He doesn’t know what they climbed. It was black, and slimy, with rather a lot of plant life. It won’t have been more than Hard VS, because that was as hard as my Dad could climb. I’ve a feeling it might have been Creag a’ Bhancair, the steep, low crag round to right of the avalanche-prone Coire na Tulaich that’s the normal walkers’ route up the Buachaille. But the easiest route there’s E2, so maybe not.

Anyway, my Dad survived, to live on to the age of 99. Haston survived as well; but not so long.

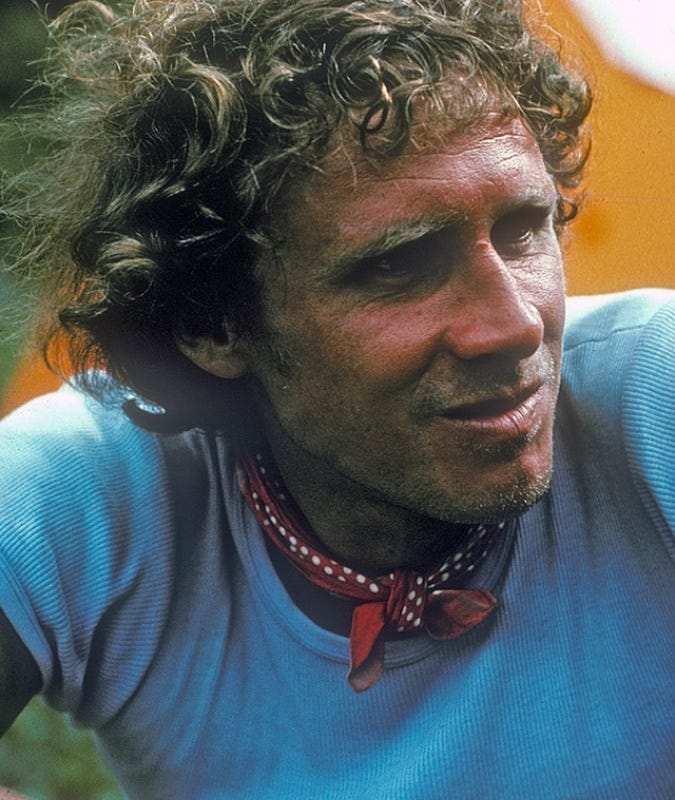

Haston was a full member of that great generation of 1960s climbers including Bonington, Doug Scott, Joe Brown, Don Whillans and Dr Tom Patey. They had the nice new nylon ropes and the use of nuts for protection. But what mainly made the difference was an increase in ambition, and an acceptance of danger and discomfort (not that the likes of Wintrhrop Young and WH Murray were wimps in any way). Helped by the strength and fitness that came from their day-jobs (many of them apart from Bonington, Patey) as manual labourers.

Do bad people make the best climbers? Looking at that lot from the 1960s, the answer’s no. Doug Scott was by temperament one of the flower children: he devoted his later life to grass-roots development work in the high valleys of Nepal, schools and medical centres. Bonington (leaving aside his habit of high-altitude mountaineering) is sound, sensible and well organised. Joe Brown was beloved by everybody, and people liked Tom Patey too.

On the other hand… Don Whillans, nicknamed The Villain: egotistical and untrustworthy. And Haston, a thoroughly nasty piece of work. At the low-point of his life, he drove back drunk from the Clachaig Inn in Glen Coe, in a car with defective headlights, and ran over and killed a young man called James Orr who was walking towards the youth hostel. Haston got two months in jail for that.

He was out in time to take part in Bonington’s Old Man of Hoy TV spectacular: Haston put up new route on it on live TV. And the same year, 1966, he was a lead climber on the Eiger Direct. This was a winter climb as a way of avoiding the rockfall, using siege tactics, climbing the face bit by bit setting up fixed ropes, with the following climbers using metal clamps (Jumars) attached to them.

Haston had just jumared up the fixed rope to the Spider icefield: John Harlin, the American expedition leader, was following him up when the rope finally frayed through.

