Theological bogs

The one landscape feature that embodies absolute evil… [1400 words 6 min

But the miry places thereof and the marishes thereof shall not be healed; they shall be given to salt.

Ezekiel 47 11

I waited patiently for the LORD, and he inclined unto me, and heard my calling.

2 He brought me also out of the horrible pit, out of the mire and clay, and set my feet upon the rock, and ordered my goings.

3 And he hath put a new song in my mouth, even a thanksgiving unto our God.

Psalm 40, Book of Common Prayer (1928)

Five days of walking from Loch Torridon bring us to a place called the Cromalt Hills. Hills they are, in terms of being up inside the grey mist and the sleet. But hills they aren't by way of being anything other than deadly flat. We wander northeast on a compass bearing, and find ourselves on the edge of a crumbly black drop.

It's only a few feet down, so down we go; and a long stride across the soggy bit in the bottom, and up the other side with just one boot blackened to the ankle. Thirty seconds later, another black drop. Down again, or find a way around? The hag cliff extends into the mist both ways, and is just as likely to lead to a dead end against another hag, and Macbeth, our man on the blasted heath, gives the best advice: “Returning were as tedious as go o'er.”1

But after half an hour of hag we drop off a peaty rim to a silver pool fading in the mist. We go left around that and the water goes left as well, and now we're heading back where we came from. So we stop and see if we can get waterproof trousers over our very sore feet without falling over in the swamp.

“Court holy-water in a dry house is better than this rain-water out o’ door.”2 Shakespeare's wild-country guide is the Fool in King Lear, who has sensible advice for long-distance walkers in the north of Scotland. It takes four hours to emerge to the dry house – it’s at a place called Altnacealgach. Court holy-water isn’t on offer, but they do have some beer.

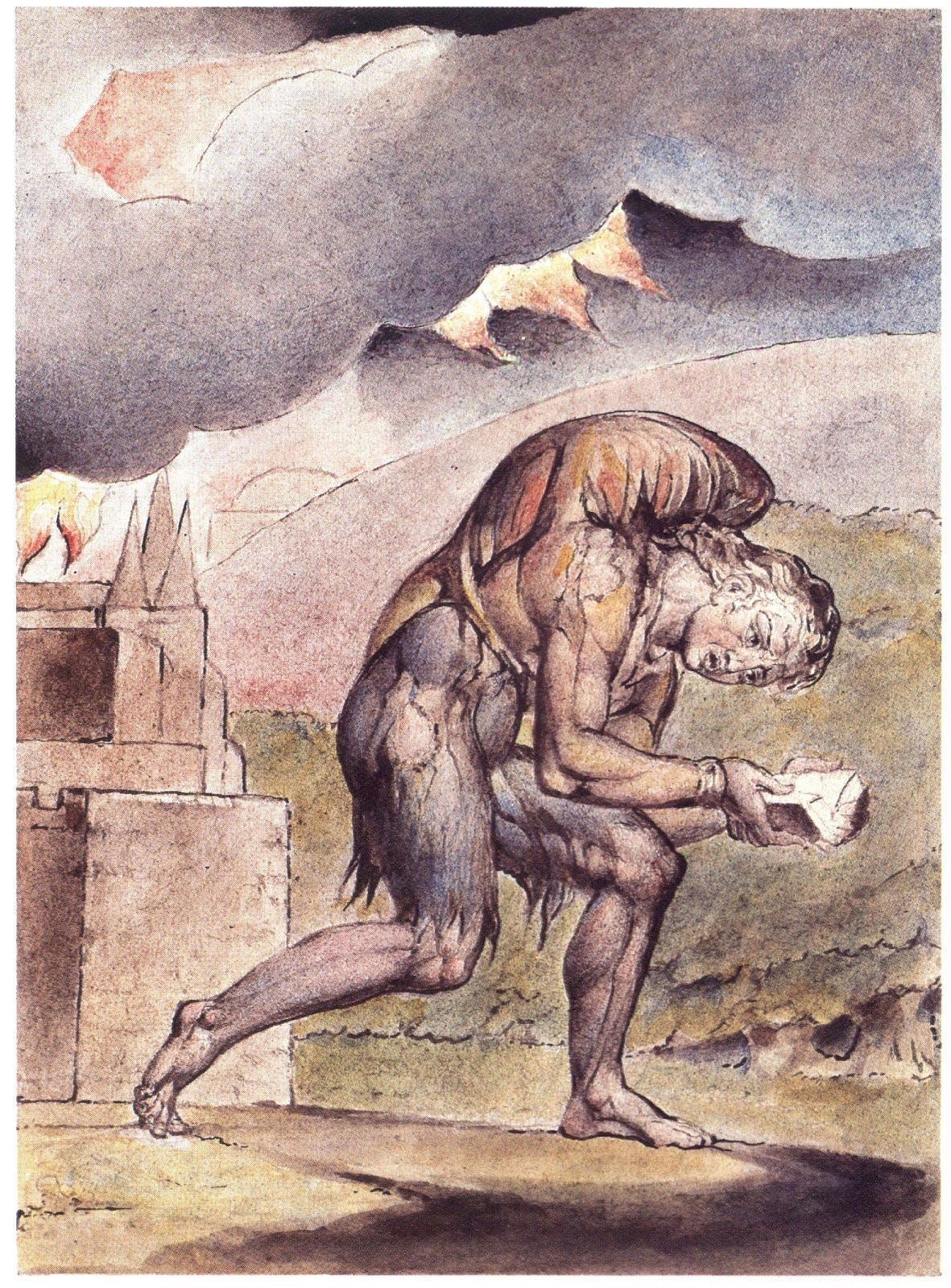

John Bunyan, author of ‘Pilgrim’s Progress’, spent three years in the Parliamentary army during the English Civil War, then lived as a travelling tinker and preacher. He knew all about long distance travel over rough roads under a heavy backpack. And his pilgrim, Christian – “a man clothed in rags standing in a certain place, with his face from his own house, a book in his hand, and a great burden upon his back...” – his guidebook is the Bible but otherwise he could be any long-distance walker along the West Highland Way. And only a mile or two into his trip, he finds himself in a sticky situation.

