A study in Skiddaw

Skiddaw, England’s 4th-highest hill, is about to become its highest nature reserve. [1500 words 6 mins

This week, the Cumbria Wildlife Trust has a chance to buy up 12 square kilometres of Skiddaw, England’s fourth highest hill, to convert it into England’s highest ever nature reserve. Aviva’s already offered them £6 million – well, that represents just a small share out of the annual charges on my pension plan. The remaining £1.25m needs to be raised from us, the public.

When the English Lake District was elevated to UNESCO World Heritage status in 2017, it was as an ‘evolving cultural landscape’. And so, while the Wildlife Trust will be planting some ancient Atlantic oakwood and montane scrub, and sabotaging the drainage to bring back the bog – it’s also appropriate to celebrate Skiddaw for its status as an English cultural high-point, up there with Morris dancing, brass bands, and the art of Charli XCX.

As recently as 280 years ago, Skiddaw was still a huge and frightening mountain. One visitor to the Caldbeck fells recorded “insuperable precipices and towering peaks, and landscapes of a quite different and more romantic air than any part of the general ridge [presumably the Pennines] and of nearer affinity to the Switzerland Alps.” (‘A Journey to Caudebec Fells’, Gentleman’s Magazine 1747)

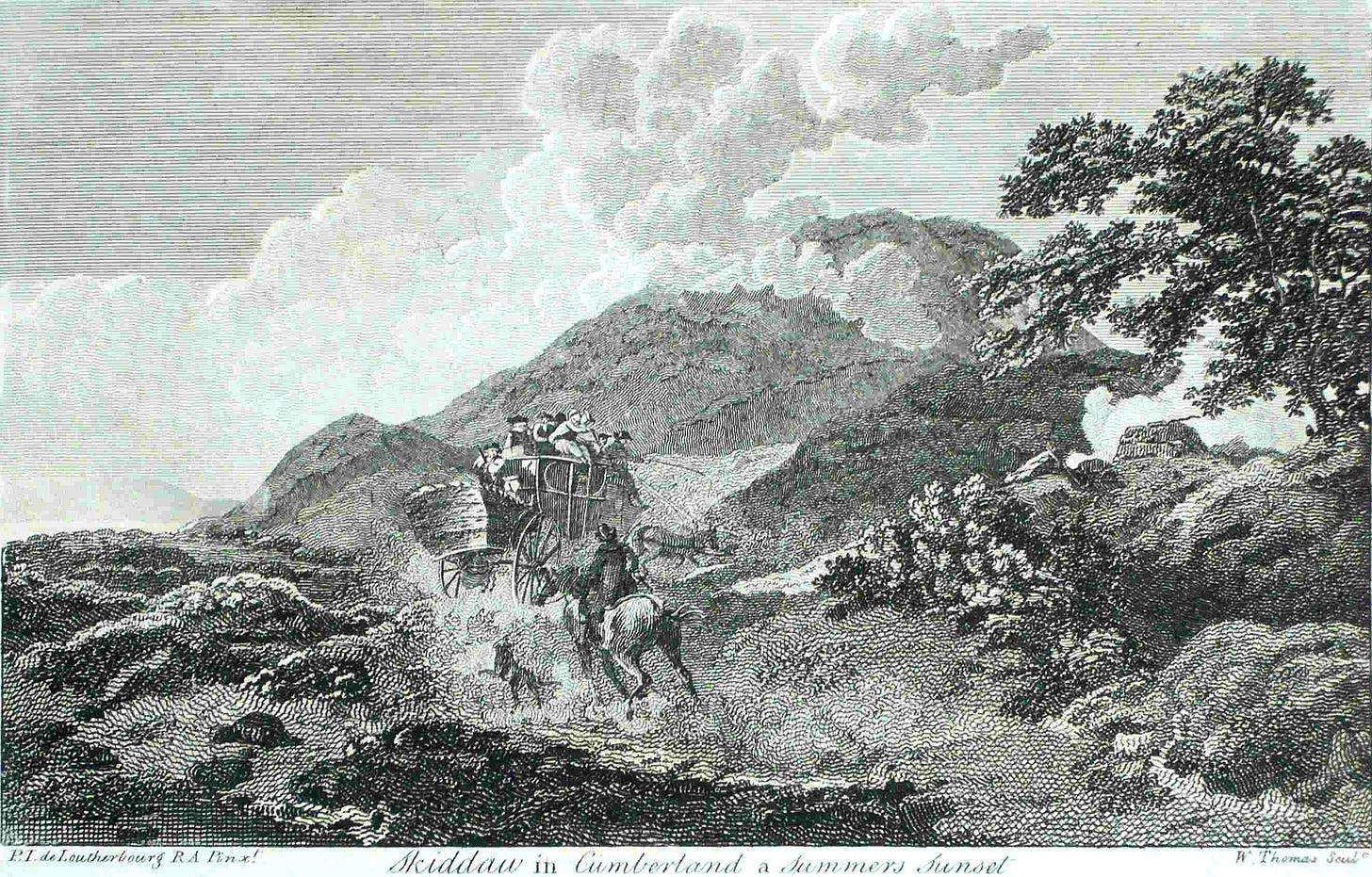

Despite these terrors, from about 1750 the ascent of Skiddaw from Keswick was the standard hill adventure for the braver sort of wild traveller. Guiding such expeditions was a nice little money-earner for the Skiddaw shepherds, though they must have been amazed at the fuss their clients made. It was customary to suffer from vertigo, while altitude sickness usually set in about the 2500-foot mark.

The outdoor writer William Hutchinson had a great time on the hill in 1773. Already suffering the usual effects of altitude (“respiration seemed to be performed with a kind of asthmatic oppression”) he was attacked by all the fury of the elements.

The clouds advanced with accelerated speed: a hollow blast sounded amongst the hills and dells which lay below, and seemed to fly from the approaching darkness.

We were rejoicing in this grand spectacle of nature, and thinking ourselves fortunate in having beheld so extraordinary an event, when… a violent burst of thunder, engendered in the vapour below, stunned every sense, in horrid uproar. The mountain seemed to tremble... our guide lay on the earth terrified and amazed, in his ejaculations, accusing us of presumption and impiety... to descend, was to rush into the inflammable vapur from whence our troubles proceeded, to stay was equally hazardous.

