Utah and the Line of Beauty

Canyonlands National Park and the shapes of scenery [2100 words 12-15 min

Thelma: [stopping suddenly at the edge of a cliff] What in the hell is this?

Louise: I don't know. I think... I think it's the goddamn Grand Canyon.

Thelma: Isn't it beautiful?

Louise: Yeah. It's something else, all right.‘Thelma and Louise’ dir. Ridley Scott 1991; screenplay Callie Khouri

This is a longer post, for anybody who prefers a gentle essay via Substack to the Christmas season’s more traditional celebrations of consumerism and food. If reading on email, you may need to return to the top and click ‘read in browser’ above.

Backpacking through Utah's Canyonlands means heat, and gravel, and the occasional brown bear. It means wide canyon floors carpeted in purple sage. It means cliffs layered in pink and beige rising above huge curves and hollows of bare red slickrock.

It also means a gallon of water for every 24 hours, to survive in the dry desert air. That water has to be carried on our backs, all the way. There's just one compensation – the US gallon is slightly smaller than our one, so the day's supply weighs in at 8lb rather than 10. Even more usefully, the Salt Creek, running through the same-named canyon, does flow reliably all year round. So we planned to follow it for our first two days: only the third day of water, over lesser canyons and the high bare rockfields, would need to be on our backs.

Well, that was the plan. But then they had a drought. You wouldn't think the dry desert could suffer drought, but they did. Zero rainfall for four months, and the Salt Creek wasn’t there any more.

Compared with the three gallon water load, the other problems seemed minor. The rattlesnakes and scorpions: shrug. The mosquitos: no mosquitos in fact, they don't do droughts either. The bears, yes: maybe also a mountain lion. The bentonite clay.

The bentonite clay? Yes, well. Despite the three months of draught, it was also raining. And rain meant that the clay trail up to our start-point was switching into its secondary purpose, which is as a lubricant used whe drilling for oil. Meaning that we could be sliding, sideways and screaming over the edge, just like Louise and Thelma in the film by Ridley Scott. Because Louise got it wrong: that climactic final scene wasn’t the Grand Canyon at all, it was the Utah Canyonlands.

As you’ve already worked out, we would in the event survive both bears and bentonite.

The Landrover engine fades quickly to a wide silence, the only sound the faint waterdrips off the branches. Between the pines, we find a great emptiness. We're looking down into a wide canyon valley: a valley bottomed with rock lumps lying in various directions.

Look out for the tiny cairns, and a path with a dead branch across it is an animal trail, to be avoided. The trail steepens, and zigzags down the headwall. We scramble down a bouldery gorge to find a sandy dry streambed below.

Purple sage, but also grey thornbrush and yellow rabbitbrush and any colour really so long as it isn't green. Rock walls a quarter mile away in pinky beige, like marshmallows. A rock arch shows ahead, outlined against pale grey sky. It vanishes behind a pinkish cliff, then appears again a half-mile further along.

Native Arts

The trail slants away towards the sheer wall of the canyon. This is so as to examine two small stone structures built within a dry crevice several metres above the canyon floor. Native American somethings; for this canyon once was full of wild game to hunt. The ‘somethings’ are considered to be grain stores – they're a bit too small for anything else.

Beside the grain stores an abstract figure is painted on the rain-sheltered rock wall. It's been named as 'All American Man' because of its red, white and blue pigments. This dates back to an age when people didn't care too much about being insulting to Native American traditions. “Like last year,” says Tom the New Yorker. “Or right now.”

The second afternoon, and a high gap flanked with Egyptian temple pillars, would be a magnificent doorway into the next bend of the canyon. And, indeed, cairns lead up to a tiny rat-hole down at skirting board level. There’s more Indian paintwork along the overhang, and a new valley bend below, with a trail signpost and a couple of wooden gateposts.

“Dad, where does your GPS think we are?”

I fired up the mobile phone. It think's we're already there. Peekaboo campground.

“That's what I was thinking too…”

The campground is about as different as it could be from, say, Side Farm in the English Lake District. The facilities consist of – those two wooden gateposts. I thought I smelled a primitive 'vault' toilet but it must have just been something left behind by a bear. The supposed water-source here dried up 30 years ago. Rock walls rise on all sides, apart from where a pair of wheelmarks winds away among the scrub.

