The Psychopathology of Peakbagging

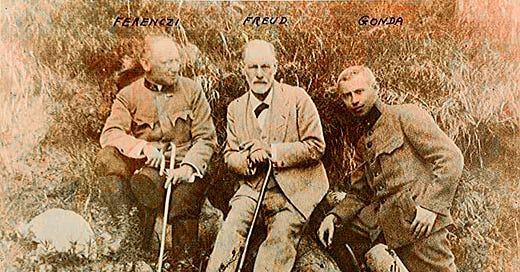

Sigmund Freud’s insights on the Outdoors [1700 words; 8 mins

And so, in my dream, I stopped to rest on a rock, somewhere low down in the High Tatras. Last night’s thunderstorm had left wisps of cloud trapped in the pine tops, like sheep’s wool caught in a fence; the clatter of the rack railway drifted up through the green air; pale granite lurked in the sky. And on the rock beside me – still in my dream – surely I recognised that trim little beard, the rounded spectacles, the jaunty Tyrolean hat.

“Herr Freud,” I greeted him in the fluent German that, alas, it is only in my dreams that I am able to deploy. “Was zum Teufel machen wir an diesem unheimlichen Ort?”1

Sigmund Freud – for indeed it was he – gestured with his cigar towards Jahnaci Stit, smiling at the obvious phallic correspondence. “Given that almost 10% of the UK's inhabitants visit your Lake District in any year, we should not be looking for an explanation of this tendency in any abnormal psychology,” he told me reassuringly. “I myself, in moments of recreation, even walked once over the Morteratsch Glacier.”

“Crevasses,” I murmured. “Deep movements, out of sight below the surface.”

He nodded, the feather of his little hat bobbing against the grim granite above us.

“Hillwalking is normal – ordinary human behaviour, insofar as any act is entitled to that claim. Its explanation should be sought in the normal abnormalities of the standard psyche, with its repressions, its sublimations, and its wealth of internal conflicts.”

He offered me a small cigar, which I accepted. Fellow males, for a few moments we fiddled about with our phallic substitutes before slotting them into our respective mouths.

“During the first two years of life, the stage of oral sexuality, the infant learns to walk – but not to climb mountains. More relevant is the following stage, of anal sexuality, or potty training. Between the age of two and three years, the sexual drives focus on the, how you say it?” Courteously, he was speaking now in his heavily accented English. “Yes, on the bum hole. Those who have failed satisfactorily to move through this stage will in later life suffer one of two possible problems.”

The granite below my own bum was warm in the afternoon; our cigars scented the sunlit air. I nodded for him to go on.

“Over indulgent toilet training leads to the anal expulsive fixation. People who were allowed to play with their poos too much turn out sloppy, unhygienic and careless.”

I had to smile at that, thinking of my companion on the Kungsleden the previous summer. “Such a one,” I put in, “may make a pleasant companion on the trail, once you get him onto the trail. But that probably isn't until 10am – and three days into the hike he goes down with Giardia due to inadequate camp hygiene.”

“Too much punishment associated with toilet training, on the other hand, will lead to the anal-retentive personality disorder: extreme tidiness, perfectionism, and over-organisation. The anally retentive will list his targets, tick them off, and aim to complete the entirety of the list. That list may be postage stamps, it may be fine wines, it may be the larger mountaintops of Scotland.”

“Not a Munro-bagger me,” I put in quickly. “Only done 172 of them, not actually ticking them off you know.”

Herr F waved his cigar expansively, conceding my point. “Munros or garden gnomes; Welsh love spoons or classic motor cars: whatever it may be that is accumulated is a symbol, unrecognised by the conscious mind, of the juicy brown poos that the unfortunate was prevented from playing with in his early years. That said, a mountain like Great Dodd or Glas Maol is appropriately rounded and soggy-brown, which a wall-mounted collector plate, a postage stamp, or Scafell Pike, is not.”

“The anal retentive,” I suggested, “is an excellent person to share a tent with. He or she knows where to find stuff in the rucksack, always has dry matches as well as a lighter in reserve. A camper who doesn't count the pegs back into their bag ends up with a flaccid tent.”

Night has fallen now; and in my dream I find ourselves in – can it be? Yes, it’s Kinbreac Bothy, in the heart of the northwest Highlands. In these long-ago days the roof-space remains uninsulated: the rain patters on the slates with a noise like the primordial heartbeat. By the light of the fire, the great psychologist tidies his beard with a small pair of scissors and stores the clippings in the special oilskin bag he carries for the purpose. He goes on to explain that, sadly for those of us seeking the ideal tent or bothy companion, not all ascenders of hills are of the anally retentive, peakbagging pattern. Most who walk in the Lake District, for example, are not ticking off the Wainwrights – they are, indeed, content to go up Great Gable or Helvellyn again and again. We must look, for further understanding, into the next development of the psyche: the phallic stage. From the age of 5 1/2 years, the child's sexuality centres on the penis, and on the turmoil of the Oedipal crisis.

