The Big Brecon Ridge

Not jaggy, but flat. Not volcanic, but made of the Old Red Sandstone. Even so, this could be Britain’s biggest cliff. [1400 words 6 mins

Snowdonia is jaggy and volcanic. The Brecon Beacons, or Bannau Brycheiniog, are flat-lying sandstone. Snowdonia is covered in stones and heather, chewed at by wild goats. Brecon is gently grassy, with ponies. Snowdonia is one of the UK's very best places for mountain walking. Brecon is – one of the UK's very best places for mountain walking.

The great north-facing escarpment runs for 70km across the southern part of Wales. It's named as four separate ranges: the Black Mountains (with an s on the end), the Brecon Beacons, the Fforest Fawr, and the Black Mountain (without an s). But basically it's all one ridge.

And at its very highest point, at over 2900ft, the sandstone has ripple marks left on the sandy floor of a great freshwater lake.

The Walrus and the Carpenter

Were walking close at hand;

They wept like anything to see

Such quantities of sand:

‘If this were only cleared away,’

They said, ‘it would be grand!’Lewis Carrol, ‘The Walrus and the Carpenter’ from Alice Through the Looking-Glass

The Old Red Sandstone

So how come Pen y Fan’s summit was once so deep underwater? And where did all that sand come from in the first place?

Around 400 million years ago, a scrap of continent that we’d later be calling Scotland crashed into what would one day be England-and-Wales; throwing up a great, crumpled mountain range wehre they met. A range that’s still there, the last ancient remains of it, as what’s now the Scottish Highlands.

No sooner were the mountains up than the rain started to crumble them down and carry them away. Stones and sand spread out of the mountains, carried down stony wadis in terrifying flash floods.

The resulting sandy rubble spread outward to north and south. The mountains were big ones – at least Alpine, probably Himalayan in size – and the sandy rubble spread a long way. Spread so far that the first geologists considered the resulting Old Red Sandstone as one of the Universal Formations, covering the whole world.

But no. A lot of places, but not everywhere. Where it’s not been buried by later sediments, or carried away by erosion, the sandstone extends north of the mountains to the Orkney Islands, and across the more recent Atlantic Ocean into Greenland and the Catskill Mountains of New York state; southwards, it reaches as far as Exmoor. Within the UK, it forms its most notable hill scenery along the Brecon Beacons ranges.

Brecon Beacons

Head southwards from the edge, and you're heading upwards in time into younger rocks. At the back of the Brecon Beacons you move downhill, but upwards geologically into the Carboniferous-age Mountain Limestone. And the next younger layer southwards is the Coal Measures, giving the coalfields of the Welsh Valleys.

Northwards, though, there's the sudden sharp drop, through the layers of the red sandstone, to some softer sea-floor mudstones below. Softer rock lying below the up-ward tilting beds of sandstone is a standard set-up for a steeply defined scarp.

The path along the right hand rim of Craig y Fan Ddu is wide, and well trampled. Sleeping in the car in a high car park means that for the time being I've got it to myself. It has the steep drops to the right, and bits of sandstone crag at the rim. And among the flat-lying rock bands, there's a band of slantwise strata, like the middle stroke of the letter Z. This is cross-bedding, and it shows a sandbank in a stream or river, building up downstream.

Morning mist has been piling up above the River Usk, and at about 8am it starts flowing over the ridgeline ahead of me, like a fuzzy sort of glacier filmed in time lapse. The path crosses a thin stream running over bare rock slabs. Rippled rocks are in the stream bed, but those ripples are not recent: they were caused by that previous stream or river of the Devonian period, 350 million years ago...

By the time I reach the main north-facing escarpment above Brecon town, the mist has risen into the morning sun and snagged onto the clifftop. On the right, there's nothing to see but cloud. Which leaves me looking leftwards, at a scrap of cliff.

The red colour of the rock is ordinary iron oxide: the pigment used by stone age cave painters and still found in paint products of today.

