Here’s a question. If people climb for the sake of fame and reputation, why don't more of us cheat? We can assume that getting caught cheating is a slightly less bad fate than death. In which case, simple cost-benefit analysis suggests that at least as many of us should cheat too much (and get caught) as overdo the Himalayan 8000m peaks (and die). But in fact, caught cheats are rather rare.

Do climbers cheat? And if not, why not?

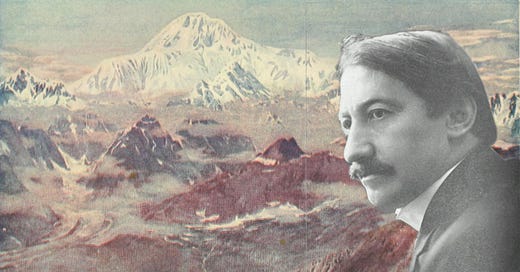

One climber who undoubtedly did fake it was Frederick Cook, who climbed North America’s high-point, 6194m Denali1 – or, actually, didn’t – in April of 1906.

On not doing Denali

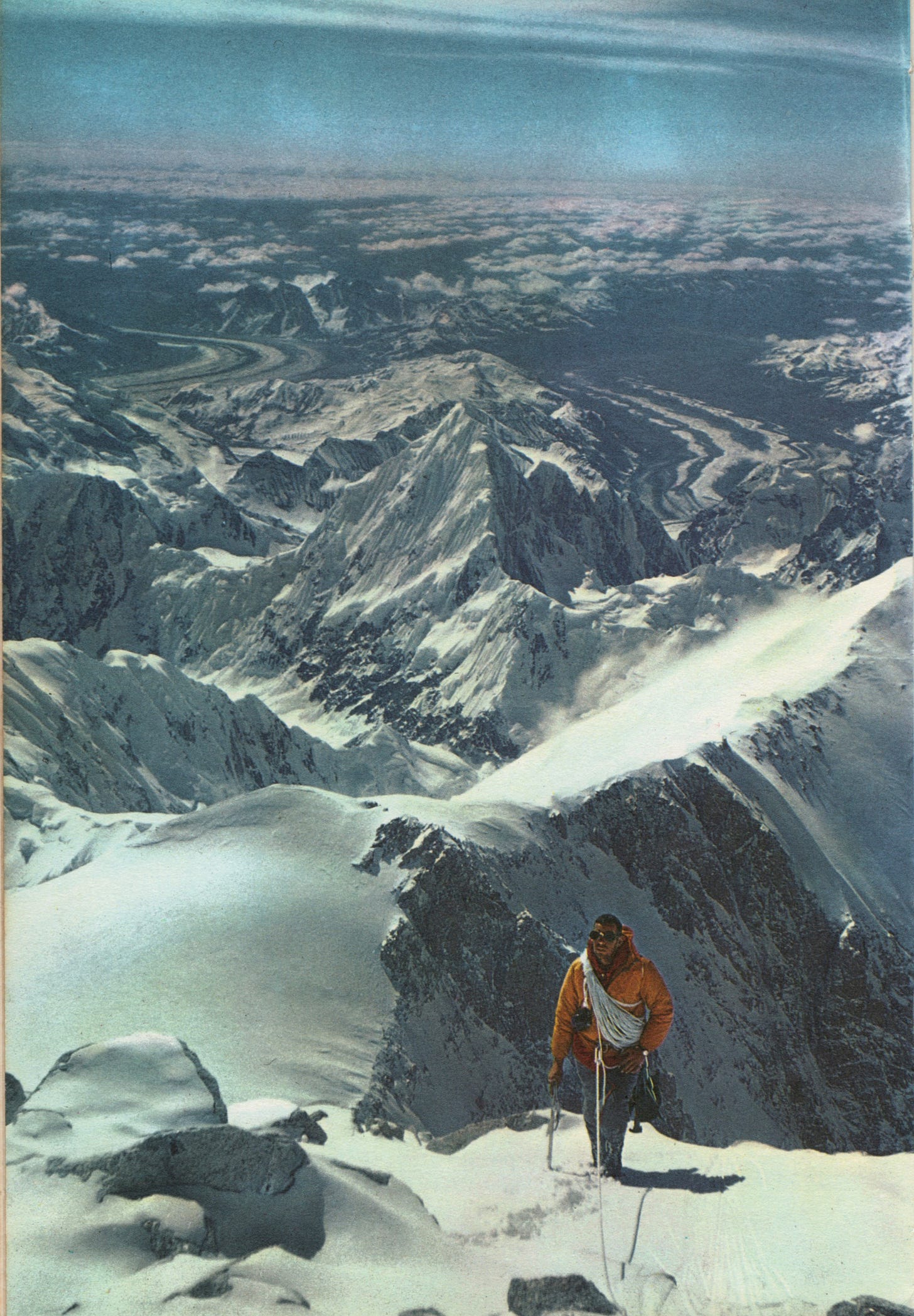

At 20,320ft (they use old-style unites in the US), Denali is only slightly higher than Kilimanjaro. But up Alaska, not far south of th Arctic Circle, it’s a much more serious hill, snow and ice all the way. It was first reached by a non-indigenous person in 1896. This right-wing gold prospector promptly renamed it as Mount McKinley after the Republican candidate in that year’s presidential election.

