The Mountains and the Sea

“Two Voices are there,” according to Wordsworth: the Mountains, and the Sea. Suggesting that small boat stuff is a sort of horizontal mountains. [1000 words; 5 mins

Two Voices are there; one is of the Sea,

One of the Mountains; each a mighty Voice:

In both from age to age Thou didst rejoice,

They were thy chosen Music, Liberty!

Okay, so Wordsworth’s sonnet [full text here] is actually about politics. The first Voice of Liberty, sounding in the falling waterfalls of Switzerland, has just been shouted down by Napoleon and his armies. The second Voice, the wave-crash of the Channel, will (with luck) maintain the old aristocratic order under our nice, civilised King.1

But if stuff in small boats really is a sort of horizontal mountaineering, just with even damper underclothing – can the ocean goers tell us something about what we’re up to when we’re going up a hill?

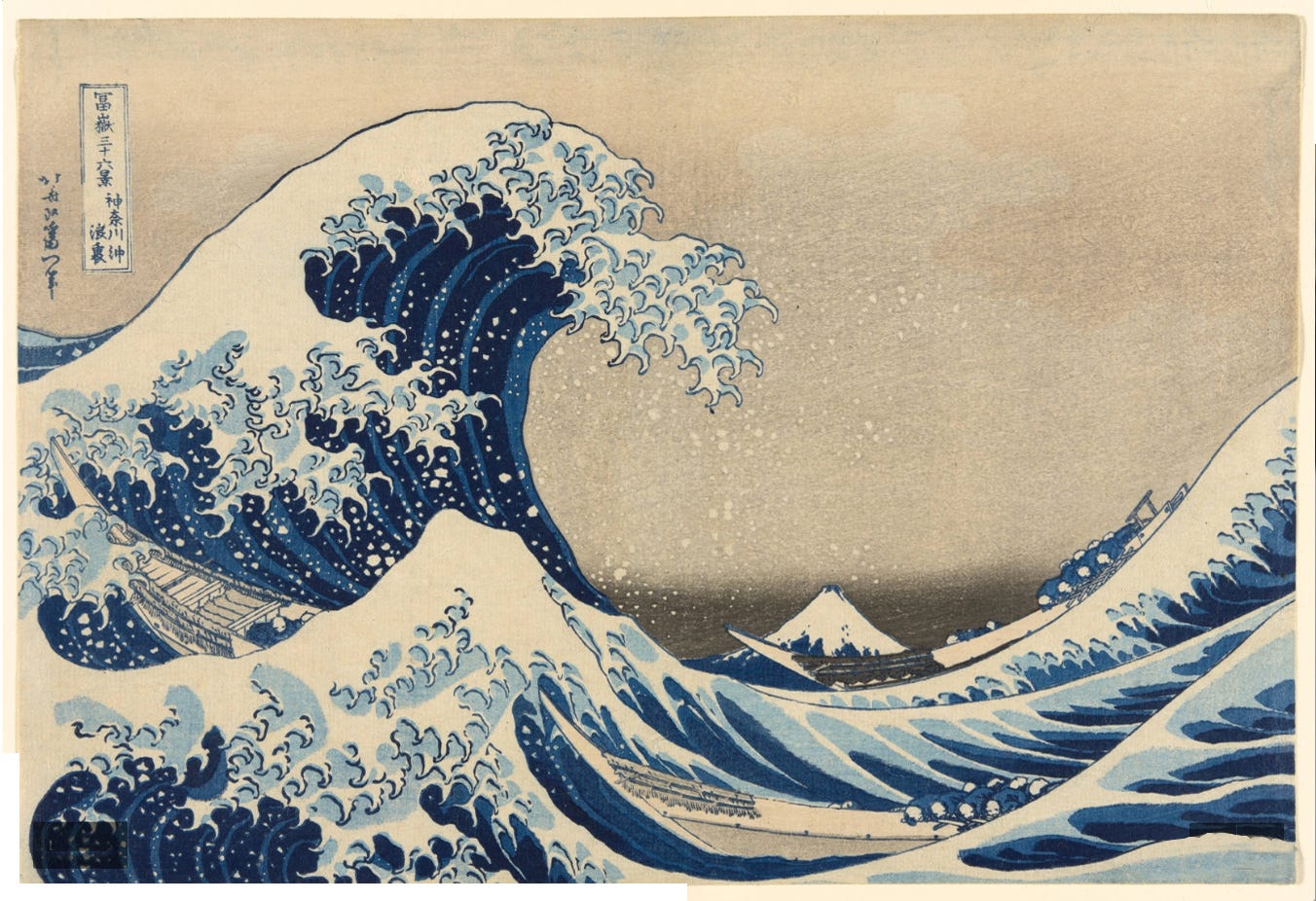

Mount Fuji, and some small boats: ‘The Great Wave’ woodblock print by Hokusai (1831) is the first of his ‘Thirty Six Views of Mount Fuji’

The mountains rise huge and solid through the stormclouds of emotion that make up the English poetry of the early 1800s. Coleridge, the Wordsworths William and Dorothy, Byron, Keats: mountain climbers, every one. But the one great mountain poem of the Romantics is written by Percy Bysshe Shelley – whose sport was in small boats.

The mountain is Mont Blanc.

In the calm darkness of the moonless nights,

In the lone glare of day, the snows descend

Upon that Mountain; none beholds them there,

Nor when the flakes burn in the sinking sun,

Or the star-beams dart through them.

