Suffering and fun

We should minimise our own future pain. But, as mountaineers and long distance walkers, we don't. Behavioral psychology could have some answers here. [1700 words, 8 min

Common sense suggests that we should act to minimise our own future suffering. Mountaineers and long-distance walkers seem, however, to take the opposite strategy. We sign up, not just voluntarily but enthusiastically, for projects involving blisters, frostbite and death.

So what’s going on? An Israeli-American behavioral psychologist may help to solve two of the fundamental problems of outdoor sport: the ‘That’s Neat’ moment, and the issue of Type Two Fun.

Daniel Kahneman, who died on 26 March this year, was so good they went: seeing as there isn’t a Nobel Prize for behavioral psychology, let’s give him the one for Economics.

The reason they gave him the Economics prize was that he showed that lots Economics was wrong. Economists assume that economic units, or what we would call ‘us people’, act from rational self-interest. If something we like gets cheaper, then we buy more of it. Daniel Kahneman showed, instead, that human decisions are subject to bias and irrationality. But that our bias and irrationality are often, themselves, quite predictable. And he provided various clever experiments to back it all up.

Back cover of Daniel Kahneman’s book about mountaineering (and everything else as well) – ‘Thinking, Fast and Slow’

Kahneman worked out that we humans have two separate ways of thinking about things: intuition, and reasoning. He called them, System 1 and System 2. System 1, intuition, is “that stranger in you, which may be in control of much of what you do, although you rearely have a glimpse of it”. System One’s decisions are the ones you’re hardly aware of taking. The leap for a belay you didn’t know you’d noticed when your rope-partner falls off an Alpine ridge. The sudden moment when you realise this isn’t fun and you’ve already decided to turn back. “Good intuitive judgments come to mind with the same immediacy as [a two-year-old who looks at a dog and says] ‘Doggie!’” Unfortunately…

Unfortunately, so do bad ones. System One uses quick, simple reasoning methods such as ‘Associative Memory’. Miguel has a nice smile and really nice gear: THEREFORE he’s a capable and trustworthy mountain guide. Let’s hire him.

System One offers instant decision-making without the need for conscious thought. St Paul on the road to Damascus (Brighton Oratory). Though this could also be a scene late on in an LDWA hundred-miler.

The ‘That’s Neat’ moment

A note in the hillrunners’ magazine said that there was going to be a race across Wales. All the way across Wales. From the north coast, over Snowdonia, then over Plynlimon, and down to Carreg Cennen Castle at the end of the Brecon Beacons. It was going to take five days, and there’d be a big tent to sleep in every night, and the Parachute Regiment was going to carry the luggage. But, oh look, it’s limited to 30 pairs of runners. Obviously, me and my pal Glyn need to sign up for this one right away…

Many of our most consequential decisions are the ones we make most quickly. St Paul on the road to Damascus, instantaneously deciding to be a Christian – but the same ‘sudden light from heaven’ flashes down on any mountaineer you can mention who’s just seen a picture of the Mittelegi Ridge on the Eiger.

A great day out (well, five of them). And they even gave me this paperweight!

The instant intuitions of System One don’t consciously explain themselves. My unreasoned ‘reasoning’ on the Welsh Dragon’s Back Race (expressed not as conscious thoughts, but in feelings and pictures) may have included: “I’m feeling pretty fit just now”; “I had fun on the last fifty-miler and five times as long has to be five times as much fun”; “very cheap!” (£10 for the inaugural Dragon’s Back race, it’s £1799 for this year’s one) and “Parachute Regiment carries the bags!” Clearly, there are even more significant considerations that could have been considered. In the event, it was unpleasant in several interestingly different ways. We came last, Glyn and me.1 But due to dropouts, that still put us in the first half of the field – 13th out of 27 starters – making for a useful anecdote. Well, it’s not bragging to say you came last. (Even though it is, really.)

“That’s Neat” syndrome takes its name from Bill Bryson, who happened to notice a thing called the Appalachian Trail running across the bottom of his garden. “That’s neat! Let’s do it!” committed him to three months of most entertaining (to his readers) misery, described in ‘A Walk in the Woods’.

