The mistakes of others

It’s good to learn from your mistakes. It’s even better to learn from other people’s ones. (Warren Buffet) [1500 words, 6 mins

Where I went ski-ing once, there was a sad story from the week before about two English people. The first was a solo ski-er who’d lifted up the red warning tape at the edge of the piste and ski-ed the wild country beyond: ski-ed, indeed, over a cliff. That story, I felt, had nothing to tell me. The guy had taken a risk for the sake of the fine powder snow on the other side. Such a risk is justified so long as you get away with it, and criminally irresponsible only when you don’t.

“ It is much easier, as well as far more enjoyable, to identify and label the mistakes of others than to recognise our own.”

Thinking, Fast and Slow (Introduction) Daniel Kahneman

But the interesting bit came a couple of hours later, when the second English ski-er saw the ski tracks running underneath the warning tape, went ‘well someone else has gone down there so it must be okay’, and proceeded to ski over the very same cliff. At the time I thought the person’s Englishness was relevant – us Brits being sheep-like and so conventional. But in fact, it could happen to any nationality, even an aggressively self-determined citizen of America. Whatever the books say, or the statistics, we’re influenced most by other people in our immediate surroundings. And again and again we see that one person wandering wrong will be followed by several others. So inconvenient for the Lochaber Mountain Rescue, they way they never get to winch just one party out of Five Finger Gully, but also the second lot who followed the first ones down.

Ah, those case studies from the British Mountaineering Council. How intriguing the anecdotes, and what quiet satisfaction we get from reading them through and working out several reasons why that particular accident would never have happened to us, of course it wouldn’t.

Such assessments come so easily, when we’re sitting at home, in the warm, with a bloodstream that’s got some nice glucose in it and is flowing reasonably freely by way of water supply. Possibly we should be simulating, instead, the thinking conditions of a more plausible mountainside. This could be achieved by assessing the accidents after drinking a good half bottle of red wine, or some other alcohol-based self-poisoning.

Here’s an example of authentic mountain thought. It’s 2008, and for several days Conrad Anker, Jimmy Chin and Renan Ozturk have been hauling 200lb of gear up steep snow-ice.

Renan: I think it’s two in the morning. We went for the ghetto bivvy on the shoulder instead of setting up the ledge [the portaledge]. It’s a lot easier.

Jimmy: Tell us the reason, the real reason why we didn’t set up anything.

Renan (chuckles) Cos we’re worked a little bit, maybe!

My post about this excellent mountain movie was here.

Many people are overconfident, prone to place too much faith in their intuitions. They apparently find cognitive effort [System 2 thinking] at least mildly unpleasant and avoid it as much as possible.

Daniel Kahneman, who died last year, was so good they went: seeing as there isn’t a Nobel Prize for behavioral psychology let’s give him the one for Economics. Another earlier post, here, described his experiments into the well known mountain mindset whereby an experience that is utterly horrible at the time, two weeks later becomes a fun adventure that we can’t wait to do it all over again.

But in the earlier chapters of his book ‘Thinking Fast and Slow’ (2011) Kahneman worked out that we humans have two separate ways of deciding about things: intuition, and reasoning. Or what he called System One Thinking and System Two Thinking. System One, intuition, is “that stranger in you, which may be in control of much of what you do, although you rarely have a glimpse of it.” System One’s decisions are the ones you’re hardly aware of taking. When your rope-partner falls off an Alpine ridge, the leap for a belay you didn’t know you’d noticed. That sudden moment when you realise this isn’t fun and you’ve already decided to turn back. “Good intuitive judgments come to mind with the same immediacy as [a two-year-old who looks at a dog and says] ‘Doggie!’ ” Unfortunately…

Unfortunately, so do bad ones. System One uses quick, simple reasoning methods such as ‘Associative Memory’. Miguel has really nice gear: THEREFORE he’s a capable and trustworthy mountain guide, let’s hire him. Someone else’s footprints are down that snowslope so YES, it’s FINE in terms of an avalanche. We’re tired and it’s an extra two miles around by the canyon floor so NO there’s NO risk of lightning during this particular bit of rainfall.