The Clint Eastward film ‘The Eiger Sanction’ was mostly shot on the North Face itself. In an appointment every bit as sound and well-judged as last November’s election in the US, Haston landed the job of Safety Officer…

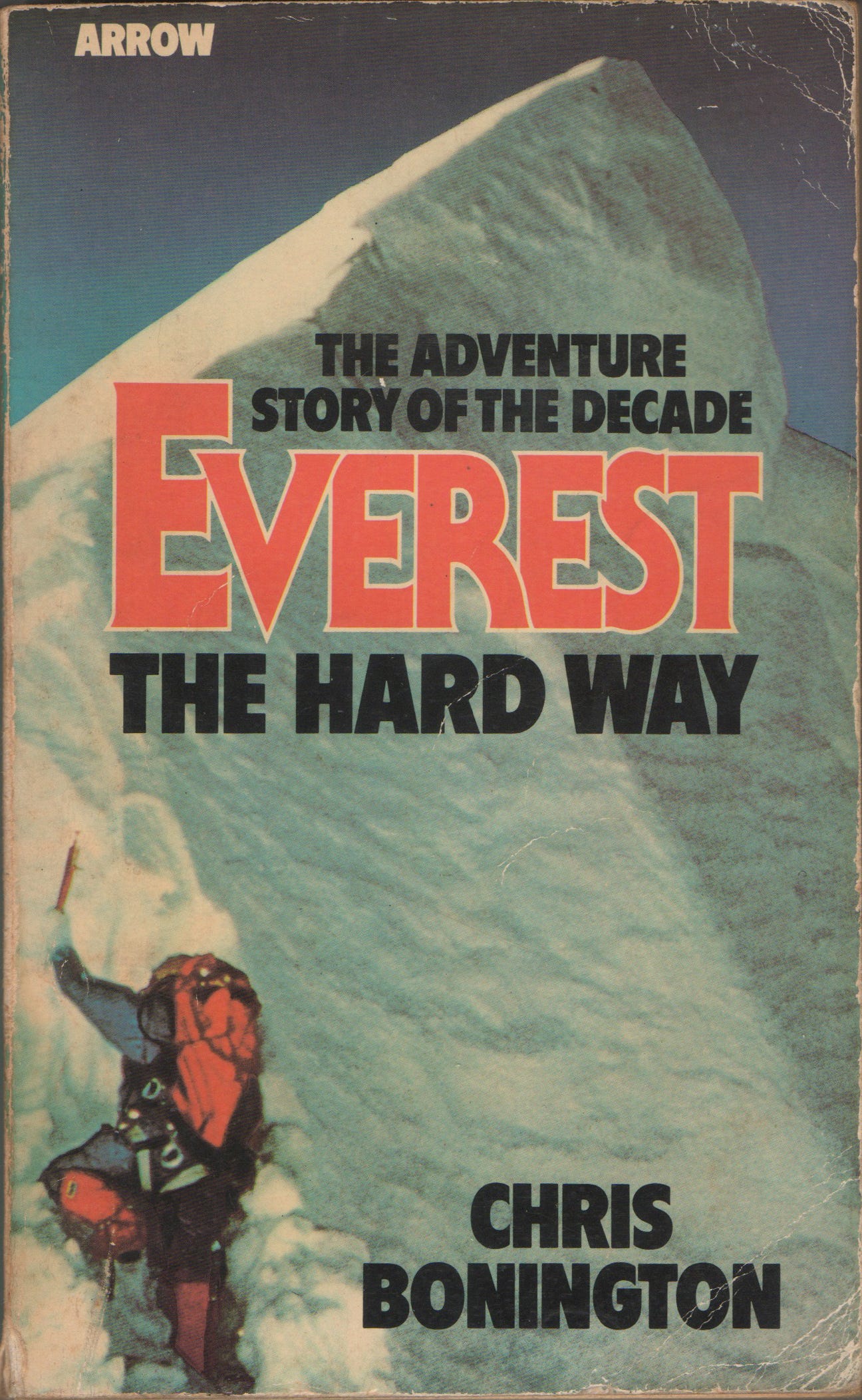

The Annapurna South Face expedition of 1970 was the first difficult route on the 8000-ers – all previous having been ‘easiest way up and see if we can get down still alive. It used a very strong team of climbers, all the good ones pretty much, plus Bonington’s organization: Sandhurst training, plus skills of delegation learned on two earlier expeditions. Haston and Whillans festered in the high camp for a week of bad weather being resupplied from below; then pressed upwards, unroped, to the summit.