Shelley wrote it (my account of the poem on UKhillwalking.com here) but never went up it – or any other significant hill, so far as I can see. A long distance walker, yes, with his girlfriend Mary and her half-sister Claire Clairmont, across France to the bottom of the mountain. And adventure sports generally: "I have been familiar from boyhood with mountains and lakes, and the sea and the solitude of forests. Danger which sports upon the brink of precipices has been my playmate."2 But when it came to serious, life-threatening recreation, Shelley’s thing was small boats in storms. There was the overnight crossing of the Channel in 1814. A dodgy day-trip with Byron on the Lake of Geneva. And his final, life-ending outing in the Bay of Naples, his 7m two-master Don Juan, named after a poem by Byron and carrying far too much sail for her size.

Shelley’s cremation on the beach, watched by Leigh Hunt and Byron (Louis Edward Fournier 1889 / National Museums Liverpool )

And turning things right around, the great Romantic poem of the sea, the ‘Rime of the Ancient Mariner’ is by the fellwalker Coleridge. Whose only voyage had been the Chepstow ferry across the River Severn: his ocean-going adventures all the more real for being entirely in the realm of the imagination.

Fun in small boats: Wood engraving (1875) by Gustave Doré for ‘Rime of the Ancient Mariner’

But there’ve been a couple of our mountaineers who have heard the raucous calling of both Wordsworth’s mighty Voices: the hilltops and also the ocean.

Bill Tillman’s introduction to mountaineering was being roped up by Eric Shipton for the first ascent of Mount Kenya. He went on to lead the 1936 ascent of Nanda Devi, at 7816m the highest mountain then climbed: “I believe we so far forgot ourselves as to shake hands on it.” He also led the 1938 Everest attempt, where he reached 8300m without bottled oxygen. Then suddenly, at the age of 57, he transfers to the Bristol Channel pilot cutter Mischief, for expeditions to the Antarctic. “Hands wanted for long voyage in small boat. No pay, no prospects, not much pleasure.” And sailed on into his 80th year, when the converted steel tugboat En Avant sank somewhere among the ice floes on the way to the Falkland Islands.

Cover of JRL Anderson’s biography. But Bill Tillman himself wrote 15 books about his own life (7 mountaineering, 8 sailing)

For an elderly mountain person who’s still after some life-threatening form of fun, boating could be just the thing. When it comes to mountains, around the age of 57 we do start being a little bit worse at it with every year. While in boats, the Ancient Mariner just goes on getting craftier.

But for enjoying both forms of dangerous fun at once – switching between the loose black basalt of the Devil’s Kitchen and a leaky rowing boat on its way to the Isle of Skye: that has to be the great Welsh climber J Menlove Edwards. When it came to the classic rock routes in Snowdonia, Menlove didn’t just climb it, he wrote the guidebook as well. Meanwhile his horizontal projects included swimming the Linn of Dee in spate conditions, and a solo crossing to the Isle of Man in a collapsible canoe.

Devil’s Kitchen, Cwm Idwal. Damp, loose and unreliable, and Menlove himself was much the same

If rockclimbing is a form of art – which it is – then Menlove is the tormented genius, rockclimbing’s Van Gogh. And like Van Gogh, he died by suicide. No, I don’t mean by falling off a high rockface or drowning in the Atlantic – Menlove killed himself at ground level, with poison.3

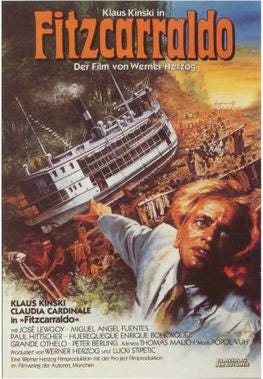

Just one man has managed to combine boats with mountain-climbing in a simultaneous endeavour. Film-maker Werner Herzog, in Fitzcarraldo (1982), drags a paddle steamer over what’s described as a mountain in the Amazon jungle. Okay, it’s not a mountain as such, a mere matter of a watershed between two river systems. But to shoot the film, Herzog did indeed get hold of a paddle steamer and have it dragged across a watershed in the Amazon jungle. “If I abandon this project I would be a man without dreams and I don't want to live like that: I live my life or I end my life with this project.”

But it’s Herzog’s ‘Aguirre Wrath of God’ (1972) that documents the ultimate mountaineering expedition – apart from the minor matter of being in a boat, and downhill all the way. Well, they’re supposedly after the non-existent El Dorado, though it’s pretty clear Aguirre himself doesn’t believe in that one, just using it to encourage the others. The film was going to end with them arriving at the ocean. But that seemed too much like some sort of success or at least an outcome. So instead, we fade out on the raft circling, becalmed, in the middle of the wide river, everybody dead except Aguirre himself.

So what is the point of any life-changing or life-ending journey, whether it’s down a river or up a hill? This isn’t something that’s easily explained in words – perhaps because there is no explanation.

But for an account in pictures and emotions – you can’t do better than the hour and 34 minutes of ‘Aguirre, Wrath of God’. The boat trip is pointless, dangerous, and extremely uncomfortable. Aguirre himself makes mountaineer Don Whillans seem like a sweetie and Menlove Edwards a well balanced, sensible fellow. Nothing could be more nasty, brutish and futile than Aguirre’s raft trip down the river. And yet, somehow, it makes sense.

Well, we’re mountain climbers. We knew that anyway.

And yes, this poem was memorably mangled by JK Stephen to describe Wordsworth’s own poetry: “Two voices are there: one is of the Deep, And one is of an old half-witted Sheep: Both thine, O Wordsworth!” Poem here .

Preface to ‘Laon and Cythna’, also known as ‘The Revolt of Islam’, one of Shelley’s long political poems. Haven’t read it, sorry.