Mountains in Manga

Mountain climbing. What’s it all about, why do we do it, and is a big peak really worth more than life itself? The best answers so far come from Japan by way of France and Netflix. [1200 words 5 mins

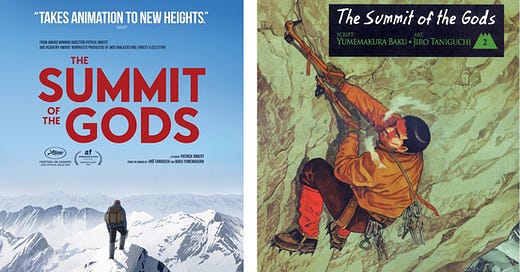

Summit of the Gods (Patrick Imbert 2021: on Netflix)

Mountain climbing is exciting. It’s about serious matters of staying alive and dying. It happens in the world’s most scenic spaces, and involves significant social interactions along the 9mm nylon climbing rope.

So how come there are so few mountain-climbing stories? Almost no novels1, just a few full length feature films, not even any epic poems. When it comes to novels, the sport seems to be mainly baseball: in film, it’s all about boxing. Yes, even the promising ‘Rocky’ series turns out to be entirely about chaps punching each other in the face…

Documentaries, yes. Memorable mountain memoirs, plenty of those. But straightforward, made-up stories? Not so much. And yet, lingering among the high back valleys of Netflix, is the film that shows it can indeed be done. You just have to be either French or Japanese…

Le Sommet des Dieux, The Summit of the Gods – that title, actually, being the weakest thing about it; no gods were bothered during the making of this movie. It came out in 2021, directed, in French, by Patrick Imbert. But you can get it on Netflix dubbed into English if you like it like that, or with subtitles in either language. (Given I’m hoping to hit the Vanoise this summer, I watched it in French with French subtitles.)

But before it was a French film it was a set of Japanese manga comics; and before that, it was a novel by Baku Yumemakura. Have you ever heard of Baku Yumemakura? He’s a 20-million selling2 author of 280 books, of which just one has been translated into English. And as you may already have worked out from the screenshots, the resulting film is an animation: hand-drawn in animé style from the work of Manga artist Jirô Taniguchi.

Marcher. Grimper. Grimper encore. Toujours plus haut. Et après…

The film has a nice straightforward plot. As the inciting incident, journalist Makoto Fukamachi comes to suspect that reclusive climber Habu has come into possession of George Mallory’s camera. That’s the one from Everest in 1924, the one that might show whether Mallory and irvine did actually make it to the top. That Vest-pocket Automatic then takes the classic role as the MacGuffin: the small object inserted into the plot so that all the characters can chase after it.3

It’s the archetypal story of the driven and talented climber called Habu, who takes on a difficult route (a fictional Devil’s Wall, in winter conditions) to gain credibility and sponsorship. Habu’s climbing rivals die; his young second dies after a rope-cutting moment inspired by Touching the Void. And then he sets off to solo Everest, by the South West Face, the one climbed by the Bonington-led expedition of 1975.

Baku Yumemakura is indeed a climber and trekker, as well as various other adventure sports: his massive output includes photo books of Nepal along with SF and fantasy. Illustrator Jiro Taniguchi hiked to Kathmandu to research the series. He is not a climber, though he has produced ‘Walking Man’, a meditative manga about a stroll through Tokyo (worth seeking out!)

The climbing sequences are set in the 1990s, which some consider a golden age in terms of gear and climbing generally4: front pointing, nice chunky carabiners and pitons; the two climbers sitting on a stone at a litter-free Everest Base Camp; the two then climbing into the solitary spaces of the Western Cwm – which these days will have a queue of commercial climbers along it from the Icefall all the way up to the South Col.

And the climbing technique is spot-on. The sound of a piton going into rock or ice. What It feels like in a bivvy when a large stone comes down directly over the tent – Recule tes jambes, pull your feet in closer! The way you tap your crampon with the iceaxe to knock off the balled-up snow before taking a run at a crevasse.

The animation is almost photo-realistic; but with a touch more landscape romance than you’d get even with helicopters, drones and ‘Free Solo’ type camera work; and with a fine phantasmagoric storm+anoxia sequence. The Walker Spur, Everest; but also Namche Bazaar, Kathmandu and street scenes of Tokyo. The two tents, yellow-orange, illuminated from within, under the huge mountainscape of the Western Cwm and the stars. The lights go out. One light comes on, a muttered oath. And Fukumachi comes out to pee under the stars for that familiar moment of pissing awe in the middle of the night…

And all the way through, the film is addressing the big questions of climbing. Why? Where’s the fun in it? is that amount of fun really worth dying for?

Habu avait raison. J’avais la réponse au mystère Mallory, mais pourtant ça suffisait pas. Pour quelle raison aller toujours plus haut? Être le premier? Pourquoi risquer la mort? Pourquoi faire une chose aussi vaine? Aujourd’hui, je sais. Je sais qu’il n’y a pas besoin de raison. Pour certains la montagne n’est pas un but, mais un chemin. Et le sommet, une étape. Une fois là-haut, il n’y a plus qu’à continuer.

Habu was right. I had the answer to the Mallory mystery, but in the end that wasn’t enough. What’s the point of it, the going ever upwards? To be the first? Why risk death, just for that? Why do anything so pointless? Today, I know. I know that there’s no need for any reasons. For some of us the mountain isn’t a destination, but a path. And the summit, no more than a staging point. There’s nothing for it but to carry on.

So, is ‘Summit of the Gods’, with its simple but emotionally rich storyline, its superb hand-drawn scenery: is this the good one for your dear family members, to show them what mountaineering’s all about? Unfortunately not. Not unless you really do want to acclimatise them to the idea of your likely death...

But if you’re a mountaineer yourself, then you may well be fed up with the tundra-free settings of Baby Reindeer, bored with the simplistic sports of Squid Game. Then ‘Summits of the Gods’ offers the best answers so far to the unanswerable question of why we go up big hills.

And it also looks extremely pretty.

This post on UKhillwalking does manage to unearth five works of climbing fiction, none more recent than 1973 and one of them in French.

[That’s exactly twice as many as cosy-crime author Richard Osman]

MacGuffin: term popularised by Alfred Hitchcock, applied to the Maltese falcon in the same-named film, the letters of transit in Casablanca, the cash-filled briefcase in Pulp Fiction, the various horcruxes, deathly hallows and Gryffindor swords in Harry Potter, possibly even the lighthouse in Virginia Woolf’s ‘To the Lighthouse’. This video isn’t really helpful in explaining the concept

The actual golden age of gear, the perfect balance between really-is-too-risky and oh-so-much faffing-about, was the time of early nylon ropes, just after the development of nuts and just before that of camming devices. And you can’t argue with me over that, any more than you can when I point out that the years 1967-70 were the all-time peak for popular music.

Thank you for the recommendation.