Trees, please! Hiking in the Appalachians. This goes on for a tempting 2190 miles.

Type Two Fun

Jimmie Chin, climbing Mount Meru in the Garhwal Himalaya, didn’t have a terribly nice time. Less than a quarter of the way up, the storm closed in. The three of them spent five days dangling from the rockface in a nylon bag (or ‘Portaledge’) with avalanches pouring down on either side, in damp sleeping bags and –20° temperatures and that’s probably Farenheit at that (nearer to minus 30 in Centigrade), before trying to continue up the climb even though they didn’t have any food or fuel left. Thanks to a combination of fungus and frostbite his feet had started to decompose: when they got down again Jimmie was in a wheelchair. One thing for sure: Jimmie wasn’t going back to Meru.

Three years later, Jimmie was back on Meru. “You know, they say the best alpinists are the ones with the worst memory.”

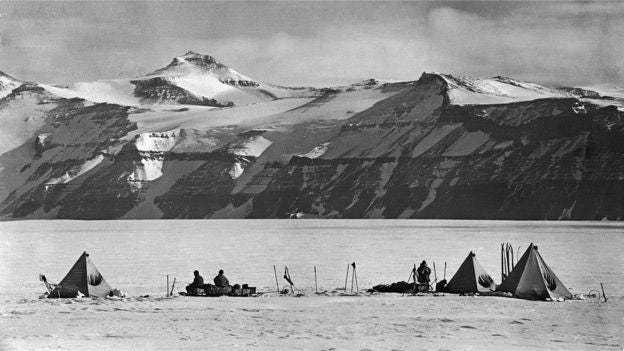

Hauling sledges in the Antarctic: not fun, and often fatal (Captain Robert Scott’s camp, from ‘The Worst Journey in the World’)

But it doesn’t have to be on any big mountain. The Long Distance Walkers Association organises a hundred-mile walk over the two days of the May bank holiday. A different place every year, but always off road, and with a minimum of 3500m of ascent. It’s not fun. It really isn’t. Not just because of the blisters, sleeplessness, cramps in the legs, falling over in the dark and stress fractures: during the second night out, the hallucinations start kicking in. On the one in the White Peak, at the 80-mile mark, I told myself: Do not forget this. This is not fun. This is unpleasant. Do not enter this event again. And I didn’t forget it. Not for quite a long time. It was two full years before I next entered the LDWA Hundred…

Exmoor Hundred, 30 miles in and first evening approaching

And thus we expose ourselves to the paradox of ‘Type Two Fun’. Type Two is the sort of fun that isn’t actually enjoyable – think sledge-hauling in the Antarctic, think the Appalachian Trail, think the LDWA’s Hundred-miler – but that masquerades as having been enjoyable when looked back at from a safe time interval afterwards.