UK-type jet lage makes it easy to rise at the first light of dawn, to get walking before the sun. Stars are still bright above the tent, but somehow a few raindrops are spattering in from somewhere. Ah, from the northeast, where a big blue-black cloud is just arriving. A sunbeam creeps in from under, and some distant rock towers light up like a nuclear bomb. Every few seconds is a different lighting effect: and then a huge double rainbow stretches in darkness from a spotlit rock tower to another spotlit tower at the other edge of the view.

And then the thunder.

We stop below the Indian paintings to repack the tent and put on waterproof trousers. And then it seems like we are to pass up inside a waterfall that certainly hadn't been there the evening before. But no – a small cairn stands sideways in a crack of the rocks, and at the crack’s dark end a ladder rises onto big, bare slopes of red rock: rock with little pools and streams running over it.

The cairns lead over a rounded rise, where I think Tom's moving a bit too quick – until he mentions the lightning. Then along a steep-sided bit with some nice dry overhangs to stand under and take a photograph of the great grey spaces all set about with little pointy bits.

Snaky shapes

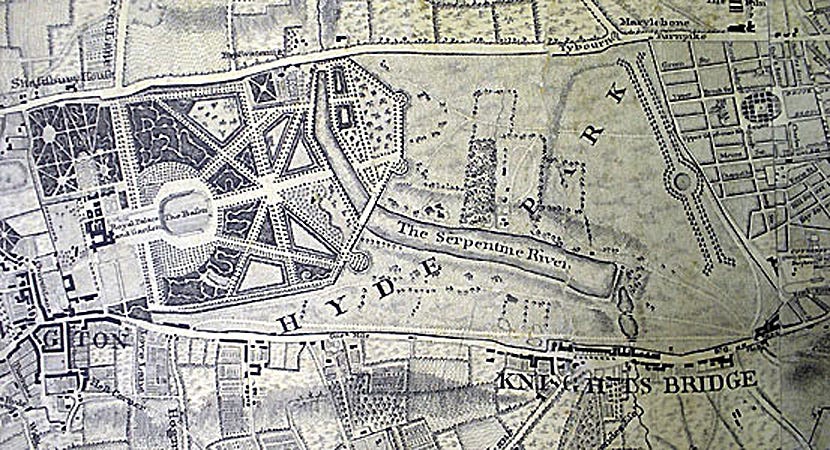

Cognitive neuroscience professor Marc G Berman, at Chicago University, has hooked people up to brain scanners and then put them in front of different sorts of scenery. He finds that landscapes with lots of curved and wavy lines stimulate the emotional centres of the mind. We like looking down into twisting canyons, and tracing the course of rivers. When he left pencils and blank pieces of paper on park benches, he found the bench-sitters looking out on curvy surfaces “wrote more about spirituality”.

These insights are not new. They were a hot topic of the mid–18th Century. Philosopher Edmund Burke wrote a treatise on the fashionable art of landscape appreciation.1 Landscapes with curves – gentle hills, flowing rivers, well fed fat cows – were worthy of being described as beautiful, because of the pleasure they provoke. And more specifically, the wavy line or ‘serpentine’ was a must-have element in the composition. “Five miles meandering with a mazy motion,” was Coleridge's dream river in ‘Kubla Khan’.

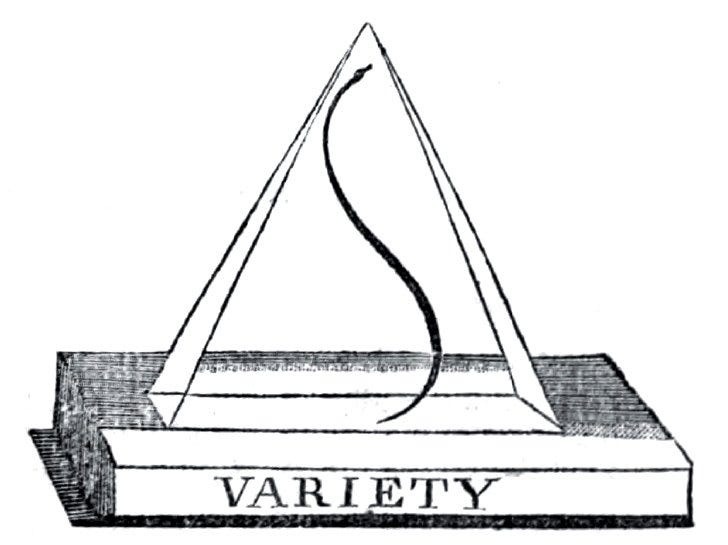

The painter and satirical engraver Hogarth (Analysis of Beauty 1753) got even more specific. The ‘line of beauty’, a curve shaped just so – whether in a chair-leg, a horse or even a corset – suggests something that’s still alive: as against the flat lines of something that’s died, the straight lines of an artificial structure.

