Mind has Mountains

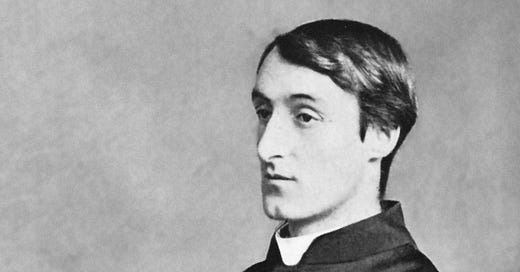

Gerard Manley Hopkins could have been the greatest outdoor writer of the Victorian age. But, for religious reasons, wasn’t. [1300 words 6 mins

O the mind, mind has mountains; cliffs of fall

Frightful, sheer, no-man-fathomed.

Gerard Manley Hopkins, 1885

This week was going to be about whether or not George Mallory got up Everest in 1924. But I’m just about to receive a brand new book about Everest 1924 to review, so I’m leaving George until next week when I’ve read it. In the meantime, one of my perhaps-less-popular poetry posts.1

One thing we know about writers is displacement activity: our habit of ignoring what we ought to be working at and doing something else instead. Given some important task like the tax return, or fetching in the firewood, or a magazine article with a two-day deadline: that’s when I click the top right corner of my desktop, and write five hundred words about Coleridge visiting the Moss Ghyll waterfall.

And the name for my displacement-activity? It’s called ‘Mountains of the Mind’. Well, it was called that until 2003, when Robert Macfarlane pinched that title for a book of his own about the early history of climbing.

When I say Macfarlane pinched the title, I don’t mean for a minute that he pinched it from me. No, we both pinched it from a poem by Gerard Manley Hopkins (1844-1889) – a poem that’s actually not about mountains at all.

Hopkins was born into a respectable professional family: his father was British consul-general in Hawaii. And up to the age of 24, Hopkins was becomng one of the greatest English poets of the natural world. This despite the fact that his natural world was the suburbs of north London, plus some conventional holiday trips to Wales and the Alps.

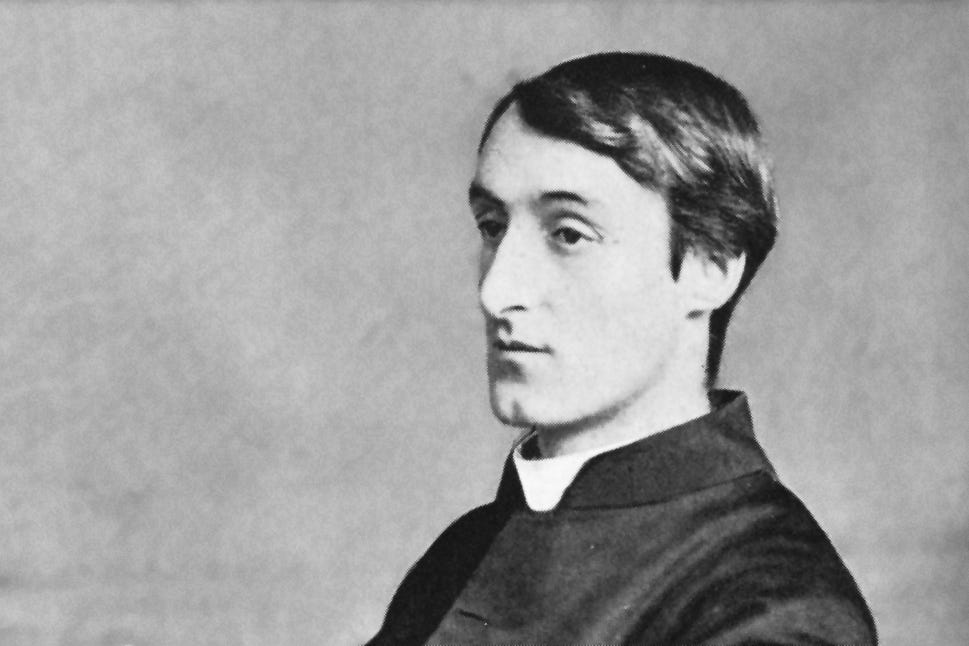

Here he is describing the glaciers (now so much shrunken) of the Bernese Oberland, with close observation of nature learned from Wordsworth and John Ruskin, but a standpoint that’s the busy tourist terrace at Kleine Scheidegg.