William Hutchinson’s Excursion to the Lakes in Westmoreland and Cumberland in the years 1773 and 1774, published 1776

Eventually, like many a traveller of today, “we descended the hill wet and fatigued, and were happy when we regained our inn at Keswick.”

The novelist Mrs Radcliffe was an early explorer of the Alps (see my post back in August). She climbed Skiddaw in 1797 and complained of the thinness of the air – one of the very last to do so. Perhaps the thickening of the atmosphere due to the industrial revolution finally let people cross the 900m mark without ill effects. And by 1830 it was a suitable ascent for an eleven-year-old. The precocious lad John Ruskin recorded his ascent in verse:

How frowned the dark rocks which, bare savage and wild,

In heaps upon heaps were tremendously piled!

And how vast the ravines which, so craggy and deep,

Down dreadful descending divided the steep!

John Ruskin ‘Iteriad, or Three Weeks Among the Lakes’, 1831

Cumberland poet Norman Nicholson considers this as bad verse, even for an eleven-year-old, but commends Ruskin for seeing Skiddaw reasonably accurately. Perhaps Nicholson is just envious of that thumping alliteration.

Setting Skiddaw alight

“The red glare on Skiddaw roused the burghers of Carlisle”

It was Baron Macaulay, in a poem learnt by generations of Victorian schoolchildren, who described the chain of beacons, from London to the Scottish Border, that warned England of the Spanish Armada in 1688. The line is quoted both by Wainwright in his ‘Pictorial Guide’ and by Arthur Ransome in one of the Swallows & Amazons books.

Signal fires were routinely used in Lakeland to warn of marauding Scots. However, historians who are also hillwalkers think these would be set at lower points, such as High Rigg or Latrigg. It takes even a fit firelighter an hour and a half to climb Skiddaw, by which time the Scots would have beaten down the door of the cowshed and headed off home. Also, the summit of Skiddaw is quite often in cloud.

Despite what I’m about to say about the pleasures of Skiddaw in the dark, the Mayor of Keswick didn’t fancy that experience, and at the start of 2000 the Millennium Beacon was fired up down on Latrigg. However, a more authentic beacon fire was alight on Skiddaw summit 22 years before, at Queen Elizabeth’s Silver Jubilee. Despite its being 6th June, the firelight shone down on several centimetres of snow. The watchfire was part of a chain from Land’s End to the north of Scotland. From Skiddaw on a clear night you can easily see fires on Cross Fell southwards and Lowther Hill in the north; from Lowther you can see Ben More in Perthshire; from Ben More, Ben Nevis...