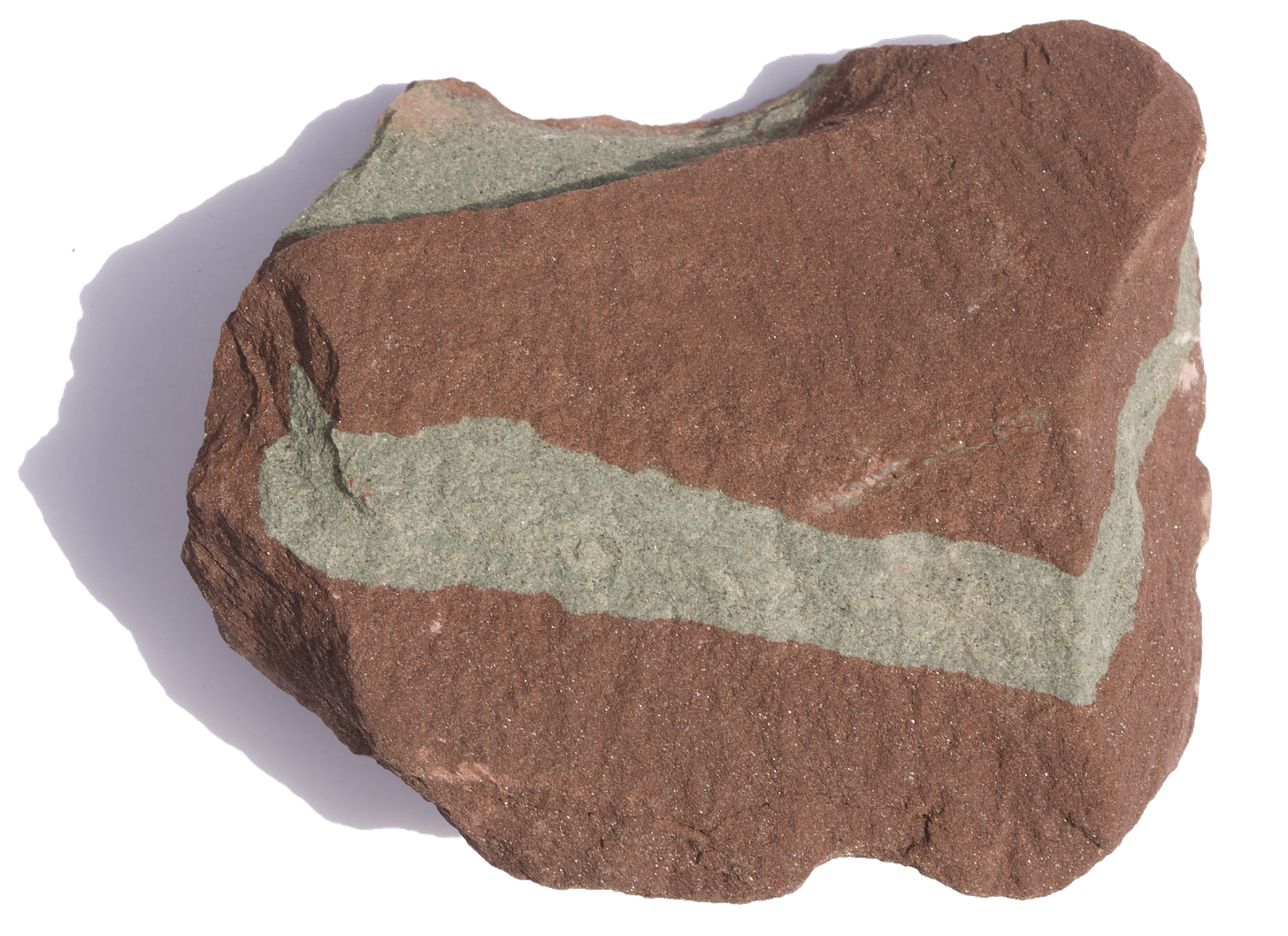

But here and there, the reddish brown of the little cliff is discoloured to a nasty grey-green. It's the colour you see on some bacon that's gone a couple of months beyond its sell-by date. When the bacon goes green, it's been invaded by all sorts of interesting lifeforms like Salmonella and E coli. And the same is true of the sandstone. On the whole, fossils aren't found in the red desert. But these off-colour bands and specks in the rock suggest the oxygen-absorbent lake floor rotting of plant life (plus insects, and the occasional four-legged fish) all bravely colonising the empty land of the Devonian.1

Even the bright-red colour of the rocks themselves is a sign of life: rusty red in the rich oxygen atmosphere built by great forests of pine and horsetail, currently greening over the parts of the continent not covered with sandy desert or stagnant shallow lakes.

Fan y Bîg (the ‘to bach’ or little roof accent ^ turns it from Big to Beeeeeg…) marks the corner of everything. It’s the prow of a big stone ship, driving forward into the mist. On the side of it, a slab of slightly harder sandstone sticks out like a tiny pirate gangplank – the 'Diving Board', a photo posing spot in front of the great northern curve of Pen y Fan. Except today it's a posing spot in front of a whole lot of blank white mist.

And it's a diving board for the Old Red itself. Northwards, it leaps upwards into the air: eroded away and invisible.

Approaching Pen y Fan, the heavily used path is built up on cobbled stonework in between slabby steps of sandstone bedrock. The uniform, narrow beds indicate a lake or sea. Each inch-thin layer could be one winter’s drop off from a single big river.

And here, at the highest point south of Snowdonia, we can see the floor of an ancient lake. All across the flat summit plateau, trampled bare by feet, the exposed rocks show lake-bottom ripples. The ripple marks are most obvious in low sunlight; they match the ones you'll see on any beach when the tide goes out.

Now, in the middle of the day, the sun is burning away the mist. On the high ridgeline west of Pen y Fan I’m suddenly in bright sunlight, on a path that’s red-coloured rather than dingy brown, between two slopes of brilliant green, all of it below a baby-blue sky. Lumps of fluffy white cloud are blocking the ridgeline behind and filling the hollows on either side. “Lucky its in cloud,” says a family Dad just up from the roadside carpark: “We can't see how far it is down.”

By the time I get to Corn Du the damp air mass has risen above the hilltops, forming a damp grey lid and dulling off the day. I leave the crowds behind again, down one of the long northward ridges: then down the steeper side on a staircase of red stone steps.

Back then during the Devonian, the four-finned Tetrapods were just crawling out of the ocean to experiment with the life of a fish out of water. Life is hard to find in deserts, especially when those deserts happened 400 million years ago. But as I head up the plantation track towards my high car park, in the decayed greenish rock bands I spot fossilised wormholes left by denizens of the sludgy lakes and stagnant river channels. Worm, shrimp, or possibly an underwater bug called a water scorpion: it’s not too hard, at the end of a long day along the Brecon Beacons, to sympathise with the ancestor crawling through the sludges of so long ago.

Normal atmosphere oxidises any iron-rich rock to rusty red. Where lake beds became stagnant and anaerobic, or oxygen-deprived, the iron is ‘reduced’ to the grey-green ferrous form. Such stagnation can often be caused by decaying organic matter snatching back oxygen atoms as it rots.

fascinating stuff. Enjoyed it, thanks Ronald.

2900feet I think, not 2900m. Pen y Fan is 886m