William Shakespeare, mountain man

Birnam Wood, a cave in the Brecon Beacons, and a long walk to Milford Haven: from the man who invented mountaineers [1000 words, 4 min

Now for our mountain sport. Up to yon hill.

Your legs are young.

Shakespeare, Cymbeline (Act III scene 3)

Do Shakespeare’s plays have not enough stuff about mountains? Or do they, on the other hand, have too much?

For John Ruskin, “mountains are the beginning and end of all natural scenery”, and given that Shakespeare is the beginning and end of all English literature, that left John Ruskin with a puzzle. How come there aren’t that many mountains in Shakespeare?

In the opposite corner, as it were, stand the Baconians. Or not so much stand as jump up and down waving their arms about and shouting. My father’s cousin was a Baconian; which meant that he directed much intellectual effort to the idea that Shakespeare’s plays were actually written by the courtier and philosopher Sir Frances Bacon.1 Cousin John, as it happens, was also a devotee of crop circles.

Counting mountains: Representative Ignatius L Donnelly [Wikimedia Commons]

Extreme Baconians (I’m citing 19th century US congressman Ignatius L Donnelly here) have worked out that Sir Francis didn’t just write Shakespeare, but also all of Christopher Marlowe, Burton's Anatomy of Melancholy, and Montaigne's Essays – as well as finding time in odd moments to write his own Essays as well. The clue being not the rarity but the extreme frequency of mountains in Shakespeare’s plays. So that, as Romeo in the sex scene warns Juliet that

Night’s candles are burnt out, and jocund day

Stands tiptoe on the misty mountain-tops

the playwright is sniggering in the wings going “mountain, Montaigne, aren’t I the clever little fellow?”

So who’s wrong here, John Ruskin or Congressman Ignatius L Donnelly? Well, according to the Shakespeare Concordance, the word mountain occurs 34 times: twice each in the Sonnets and in Venus and Adonis plus 30 times in the plays, including 10 times in Cymbeline and 5 in The Tempest.

For comparison, the word ‘bacon’ occurs only twice. And perhaps if Frankie B the true playwright had really been inclined to plant secret nomenclatural clues, the line “Hang-hog is Latin for bacon, I warrant you” from Merry Wives of Windsor isn’t exactly the way to do it…

Morning light on Blencathra

Full many a glorious morning I have seen

Flatter the mountain-tops with sovereign eye,

Kissing with golden face the meadows green,

Gilding pale streams with heavenly alchemy.(Shakespeare, Sonnet 33)

Yes, it does sound as if the man from the flatlands of Warwickshire and London's South Bank knew a bit about hills. What’s more, in Highland Perthshire, under the oak trees of Birnam Wood – the wood that the witches in Macbeth make their dreadful prophesy about – there's a faded, paint-flaking interpretation board. And a story, a rumour as delicate as the dew on a dawn spiderweb that’s going to be broken just by picking it up and looking at. According to that interpretation board, at some point during the 1580s a group of travelling players came up out of England and along the River Garry. And yes, in the 1580s, Shakespeare was working as a travelling player. (Perhaps,)2