Disappointingly, though, they didn’t see anything at all. The cloud was down, and it was raining.

There was better weather for the bonfire lit on Skiddaw’s top on 21st August 1815 to celebrate the victory at Waterloo. Among the crowd was poet laureate Robert Southey1 along with future poet laureate William Wordsworth in a red cloak borrowed from Mrs Southey.

We roasted beef and boiled plum-puddings there ; sung 'God save the King' round the most furious body of flaming tar-barrels that I ever saw ; drank a huge wooden bowl of punch ; fired cannon at every health with three times three, and rolled large blazing balls of tow and turpentine down the steep side of the mountain. The effect was grand beyond imagination. We formed a huge circle round the most intense light, and behind us was an immeasurable arch of the most intense darkness, for our bonfire fairly put out the moon.

In the excitement, someone kicked over the hot water for the rum punch. Attempting to sneak away, the culprit was identified by his unwieldy red cloak. Appropriately, Wordsworth was mocked in bad verse:

Twas you that kicked the kettle down !

'twas you, Sir, you !

Flaming torches marked the path back down. All arrived safely at Keswick by midnight, even the fellow so drunk he descended on horseback facing backwards. The lively account of the event is from Robert Southey's letter to his brother Henry a few days later.

Wordsworth got his revenge on the hill, by writing it up in his sonnet starting 'Pelion and Ossa'.

What was the great Parnassus' self to Thee,

Mount Skiddaw? In his natural sovereignty

Our British Hill is nobler far ; he shrouds

His double front among Atlantic clouds,

And pours forth streams more sweet than Castaly.

Showing that whatever we think of Robert Southey, Wordsworth could write worse.

The greatest wind speeds are recorded on rounded mountains, and Skiddaw rivals Cross Fell for the title of windiest spot in England. Standing apart from the main Lakeland mass, it probably also has England’s biggest view.2 Southwards you see all of the rest of Lakeland – even the Coniston fells are just visible over Little Man. Eastwards, Cross Fell and the Northern Pennines are across the Vale of Eden. Just across the Solway stands the rounded double hump of Criffel, a granite hill near Dumfries. Behind it are the hills of Scotland, from the Southern Uplands across to Galloway.

Westwards, the Isle of Man is a mere 60 miles away (100km), and will be seen on any clear day outside the hazy heats of Summer. Grey shapes along the horizon beyond are the north of Ireland, with Slieve Donard, 117 miles away, as their most distant point. The viewpoint indicator is disappointing, mentioning only a few points and those at no great distance. Skiddaw needs a ‘We Want Slieve Donard On Summit Indicator’ pressure group.

The view is even better in the dark. The 200 walkers in the former Ramblers’ Association Four Peaks Challenge used to begin by climbing Skiddaw at two in the morning. Many runners attempting the Bob Graham Round of 42 summits set off up Skiddaw at midnight or 1 a m. These alone are enough to assure Skiddaw the title of ‘most night-climbed hill’. Being rather keen on such activities, of my first six ascents of Skiddaw only two were in daylight. With its wide, easy paths and lack of precipices, it is a good one for doing in the dark.

Take spare batteries and lots of warm clothes.

Yes, that’s the Robert Southey who claims he never walked further than the stone circle at Castlerigg. As the least famous of the Lakes Poets, Southey’s coming up in a future post here some day.

Slightly further than Slieve Donard, 194km, to a corner of Snowdonia southwest of Yr Wyddfa. Glimpsed in the gap between Kirk Fell and Pillar. Take a telescope.

The Skiddaw Forest is the whole eastern flank of the hill, running up to the summit ridge. Here 'forest' means a hunting estate, not implying trees (though the Wildlife Trust is going to turn much of it into a forest also in the sense of having trees). It has been owned by the Earl of Egremont, with the former keepers' cottage and grouse-shooting lodge, Skiddaw House, at one time a youth hostel and then managed by various voluntary bodies. It's now owned by the Wildlife Trust as a non-profit called Esmé has lent it the cash for the time being.

Since the Countryside and Rights of Way Act of 2000 the public has had a legal right of access to the whole hill, though with certain restrictions. In practice, we have had effective access since time immemorial. We still don't have legal entitlement to camp out overnight, but again in practice we can and do.

Great piece. I love how knowledge of cultural history animates landscapes in our time.