“It is reported then that Michael Angelo vpon a time gaue this observation to the Painter Marcus de Sciena his scholler; that he should alwaies make a figure Pyramidall, Serpentlike, and multiplied by one two and three. In which precept (in mine opinion) the whole mysterie of the arte consisteth.”

To put it in its simplest terms,these curvy shapes remind these two, male, writers of an attractive young woman with no clothes on.

Walking through normal sorts of scenery, we see stuff we’re used to seeing: trees, rivers, the sloping sides of hills. All of which comes with pre-existing associations. But here in Canyonlands, the scenery is pure shape. We trace S-bends along a canyon floor, or the wiggly in-and-out shapes of a ‘bench’, a ledge formed by some slightly less erosive sandstone half way up the canyon side. Or else we’re up on the slickrock, curves and spires of bare stone.

In Squaw Canyon, as the bench we’re walking on narrows and peters out, we wonder how we're going to get up, or down, off it. Well, we aren't. A cairn stands at the opening of a narrow rock crack, and at its far end we see daylight again. Stones and tree branches are wedged in the narrowing crack below, giving foothold for the short stroll through the rockface to the other side. And leaving us wondering about the walk. Is this – it's part of the Druid Arch Trail – is it an ancient through route developed by native Americans, or Mormon scouts? Or was it put together by fanciful park rangers, drawing a Federal salary to wander the canyons and benches for the most fanciful and surprising walking effects?

For we've emerged into a pink-and-yellow striped huge hollow somewhere in the middle of the Needles. Except that not one of them actually is a needle. There are great lumpy cones like half melted ice cream. There are tall walls with cylinder outcroppings like half-seen Egyptian statues. There’s a tower like a 50ft high asparagus. The place is almost a mile wide on the map, but in reality It's the landscape so strange you can't even say what size it is – somewhere between enormous and a model two inches high made of plasticene. If you saw this place in a movie, you'd say the animators had been allowed a whole lot too far with their computer-generated landscape…

And the strangest thing about it is that, for the locals and the rangers, this is such an un-special bit of Canyonlands terrain that they haven't even given it a name. (To find it on Google Earth, just follow Squaw Canyon up the dry stream bed until it stops.)

We escape up rockfields swirled like whipped cream (pictured at the top), to a gap between a tower like a tooth and a tower like a grumpy rhinoceros. Waterscooped hollows lead down to the top of a hideous ladder. Just its two projecting handrails stick up above the rock edge, and between them I'm looking down, straight down, to near vertical rock slopes hundreds of feet below, the canyon floor even further down again.

But Tom's already down there somewhere. And then I notice a sun-shrivelled tree, lying across the vertical rockface, and the rockface is actually a gently sloping ledge, just twenty feet below me. The great forest trees spread so far below are just dried out little shrubs, and a few feet of scrambling brings us to the faraway canyon floor.

A couple of miles north along the canyon, a raven perches on a half-dead tree above Elephant Canyon campground, waiting for the crumbs of our campsite. A walker's warned us about that raven. Not only will it snatch the energy bar out of your hand between two bites; it's even worked out how to unzip your rucksack. And as we walk along the dry sand of the canyon, my wife and Tom's girlfriend are heading in from the other end, bringing in a gallon or two of water from the nearby trailhead.

Clare’s commentary: “It's like a cake that's stuck to the side of the tin, and the children have been allowed to scoop out all the middle with their fingers.” Adding, “I prefer the ones that aren't shaped like a penis.”

Edmund Burke, A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful, 1757

Ah, I've been to Canyonlands NP. My partner and I did a day walk there and it was really incredible - I've been poring over maps trying to remember which trail we did but I just can't remember now. It's about ten years ago. Thanks Ronald - I enjoyed reliving it a bit via your post. Such a stunning and unusual landscape.

What an adventure! You’re all very brave. I was in Utah a few months ago and visited the scenic Bryce Canyon. Did the tourist trail though, nice and easy. Fabulous. Nothing like it here in England! Thanks for this entertaining essay.