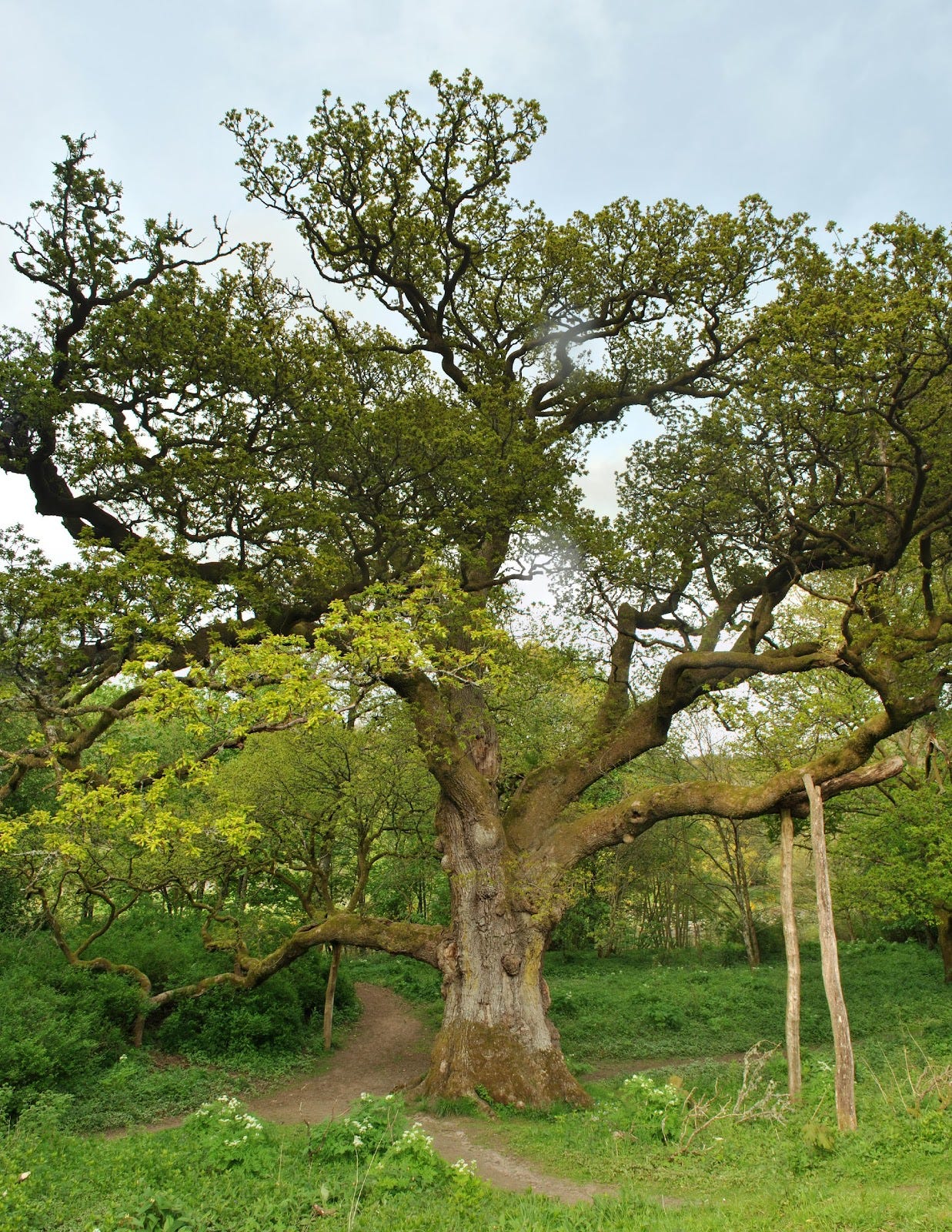

The Birnam Oak, still struggling to get any closer to Dunsinane

So what about these mountaineers? According to Merriam-Webster online, the first use of the word was in 1616, the same year as cockroach, custard, raspberry, shoestring and windproof. But Merriam-Webster is wrong by six years. 'Mountaineer' is one of the one thousand seven hundred English words invented by William Shakespeare. It’s found in his 1610 play 'Cymbeline'.3

Soft! What are you

That fly me thus? some villain mountaineers?

I have heard of such. What slave art thou?

Shakespeare’s meaning is slightly different from today's. The two kidnapped princes, in their Pembrokeshire cave, are mountaineers in that they live among mountains and flourish there. Their 'mountain sport' consists of hunting deer in order to feed themselves and the old man they believe to be their father.

Imogen starts her hike to Milford Haven in unsuitable kit. Painted by J. Heppner, Engraved by: Rob Thew 1801

“Oh for a horse with wings,” cries Imogen, “to fly me to Milford Haven!” though I’ve misquoted her slightly. The lively, cross-dressing princess has got the right idea, although she’s a bit off on the detail. Milford Haven is actually the one bit to skip on the magnificent Pembrokeshire coast. The 300km (186 miles) of it form a national trail around Britain’s second thinnest national park.4 That’s short enough to walk in a fortnight – especially if you sensibly skip Milford Haven.