As President William McKinley went on to raise the highest import tariffs in US history so far. He presided over an industrial boom in oil, steel and electricals, as well as a recession, the Panic of 1893. McKinley waged war on Spain, seized and occupied Puerto Rico, and got assassinated during the first year of his second term.

In 1903 the polar explorer Frederick Albert Cook managed to trek right round the mountain, and climbed it to nearly 11,000ft.

Three years later, he returned with a small team to conquer the mountain.

The mountain climber and the arctic explorer in their exploits run to kindred attainments. The polar traveler walks over uniform snows, over moving seas of wind-driven ice; his siege is long and his main torment is the long winter darkness. The mountaineer reaches heavenward over the shows of cloudland. His task is shorter but more strenuous and his worst discomfort is the task of breathing rarefied air. In the general routine, however both suffer a similar train of hardships, which hardships are followed by a similar movement of mental awakening, of spiritual aspirations, and of profound and peculiar philosophy…. He who ventures into the polar arena or the cloud battlefield of high mountains will long to return again and again to the scene of his suffering and inspiration.2

At the igloo camp at 16,300ft, he writes

For desolation it would strain the English dictionary to describe it, but there are shades of desolation as there are grades of intoxication. Lat night the note of abandon was soul destroying. From out dug-out in the treacherous drop the outlook and the world about us was desperately gloomy. To-night with the sparkle and glitter of the snowy world above the clouds illuminated by glowing start that hang like huge arc lights from a black sky, we see another phase of desolation, one full of hope, inspiration, and promise.

In the lower climb there was a thrill which fired ambitions. The beauty of the naked cliffs raised us to a pitch of ecstasy which made us forte fatigue, but in the upper world all of this was changed. It was a region of harmony in colour and contour. A suffusion of light with subdued colour blends to frosty shades. A softening of contours by a flooding of snow crystals fills theugly gaps and rounds off the sharp corners. But nevertheless it is a region of pulseless eternity wherere the spirits with the clouds fall to earth in weeping sadness.

With a single companion, he continued upwards now on gentler slopes. “We edged up along a steep snowy ridge and over the heaven-scraped granite to the top. AT LAST! The soul-stirring task was crowned with victory; the top of the continent was under our feet. Our hands clasped but not a word was uttered… and then after several long breaths the ghastly unreality of our position began to excite my frosted senses.

The Arctic Circle was in sight: so was the Pacific Ocean. The sky appeared “as black as that of midnight”.

Straight away, Cook’s account was called into question: not least by the other two members of his own expedition. His summit companion Ed Barrill signed various affidavits, after being bribed, separately, by both Cook and the newspapers debunking him.

However, Cook did have the photo evidence to prove it. And the influential Robert Peary, Cook’s commander on his earlier expeditions, also backed him up. Cook had been an effective Arctic explorer. During their unexpected icing-in over the Arctic winter, Cook had saved the crew from scurvy by shooting seals. (And never mind that, in his next expedition to Tierra del Fuego, he’d tried to publish his companion’s dictionary of the native Ona Yahgan language as his own.)

Robert Peary would come to regret his support. When Peary emerged from the Arctic in 1906 after his own expedition to the North Pole – he was surprised and upset to learn that Cook had emerged from the Arctic a few months before, claiming to have got there a year ahead.

So did Fred Cook really do Denali? Maybe he did and maybe he didn’t, but actually, no, he didn’t. His descriptions stopped matching the actual terrain 15km from the summit. The Pacific isn’t visible from Denali. The Igloo Camp didn’t happen, and the ‘summit’ photo was taken on a much smaller peak 30 km away: the 5338ft ‘Fake Peak’ as it’s now known.

He also didn’t do the North Pole.

The writer Robert Bryce, quoted on Cook’s Wikipedia page, suggests that Cook "genuinely loved and hungered for the real meat of exploration—mapping new routes and shorelines, learning and adapting to the survival techniques of the Eskimos, advancing his own knowledge—and that of the world—for its own sake”. And that he only did (or rather didn’t) Denali for the necessary sponsorship money.

Later on, poor Frederick Albert would be jailed for 7 years for oil company fraud – out of a full sentence of 14 years, which seems a lot just for paying dividends out of stock rather than profits. (When Thames Water did something rather similar, they got cash bonuses.) He eventually got pardoned by Franklin D Rooseveldt.