A remarkable aspect of your mental life is that you are rarely stumped…. You have intuitive feelings and opinions about almost everything that comes your way…. you feel that an enterprise is bound to succeed without analyzing it…

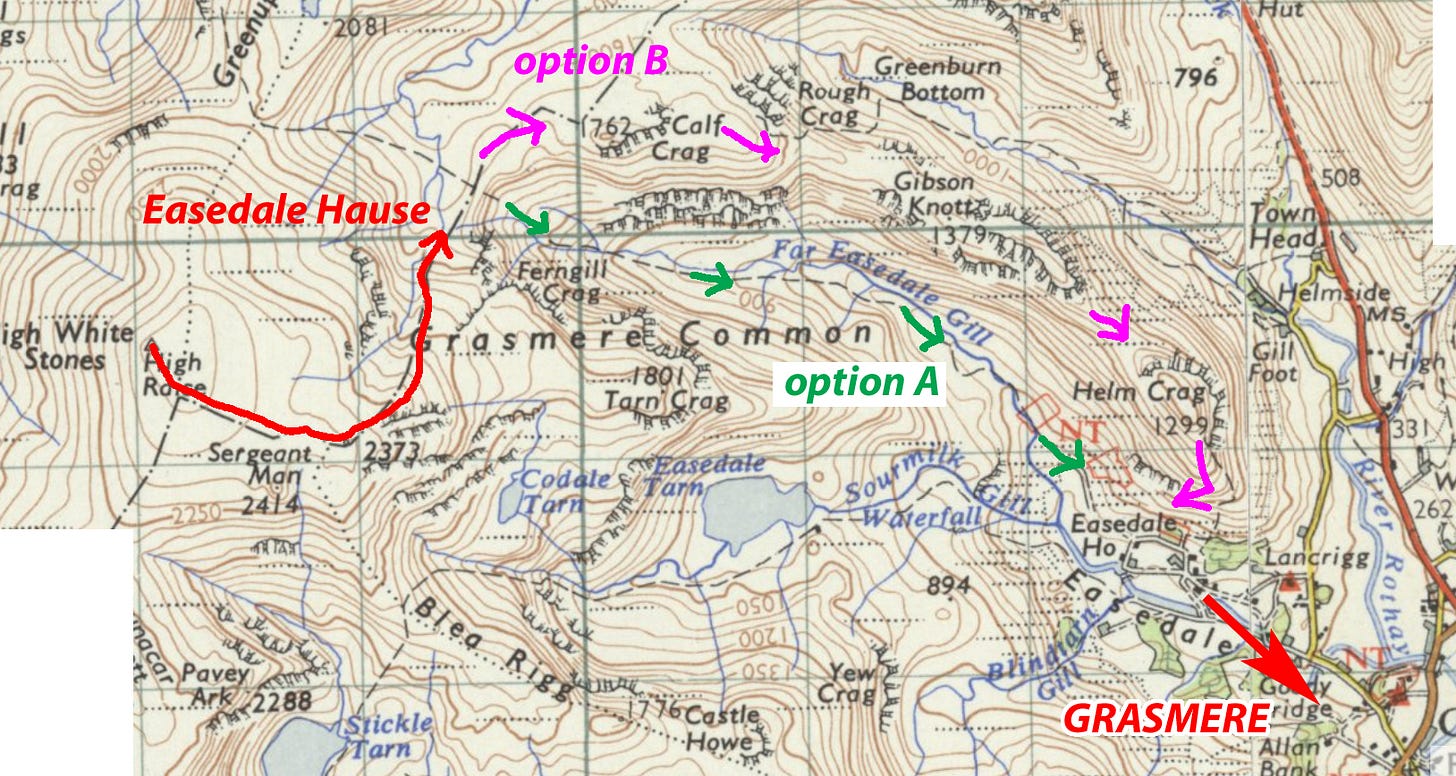

Far Easedale uncertainty

Let’s apply this to a chap above the top end of Far Easedale who wrote up his slightly dodgy walk in Lakeland Walker magazine. He’s come down to the pass already tired out, and with only an hour left of daylight; he’s used up all his food and water. He has two choices:

Option A The rather steep descent to the head of Far Easedale and a wide, sheltered path down the valley.