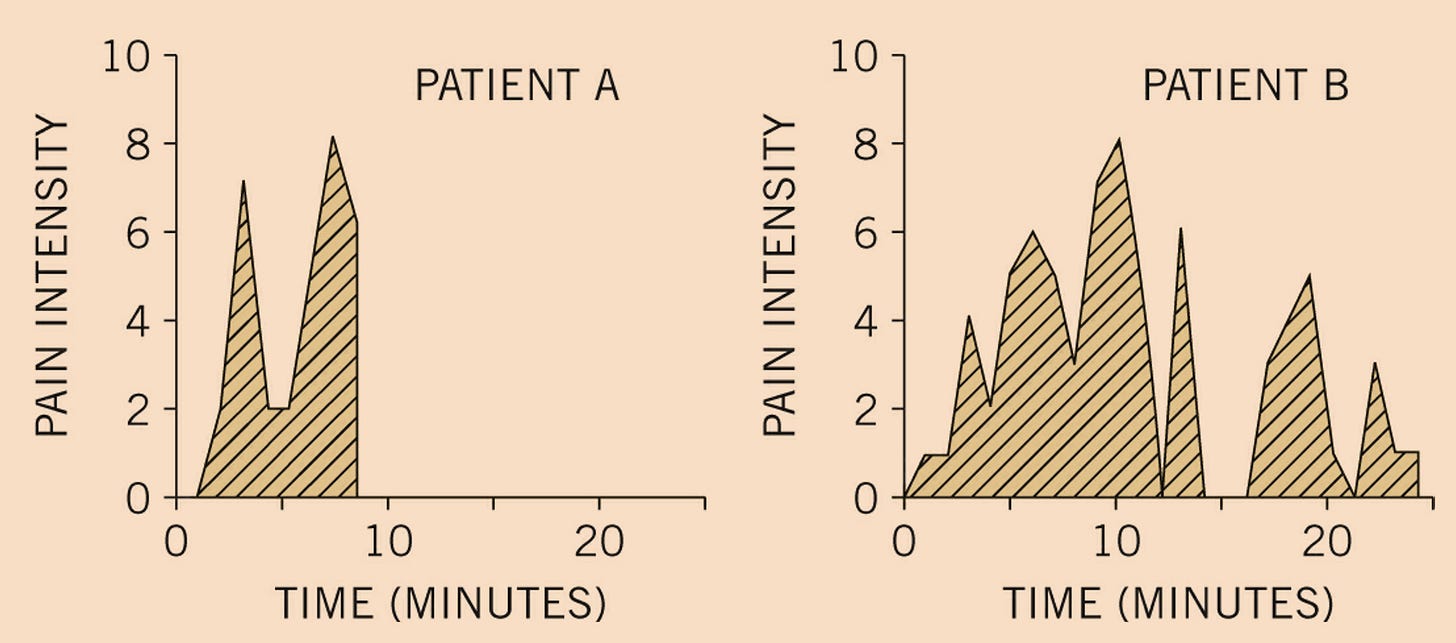

"The experiencing self and the remembering self… do not have the same interests." As demonstrated by – what else? – patients undergoing a colonoscopy examination. (Who says behavioral science isn't fun?) Every 60 seconds each patient evaluated their pain on a 1-to-10 scale.

diagram from ‘Thinking, Fast and Slow’ (Chapter 35)

Obviously, we would prefer to be Patient A. Each of the two treatments varies between 2 (uncomfortable) and 8 (jolly painful), but Patient B's one goes on for three times as long, a distressing 24 minutes of poking about.

"But the automatic formation of memories – a feature of System 1 [the intuitive mind] – has its rules." And when asked to assess the experience after it was all over, Patient A rated their experience even more negatively than Patient B.

Detailed, randomised experiments of people dipping our hands in ice-water were needed to work this one out. The old Brownie Box camera had just eight shots on a roll; but Associative Memory makes do with only two. It records the worst moment of all, and also the end. Nothing else - not how long it went on, not the average pain level. Just the two snapshots. Both Patient A and Patient B suffered up to agony level 8: but A finished off at 6, and B had a gentle ending at only 1. Averaging, Patient A remembers the experience as a whole at a 7, B at only 4.5.

Nowadays, the examinee receives not just anaesthetic but an amnesiac drug as well. Leading us to ask: which would you prefer? A moderately painful medical procedure (let's say, 30 minutes at misery level 6), or an absolutely agonising one (2 hours at level 9) which you wake up afterwards not remembering it at all? Luckily for you I'm not a behavioral scientist, so I'm not requiring you to answer that one…

But sometime in the next month or two, you'll open a magazine or a screen and see – something inspiring and exciting. A guided trip up Everest, the Scottish Coast-to-Coast, a six mile swim along Windermere.

Will you think it over in your rational mind, assess the expected levels of pain?

Will you heck.

Coast to coast across Scotland with a big backpack. That’s just got to be jolly good fun...

It's all such jolly good fun for about seven hours then a "Why did I ever sign up for this?" Then, " I think I'll drop out," then "I'll never do this one again!" Then there's only six miles to go and the trail sweep has staggering you in hand. You come in last and there's a few people taking down the finish site and you get a smattering of applause. The ambulance drives away (mandatory at some ultras) but at least you're not in it. A friend takes your photo and it shows a shambolic human wreck with a dazed gaped-mouth look. And yet you register for next year's running just as soon as registration is open!

This is a book I didn’t finish. Now, I feel the urge to pull it out again. The temptation of one of the LDWA’s hundred milers tugs at me occasionally, but so far I’ve managed to resist!