeuvre. Depending on the lie of the crag, it might or might not be possible to recreate the effect in the other direction. What did they think as they let go the rope end and started to pull? In all accounts of the climb, this is a moment of dire significance. As Heinrich Harrer put it in The White Spider: "If it came to a retreat the door was locked behind them."

And as Harrer, himself an Eiger climber, continues: "But who was thinking of a retreat?" The likely truth is, not Karl and not Max. They could have carried up a spare rope to leave across the traverse. But on a climb like the Eiger, the only way to diminish the danger is speed: speed across the stone-swept slopes, speed before the weather changes. Spare rope is heavy, and slows you down; and so, spare rope is stupidity.

If they felt anything at this irreversible moment, it will have been simple relief. On a climb like the Eiger, there’s a constant debilitating doubt. How serious are the dangers ahead? Does it make sense to go on upwards: should we sensibly be turning back? They pulled through the ropes on the Hinterstoisser Traverse; and from then on, they could stop worrying about all that. Upwards was the only way.

It was now afternoon, and stones were hurtling down onto the First Icefield, bouncing briefly, and vanishing into the empty air below. Cutting the tiniest steps possible in the dirty grey ice, moving as fast as they dared, they slanted upwards under the stonefall.

One of the Austrians, Willi Angerer, was struck on the head. But his companions held him on the rope. He was able to continue upwards to the top of the icefield, where the rockface above gave shelter from stones. There they dressed Angerer's wound, and there they spent the night.

On their second day of climbing the group, escorting the injured Austrian, made much slower progress as they worked their way up the gully called the Ice Hose (Eisschlauch) and onto the Second Icefield – steeper than the first one by 5°, and like it, swept by stonefall. Above the Second Ice Field is a buttress called (because of its triangular shape as well as, naturally, its flatness) the Flatiron. At its top is a ledge sheltered from stonefall. It's a place whose safetly is only relative; it is, in fact, where the previous climbers Sedlmeyer and Mehringer spent a week an incessant blizzard, trapped by avalanches both above and below them, until at last they died.

However the Hinterstoisser party stopped short of this Death Bivouac, and spent their second night at the top of the Second Icefield. This was, simply, much too slow. But in their favour, the weather was still clear and cold. The hope had to be that the injured man would make an overnight recovery, and that they could pick up the pace the following morning.

And that hope seemed, to the watchers at the telescopes below, to be fulfilled. As sunlight crept up the snowfields opposite (but not, of course, onto the perpetually shaded North Face itself), the climbers moved strongly up the face of the Flat Iron. But only two of them. The two Austrians below were in retreat, descending the icefield. And soon their two friends turned back to join them.

Slow as they had been the previous day, this third day achieved no more than simply reversing that route. The third night passed at the top of the First Icefield, back at the bivouac of their very first night on the face.

The Mönch (snow-covered), the Eiger, and me rummaging in a rucksack, while climbing the Wetterhorn a couple of days before. Mittellegi ridge runs towards the camera, the North Face in profile on the right. Photo: David Howard

And now the weather went bad on them. Clouds rolled in from the north, swept down across the face, and it started to rain. It’s hard to imagine the misery of that night on the ice, crouched on tiny ledges they’d carved with their iceaxes, soaking wet, hungry, and bitterly cold. And knowing, all night long, that the rocks were icing over, and reducing even further any chance of reversing the tension traverse they'd achieved so cheerfully three days before.

All the following morning, Hinterstoisser, one of the most brilliant climbers of his generation, tried to do it. With the rock holds facing the wrong way, with the rocks themselves ice-covered, with a blizzard raging across the face, it could not be done.

On the way to their deaths the previous summer, Sedlmeyer and Mehringer had climbed to this point from directly below, straight up the centre of the face. That route, swept as it was by stonefall and now also with near-constant avalanches of fresh snow, was the only way left.

Two small points were in their favour.

Firstly: there was no need to go down all the way. A dozen rope-lengths below, ledges ran across the face to the Stollenloch, the refuse hole leading in to the shelter of the railway, a couple of hundred metres down the tracks from where David and I had looked down the face from the train station.

Secondly: the escape line was straight down, and so there was no requirement for climbing, still less for the complex manoeuvring of the tension traverse. They would use the technique of the doubled rope called the abseil. A piton is hammered into a crack. The doubled rope is passed through an attached snap-link and dangles down the face. A climber of today will then attach an abseil device to their climbing harness and thread the doubled abseil rope through it. You then walk backwards down the mountain face. With one hand you pay the abseil rope through the device attached to your harness, and thus control your descent. Provided the anchor at the top holds, the only thing thing that can go wrong is if you accidentally descend off the bottom end of the abseil rope. To prevent this, before throwing down the abseil rope you put a knot into its bottom end, which, if you get that far, will jam in the abseil device.

The climbers of 1936 had no harness: they used a thin hemp line, passed six or eight times around the waist and tied with a reef knot. They had no abseil device. Instead, their technique used their own bodies. The doubled abseil rope passes under the left thigh, then diagonally up across the chest and over the right shoulder. It then passes back under the opposite armpit and is grasped in the left hand. Paradoxical as it seems, in this position the body supports the rope and the rope supports the body. With wet or frozen hemp ropes, the main difficulty can be to overcome friction and achieve any downwards motion at all.

The first climber descends to a suitable ledge, supposing he can find one. He disengages from the rope and his companions descend to join him. They pull down one end of the rope, abandoning the piton and rope sling above. They then search for, and with luck find, a suitable anchor point from which to continue the process.