Option B Staying high around the valley rim, with a descent and re-climb to Helm Crag, and then a steep and stony descent to the Grasmere road.

Even without getting the map out, this seems like an easy one. (When you’re tired and in a hurry, not getting out the map saves not only time but mental effort as well…) Here’s what our walker would have seen, just supposing they did take out their map, and also supposing they were walking back in the 1960s with the old one-inch map that’s now come out of copyright.

Option B is longer, and has extra uphill as well. Off Helm Crag it has a similar steep descent section to Opetion A, but this time with a few crags to fall over, and timed so it’ll already be after dark when you get there. Obviously, Option A is the one to go for.

The Lakeland Walker walker chose Option B.

This appears as a typical System One decision, choosing the short term convenience of avoiding the steep descent into Eskdale, despite long term grief. Another motive may be that it takes less thinking-about to stick with what had been the original plan for the day.

Profesor Kahnemann tied this sort of decision-making in with glucose in the blood. System Two, the one that thinks things through, is lazy and easily tired. Experimentally, he found that a hit of glucose leads to more thought-through, System 2–type decisions. And they tell us that a Mars Bar is bad for your health…

The LW contributor did indeed suffer a highly unpleasant descent from Helm Crag. I didn’t record his name, but LW readers should be grateful for the frank way he passed on his daywalk (and a bit of the night) story. Dehydration, of course, is another likely factor. He’d just passed a lively stream. A fixed idea that ‘drinking from mountain streams is BAD’, even when dehydration is about to lead to potentially dangerous lapses of judgment: this is typical System One thinking.1

For some of our most important beliefs we have no evidence at all, except that people we love and trust hold these beliefs. Considering how little we know, the confidence we have in our beliefs is preposterous—and it is also essential.

Perhaps this is telling us what we already know. Thinking is tough – sometimes, it’s just too tough. When tired and dehydrated, it’s easiest to stick to the existing plan rather than thinking up something new. I’ve climbed four of the 8000-ers while remaining still alive, clearly I have special skills that will assure success on K2, Broad Peak and Annapurna too. When the fingers are a bit chilly and the zip jams, the straightforward thing is to swear at it and give it a good hard tug. Same tactics may even work on walking companions….

All pretty obvious, perhaps. But still it’s useful to have it confirmed for us by a recently-dead Nobel Prize winner.

It’s a while ago, and I don’t have the walker’s name: if you recognise yourself here, please consider yourself sincerely thanked for your very useful account.

I recently managed to end up on a small but wickedly steep bit of gorge on what was supposed to be a simple rural ballade, and it was amazing how much my judgement was influenced by seeing little trails leading along the side, plus my intended destination appearing so close on the non-topo map, even though the thinking-through part of me was shaking its head. The stakes weren't too high but I did get into the trickiest slide I ever remember having to pull myself out of via trees and then finally go back the way I had come. The worst part is, I had started down the real path that went around the gorge a while before, but I was (shamefully) following a google maps trajectory which insisted on the other way. I didn't allow IT to lead me off a cliff (which it tried to do), but once I was over there and looking at the trails, I thought I could figure it out. Lessons learned.

It was really incredible how disorienting and inhibiting such a small patch of steep topography (totally invisible on non-topo maps and satellite images, just looks like trees in the fields, not even labeled as a stream) can be. I'm not that experienced with topo maps or route planning, but it would be interesting to learn.

I'm no mountaineer but Ive definitely been in trouble in the Lake District because everyone in a group is assumes someone knows what they are doing... Oops, we're lost/almost fell off Sharp Edge. On the other hand, did navigate the Peloponnesian bus system once by deciding to follow the people who looked most competent ... and it worked!