Now I saw in my Dream, that they drew near to a very miry Slough, that was in the midst of the plain; and they, being heedless, did both fall suddenly into the bog. The name of the slough was Despond. Here therefore they wallowed for a time, being grievously bedaubed with the dirt; and Christian, because of the Burden that was on his back, began to sink in the mire.

A boggy bit right at the beginning can be seriously discouraging. Having crossed Knockquhassan Moor on Day 1 of the Southern Upland Way I know just what poor Pilgrim felt like.

Christian’s Guidebook in its sombre black binding is thicker and heavier than the 200g of ‘Walking the Southern Upland Way’. It’s also rather less specific. At the Slough of Despond, Bunyan simply refers the walker to Isaiah XXV verses 3, 4, 8: “Strengthen ye the weak hands, and confirm the feeble knees.... And an highway shall be there, and a way, and it shall be called The way of holiness; the unclean shall not pass over it; but it shall be for those: the wayfaring men, though fools, shall not err therein.” The helper called Help does note, though, that the relevant footpath authorities have been trying to sort the place for the last 1600 years.

It wasn’t so strange, in the seventeenth century, that a principal road across the country should be so deep in mud that a traveller might sink right into it. A hundred years later, you still avoided going anywhere at all in the autumn months – four days of rain on the roads, in Pride and Prejudice, are enough to prevent even so crucial an errand as shoe-roses for the Netherton ball. Bunyan’s go-to (or don't-go-to) bog was, in worldly life, Squitch Fen near Harrowden on the southern edge of Bedford. In the following centuries it was dug out into clay pits for brickworks. These were worked out and the place is now, in a nice return of history, a wetlands reserve. A teenager is said to have enmired herself as recently as the 1940s.

Ungodly bogs

Theological bogs include the Third Circle of Dante's Inferno, where the gluttons lie in mud under pelting rain, hail and foul water, being torn about by Cerberus the dog of the Afterlife.

Grandine grossa, acqua tinta e neve

per l’aere tenebroso si riversa;

pute la terra che questo riceve.Great hail, sharp snow and water yellow-stained

Flowed like a river down the shady air;

Stank all that ground on which that rainfall fell.‘Inferno’ Canto VI line 10 (my translation)

John Bunyan’s long-distance walker escapes with the help of a helpful passer-by called Help. But Dante’s gluttons are condemned for ever. Detective writer Dorothy L Sayers was the brave choice of translator for Dante’s Penguin Classics edition of 1949. She explains that “the surrender to sin which began with mutual indulgence [the lustful, in the Second Circle] leads by an imperceptible degradation to solitary self-indulgence”. The gluttons, blinded by the mire, are unaware of their fellow-sufferers around them: this symbolising their lack of social skills in life. Instead of wallowing in soft cushions and chocolate, here they lie like pigs in actual shit.

From bog to swamp: after passing the Fourth Circle where the misers and the spendthrifts roll huge boulders at each other, Dante brings us to the River Styx. While they walked through the bog of the gluttons, now they must take to a boat to cross the stinking slime. Here those who sank into the sin of wrath, the foul-tempered and the sulky, wallow in the product of their own incontinence, wreathed in foul mist that reflects the rank emotional cloud (accidïoso fummo; in Longfellow’s translation the sluggish reek) they carried through the sweet airs of the sunlit world above.

And should we not also cite the twentieth-century reinterpretation of Dante: the sketch from Monty Python’s ‘The meaning of Life’? The glutton Mr Creosote, played by Terry Jones, receives the entire menu mixed together in a bucket with the quail eggs on top. After the ingratiating waiter, played by John Cleese, offers the final after-dinner mint – “Just one … it's only waffer thin” – Mr Creosote spectacularly explodes, swamping the elegant restaurant and the other diners with brown intestinal slime.

Today we tend to talk up the bogland and the swamp. It harbours rare plants and wildlife; it sequesters carbon; it preserves the river-valleys around it from flooding. The Sutherland Flow Country, Scotland’s second-biggest bog, has just achieved World Heritage Status.

But try to come down Wythburn, in the English Lake District, in the dark. Take a stroll along the Lyke Wake Walk in north Yorkshire with the Lyke Wake Dirge droning in your ears. Cross Rannoch Moor at the end of a wet spring season. Feel the turf trembling as you step on it; sink to your knees, or deeper; and find yourself agreeing with Ezekiel. The miry places and the marishes thereof: not nice.

Not nice at all.

Macbeth Act 3 scene iv. I am in blood stepped in so deep…

King Lear Act 3 scene ii. Court holy-water: flattery and insincere words sprinkled around at the King’s court in the same way as holy-water is used in church.

Best (and only, but I can’t imagine a better) gathering of bogs and slops literature I’ve ever come across. Repulsive yet engrossing. Great piece of work, Ronald!

Enjoyed this boggy round-up.

The movie, Labyrinth, features a rather memorable, flatulent bog - 'The Bog of Eternal Stench' (presided over by the hilarious Sir Didymus). Otherwise, I don't think I've encountered many in life or reading!