“Phallic eroticism,” he explained softly, the cigar smoke rising into the shadows below the roof. “This manifests at first as ‘polymorphous perversity’: everything is sexy, from your great-uncle to your Gore-tex overtrousers. Over- or under-indulgence leads to fixation and the phallic personality, which is self-assured, vain, impulsive and narcissistic. Such a person, who fails to resolve his oedipal conflicts but carries them with him into maturity, is unable to direct his libido away from his own mother-figure – unless it is to obstruct it altogether by directing it inward onto himself. His unresolved urge to destroy the father is repressed – and hence unresolved – for fear that an understandably aggrieved father will destroy him first by robbing him of what is most precious of all, his little willy. That father, so intractable, so huge, and so emotionally inert, is well represented by Ben Nevis or the North Face of the Eiger. By symbolically ‘getting on top of’ these huge lumps of terrain, the mountain climber may overcome the Oedipal urge and attain, eventually, to a mature sexuality.”

Was that a small bothy mouse, in the shadows under the firestep? Or else, this being a dream, is it merely a small but intrusive contradiction within the exegesis. “In today’s age,” I pointed out, “we must fact the fact that some children, even some mountain climbers, aren’t actually boys.”

Freud tossed his cigar-end into the fireplace, pulled his sack towards him and started fumbling for a replacement.

“Little boys are worried that their penis may be chopped off: a little girl discovers, to her horror, that this has already happened. Penis envy accounts for some at least of the small number of female mountain practitioners. By scaling the Matterhorn, Clach Glas, or the Napes Needle, she symbolically regains her lost phallus. By ‘getting up it’ she is at the same time ‘getting it up’.”

“So is mountain climbing,” I asked slowly, “a neurotic displacement activity?” Freud is now squatting against the summit trig point – the sea sparkles in the distance, we seem to be somewhere in north Wales: can this be Cnicht?2

Freud lights up another cigar and smilingly dissents. “Not necessarily neurotic: mountaintops are, literally, ‘out there’ and in the wild. They are perceived as, and in a few cases actually are, land in its untamed savage state. In this context it is noteworthy that hill-goers value above almost anything an absence of fellow-humans on their hill. Thus a flat-topped and boggy moorland, such as the land at the back of Skiddaw in the English Lake District, will be commended not for its intrinsic attractions – except to those anally expulsive lovers of peaty mud described above, it has none – but specifically because its lack of attractions leaves it relatively unpeopled.”

And I recalled something I’d read in one of the outdoor magazines. ‘At the back o' Skiddaw,’ wrote one outdoor writer, ‘sheep outnumber people; and the walkers you meet wear smiles of quiet satisfaction.’ Had I – no, surely not – but could it be that I even wrote those words myself?

Meanwhile, the great psychologist has spread his handkerchief across the top surface of the trig point and is unwrapping some pickles and a greasy looking sausage. “Exactly so. That statement gives us a clue to what is going on here. The writer, prompted by his unconscious, is unintentionally revealing a desire for sexual congress with his wooly friends – a desire also symbolised by the wooly hats worn by the hill-goers of England. This desire is not in every case to be interpreted literally. Rather, it expresses a need to establish contact with the animal within; with the primitive turmoil of the Id and the unconscious drives that emanate from it. In the Märchen, the so-called Fairy Tales, the child hero must venture into the forest, symbolising his own unconscious mind; there he will encounter Mother-witches and Daddy-dragons, and animals both fearsome and benevolent. Integration is accomplished not by turning away from the forest, not by repression; but rather by collaborating with the friendly forest creatures, while tricking the fearsome into submission.”

Atop the trig point, sunlight bounces off the slippery surface of the sausage.

“We suspect that, alongside the symbolic adventures of dreams, and the enlightenment achieved through a course of psychoanalysis, ventures into the real-world physical ‘wild’ may not be without value in reconciling the civilised Ego with the wild urges of the Id. The scrambler along Sharp Edge, the cramponed walker along the Eiger’s summit arête, will at last attain to a ‘well-balanced’ psyche.”

“So,” I said thoughtfully. “This climbing up of mountains and climbing back down them again – ”

“Quite so,” he said with a smile. “Can, under some circumstances, be considered as being almost not neurotic at all.”3

What the devil are we doing in this uncanny spot?

Nope. No trig point on Cnicht.

Freud: ‘On Narcissm’; ‘On the Infantile Sexuality’; ‘The Psychopathology of Everyday Life’. And the rest of it, I’m afraid I just made it all up.

I recommend this be read with a good cigar.