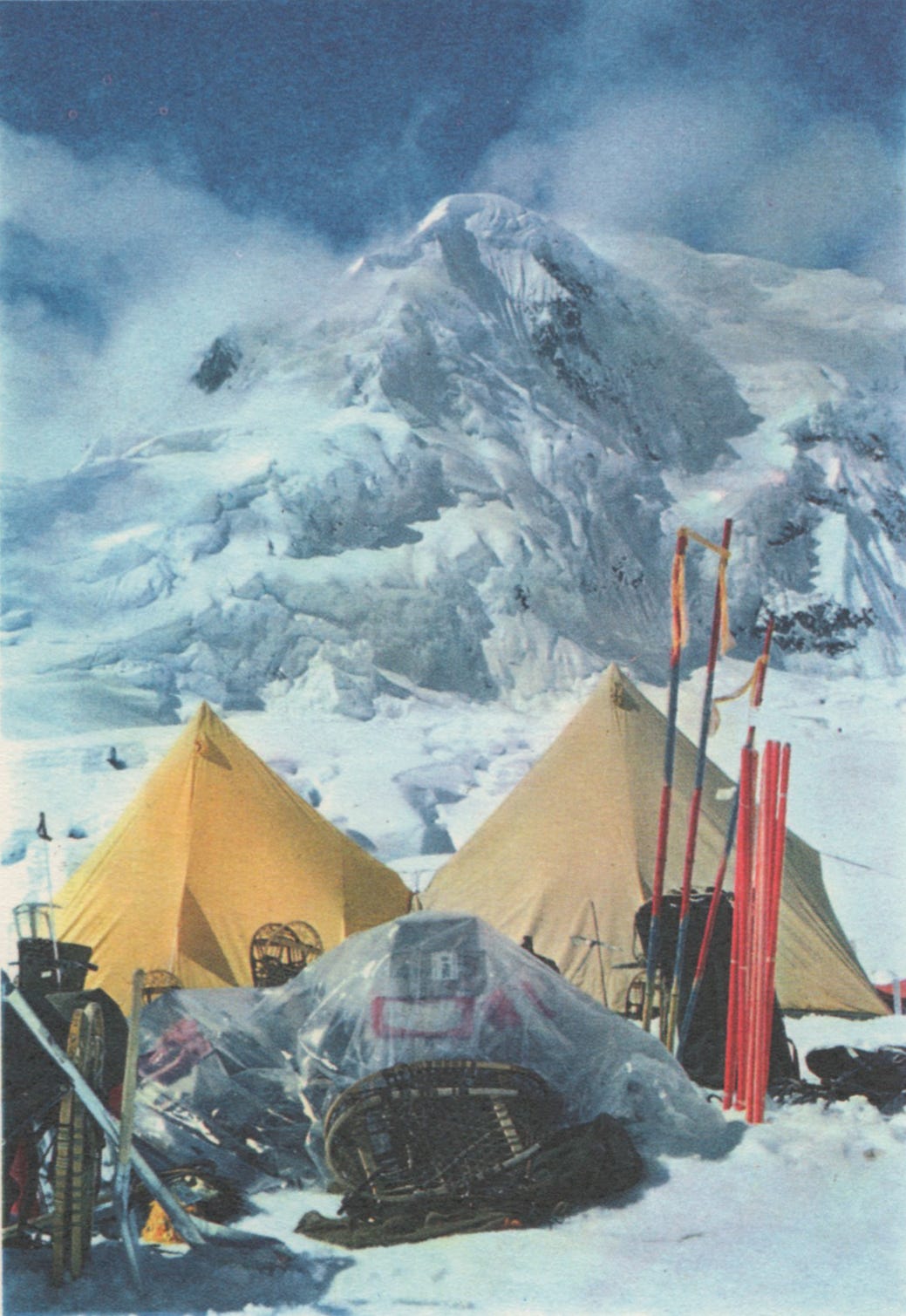

Meanwhile, when Cook’s cooked book reached the saloons of Fairbanks Alaska, a group of prospectors were so annoyed by its ridiculous claims that they decided to go and climb the thing themselves. With no mountaineering experience but sponsorship from two local saloon-keepers and a first rate dog team, Tom Lloyd, Billy Taylor, Pete Anderson and Charley McGonagall sledded 150 miles to the mountain. Billy, Pete and Charley then climbed it in three days and two nights of continuous effort. They planted a 14-foot flagpole on North Peak, and returned to widespread disbelief. At least until their flagpole was spotted by independent observers three years later.

They’d made one unfortunate mistake. It’s the South Peak that’s Denali’s true summit.

Yes, I have noticed that the new president of the US has just changed the official name of the country’s high point. But you know what? The English language does not belong to Donald J Trump.

To the Top of the Continent: Discovery, Exploration and Adventure in Sub-arctic Alaska: The First Ascent of Mt. McKinley, 1903-1906, by FREDERICK A. COOK, M.D. Author of “Through the First Antarctic Night” Chevalier of the Order of Leopold I. Member of the American, National, Philadelphia and Bengian Geographical Societies President of the Explorers Club (New York, 1908) is on the Internet Archive .

Great story. Thanks especially for footnote #1. A lot of us over here agree.

It was an interesting topic, thanks.