Less well organised was Dhyrenfurth's International Expedition to Everest’s SW Face and West Ridge.It involved, to maximise the sponsorship, 33 climbers from 13 different countries: but again with Haston and Whillans among the leads.

The expedition was marked by indecisive leadership from someone who wasn’t Bonington, and consequent poor morale. At Camp Two above the Khumbu Icefall, Haston and Whillans conduct a personal sweepstake on which expedition member was going to be the first to die.

On the much better (because Bonington-led) 1975 expedition to Everest’s SW Face Haston was again a lead climber, this time alongside Doug Scott. The two of them went for it from the top camp, but deep soft snow meant they’d no chance of reaching the summit and returning. They went for it anyway, arriving at the top just in time for the sunset, then bivvied, without any overnight gear, in a snow hole near the South Summit. Scott was “wishing perhaps we had given more thought to the possibility of bivouacking, for we had no food and no sleeping bags…. I found myself talking to my feet.”

They both survived. For the time being…1

Two years later, and Dougal, now running his own ski school in Switzerland, wrote a novel that while only so-so in literary terms does express his view of the world. The cover of ‘Calculated Risk’ shows someone being knocked off a winter mixed route by some stonefall.

The protagonist, ‘Jack’, gets together with a girl Judy who “was that unusual combination: a good-looking woman and a climber. Not only was she good-looking, she could easily have been called extremely attractive…. smallish breasts.”

Jack solos a difficult new route (with one pitch of artificial climbing) in Glen Coe. He beats up some annoying bike boys at the Clachaig Inn. Back in Switzerland at his ski school, he outruns a powder-snow avalanche above Leysin village. And then heads towards the unclimbed west face of the Grandes Jorasses.

For the ski-slope episode: “There was a slight danger of avalanche but it did not look as if the whole slope would go, and Jack reckoned he could outrun any small slides… ‘Ah well,’ he muttered to himself, ‘can’t be right all the time. The rest of the run should be safe.’ ” He reaches the bottom needing a beer after the “exhilaration of the descent”.

The avalanche slope is at a high angle for powder snow; that’s the whole point. But the description itself is curiously flat and emotionless. Because Haston himself was curiously flat and emotionless? But maybe it’s just his incompetence as a novelist. It isn’t enough to simply say the avalanche happened and leave the rest to the reader; you’ve got to work out ways to convey the terror and the exhilaration via emotive language, imagery, etc – there’s s plenty of guidance elsewhere on the Substack platform…

But the issue matters because, in this chapter, Haston is describing, exactly, his own death. Because that was how it ends: ski-ing that same avalanche slope, above Leysin village, just a few days after he’d written ‘The End’ on his autobiographical novel.

Maybe, like Jack in the novel, Haston really did think ‘”there was a slight danger of avalanche but it did not look as if the whole slope would go, and [he] reckoned he could outrun any small slides” – after all, mountaineers think things like that all the time, and quite often they’re correct.

But equally maybe, an avalanche was exactly what Haston wanted. The exhilaration of ski-ing out on top of a happening avalanche: maybe that had happened once, in an emergency situation, and he just wanted that excitement again.

But, for a climber like Haston, survival or dying is always somewhat random. The moment when ‘Calculated Risk’ turns into ‘Miscalculated Risk’…

Doug Scott, combining good judgement with a good dose of luck, survived to old age, dying in 2020 aged 79. Bonington, happily, is still around.

Nice. One thing you don't mention is that your two 'nasties', Hastone and Whillans, shared a very notable achievement, the South Face of Annapurna. Not sure how well they got on—Bonington's book is a little reticent on this.

And it produced this memorable radio exchange:

Bonington: Did you manage to get out today?

Haston: Aye, we've just climbed Annapurna.

A very successful expedition marred by the death of Ian Clough very near the end.

Nice article. One quibble with the caption to the opening pic - Lagangarbh is the white building in the midground and the picture is likely taken from the Devil's Staircase.