For the ‘Beckoning Silence’ film, local mountain guides played the roles of the climbers of 1936.

During the afternoon the weather cleared enough to let the watchers below see what was going on. News travelled up the railway, and a railwayman stepped out though the Stollenloch Hole and called up the face.

"All's well!" came a powerful shout, apparently from just above. The railwayman went back inside the mountain and put the kettle on.

But the weather closed in again, and the kettle moved to the stove edge, and simmered long. Two hours later, the railwayman called again. This time he heard only a single voice, screaming for help.

What seems to have happened was this. Having completed several abseils, the party was together on a ledge about 50m above the level of the Stollenloch, and Hinterstoisser would have unroped from the other three to look for the next anchor point. Don't imagine the ledge as any sort of level projection. It would be sloping, narrow and irregular, loose rock and stones covered in loose snow. At this point stonefall, or more likely a powder snow avalanche, swept over them. Hinterstoisser was carried into space. Kurz and the injured Angerer were also swept off the ledge, but they were still roped to Rainer. Their weight pulled Rainer up against the belay point, where he would have frozen to death or, more mercifully, suffocated as his waistlength compressed around his ribs.

A few hours later, rescuers who had come out through the Stollenloch onto the face were able to see Kurz as he dangled from the rope above them. Hanging below Kurz, but still out of reach of the rescuers, Angerer was now also dead.

Toni Kurz’s fall, re-enacted for the film ‘The Beckoning Silence’ – from the ‘making-of’ video

The rescuers were ordinary Swiss mountain guides (who, incidentally, had been forbidden by the authorities from attempting any rescues at all on the lethal Eigerwand). Even with the skills of a Hinterstoisser, they could not have climbed the iced rocks to Kurz and the two corpses. And night was now falling. They comforted Toni Kurz as best they could. Then as his despairing cries echoed around the crags they retreated into the tunnel.

During the night it froze, hard. As Kurz hung from the rope, icicles 20cm long formed on the spikes of his crampons. But when the rescuers returned, he was still alive.

And the rocks were still iced; if anything, even more thickly. They could no more reach him now than the previous evening. Could Kurz not abseil down to them?

Kurz could not. He was already at the end of his rope. He was deeply hyperthermic, barely able to move even his lips to cry. During the night he had lost a mitten, and his right hand was now frozen to a useless claw. Patiently, carefully, the rescuers explained what they required of him.

The first stage was to cut the rope below him. Angerer's body was now untied; it had frozen to the rockface and did not fall. Next, Kurz was to climb, one handed, back up the rope to the ledge where Rainer's body stood clamped to the rockface. Somehow, numb and one-handed, Kurz achieved this.

But that was just the start. The rope that had joined him to Rainer was three-stranded. With one gloved hand and his teeth, he unravelled the three strands. After five hours of painful labour he had made a cord, too weak for climbing, but long enough to lower to the guides below. With this, he could haul up a small rucksack of pitons, food, water, and the end of a fresh climbing rope. Even the new rope was not quite long enough, but fortunately the guides had a spare which they knotted onto it just before it lifted out of their reach.

Finally, Kurz was ready to start his descent. No need for a doubled rope: he simply tied the top end into the belay and arranged it around his body in the abseil position. Because he would have only his left hand to check the descent, he took an extra precaution. Before putting his weight on the abseil rope, he passed it, for added friction, through a snap link clipped to his hempen waistlength. The abseil rope would now support him at both leg and waist, and the gentlest hand pressure would serve to check his descent. He started down.

Below, the rescuers watched the rope as it jerked under his weight above. After an age, his head and shoulders appeared at the break of the slope. The last part of the descent, immediately above their ledge, was overhanging, with the rope dangling free to the hands of the rescuers. But Kurz was accustomed to abseil overhangs. As his feet parted from the rockface and he hung free in space, he continued downwards in slow jerks as the free rope passed through his downward-reaching left hand.

And then his fingers, reaching down, found the knot joining the two ropes. The knot came up over his shoulder, down across his chest, and jammed against the snap-link at his waist. He could descend no further.

Reaching up, the rescuers could just touch Kurz with their iceaxes. They might just as well have been in the valley 1000m below. They urged him to find some way of getting the knot past the obstacle. There was no way. And Kurz, finally, was through. Quietly, he told them: "Ich kann nicht mehr" – I can do no more. And he died.

Heart of Darkness was published in instalments in Blackwood’s Magazine 1899 – the same source that covered the seven railway surveyors on Rannoch Moor who I described last week. Conrad’s ‘Mistah Kurtz’ dies after an obsessive river-boat trip up the Congo River; so Toni Kurz and Mista Kurtz are re-pointing the correspondence between mountaineering and adventures in boats that I wrote about at the start of January.

Fascinating stuff. My connection with the Eiger isn't as impressive as climbing the Mittelleggi (but I do remember that view from the summit of the Wetterhorn). That was 1991, I think. My second visit was in 2013 on a press trip marking the 75th anniversary of the FA of the face. We got to see some of the original gear in the museum in Grindelwald, we rode the railway and looked out of those windows, and we had a bivouac on top of the Rotstock, which would be a major crag by UK standards but here is just an afterhtought tacked on to the side of the Eigerwand. And then we walked down by the Eiger Trail and had a near miss (near enough!) from a fridge-sized boulder casually shed from the face.

I have just enough of an idea what climbing the North Face would be like to know it was always beyond me.

An interesting and sad story about the epic wall. Thank you for your good posts