Cymbeline is one of Shakespeare's 'late romances' (the other three being Pericles, The Winter's Tale and The Tempest). And it’s a late-stage mashup of all Shakespeare’s favourite ideas: heroines who dress up as a boy, jealous husbands with innocent wives, incompetent or oppressive parents, lost offspring, people who betray one another, people who dress up as each other, civilised wilderness set against the cultivated hypocrisy of the court, the inbuilt nobility or otherwise of kings, and those deadly poisons that are actually only sleeping potions. All expressed through a mixture of grotesque violence and the loveliest of iambic pentameters. Along with, yes, a pretty silly storyline.

Because of its daft plot, Cymbeline isn't too often performed – I’ve seen it twice (Edinburgh Festival and Sam Wanamaker Theatre) and both times it didn’t really come off. But it was the Shakespeare play buried in his grave with the poet Alfred Lord Tennyson.

Penguin Shakespeare cover 2008 (Clare Melinsky)

In ancient Britain the King, Cymbeline, has a second wife called, simply, Queen. Queen wants to marry off the King’s existing daughter, Imogen, to her own unattractive son, Cloten. But Imogen’s already secretly married to a person called Posthumus.

So the Queen procures from the court physician a deadly poison. Whom is she planning to do in? Fortunately, the suspicious physician decides to substitute a harmless sleeping potion. Who will disguise herself as what, and who else will disguise himself as whom? Who will take the potion and pass into insensibility? Who will then presume that person dead? And how come everybody ends up in Milford Haven, just where the two lost princes, Guiderius and Averigius are living in their cave up in the foothills of the Bannau Brychyniog or Brecon Beacons National Park? Oh, and the Romans are conveniently invading at Milford Haven as well.5

The boy mountaineers don’t know what to make of Imogen’s unconvincing attempt at cross-dressing. [Painting Henry Singleton]

The first mountaineers, despite their uncouth manners and irregular lifestyle, are shown as pretty sound characters.6 They provide a public service by spontaneously murdering the sexual predator Cloten, offer a tender elegy for the poor lost boy who dies on their doorstep, and leap into battle to defend Britain from the Romans. It helps that they’re lost princes; they do, without realising it, have the blood of kings and queens in their veins.

But in a way, that’s true of all mountaineers. Isn’t it?

In the novel ‘No Bed for Bacon’ (1941) sourcebook for the film ‘Shakespeare in Love’, Sir Francis is constantly interrupting Shakespeare at his workplace asking him, Shakespeare, to touch up his, Sir Francis’s, Essays: a joke against Baconians. The book has other even funnier jokes in it as well.

Most literary historians simply don’t know what Shakespeare was up to in the 1580s. But for those seeking proper academic references, all of this can be confirmed via the sound authority of VisitPerthshire tourist board’s website. Apparently James VI of Scotland asked Queen Elizabeth to send up some of these English comedians he’d been hearing about. (On the other hand, Birnam Wood does get a mention already in Shakespeare’s source material, Holinshed’s Chronicles; so he did already know about the place.)

Unless Merriam-Webster’s man was there listening in the Globe back in 1610, he’d have had to wait for the First Folio to come out in 1623.

The thinnest national park being the Norfolk Broads. Some good walking there too, but very flat. And not much Shakespearean resonance either.

Spoilers: Imogen; Imogen, as a boy of course, she being a Shakespearean heroine; Cloten, as Imogen’s secret husband Posthumus; Imogen again; the two mountaineer princes.

The younger of the two lost princelings, Arviragus, is alternatively named Caractacus: the man who was to become the battle leader of the Silurians. If his cave was just a few miles north of Milford Haven, then it was in appropriate rocks of the Silurian system. So showing that Shakespeare wasn’t just a mountaineer, he was a geologist as well. But either way, he wasn’t Sir Frances Bacon.