There are round one of the heights of the Jungfrau two ends or falls of a glacier. If you took the skin of a white tiger or the deep fell of some other animal and swung it tossing high in the air and then cast it out before you it would fall and so clasp and lap round anything in this way just as this glacier does and the fleece would part in the same rifts: you must suppose a lazuli under-flix to appear. The spraying out of one end I tried to catch [in his sketch-book] but it would have taken hours: it is this which first made me think of a tiger-skin, and it ends in tongues and points like the tail and claws: indeed the ends of the glaciers are knotted or knuckled like talons.

At the Baths of Rosenlaui – the gorge below the glacier northeast of Grindelwald, Bernese Alps, 1867, pencil drawing by GM Hopkins

Hopkins grew up pious Church of England. But in 1868, aged 24, he converted to Catholicism: a religious break which involved also a total break with his own family. He entered for the Jesuit priesthood, and burned all his poems. Luckily they survived, in copies he’d sent to fellow-poet Robert Bridges. And after a seven-year break, his sense of sin abated somewhat and he did return to poetry.

If he wasn’t really a nature poet, Hopkins wasn’t really a Victorian one either. His language is harsh, jagged, lumpy as the Borrowdale Volcanic rocks of the Lake District which he seems never to have visited. Hopkins is a world away from the smooth, complacent rhythms of Tennyson, Robert Browning, Matthew Arnold – and close kin to Dylan Thomas, Hugh Macdiarmid, even Sylvia Plath. Which makes him a very early 20th century poet who just happened to live in the 19th Century.

Inversnaid

This darksome burn, horseback brown,

His rollrock highroad roaring down,

In coop and in comb the fleece of his foam

Flutes and low to the lake falls home.

Inversnaid waterfall, with the footbridge used by the West Highland Way

In September 1881 Hopkins was working as a priest in the grim, industrial suburbs of Glasgow. From there he took the tourist excursion by steamer from Balloch, aware perhaps that the Wordsworths and Coleridge made the same visit in 1803. He spent just two hours ashore. He visited the waterfall and the footbridge, wandered a little way up the road towards Loch Katrine, then back on the boat again.

A windpuff-bonnet of fáwn-fróth

Turns and twindles over the broth

Of a pool so pitchblack, féll-frówning,

It rounds and rounds Despair to drowning.

The full poem can be read on hopkinspoetry.com. The accent marks indicate his trademark ‘sprung rhythm’: four stressed syllables in a line which can otherwise be as long as he wants. And the final stanza, its environmental appeal so beloved of today’s Lomond & Trossach National Park:

What would the world be, once bereft

Of wet and of wildness? Let them be left,

O let them be left, wildness and wet;

Long live the weeds and the wilderness yet.

Less often quoted on the LDNP’s interpretation boards is that pitchblack pool, sucking downwards like Hopkins’s own misery. Today, his depression would be identified as a mental health issue. But for Hopkins, this was sin. And sin of the worst sort, as he blamed himself for questioning his belief in God; as well as confronting his own homosexual desires. There was also his job teaching at Stoneyhurst, where the horrid school boys made fun of him.

Which brings us to the so-called ‘Terrible Sonnets’.

No worst, there is none. Pitched past pitch of grief,

More pangs will, schooled at forepangs, wilder wring.

Comforter, where, where is your comforting?

Mary, mother of us, where is your relief?

My cries heave, herds-long; huddle in a main, a chief

Woe, wórld-sorrow; on an áge-old anvil wince and sing —

Then lull, then leave off. Fury had shrieked 'No ling-

ering! Let me be fell: force I must be brief.’O the mind, mind has mountains; cliffs of fall

Frightful, sheer, no-man-fathomed. Hold them cheap

May who ne'er hung there. Nor does long our small

Durance deal with that steep or deep. Here! creep,

Wretch, under a comfort serves in a whirlwind: all

Life death does end and each day dies with sleep.

Posted as a seminary student to central Wales, GMH did enjoy a bit of hillwalking. But no, these mountains are not much to do with Snowdonia at all. The grim cliffs exist only within his own tormented mind. “Huddle in a main” evokes frightened sheep; “creep Wretch under a comfort serves in a whirlwind” could be a recollection of foul-weather moorland hiking man King Lear.

By comparison any mere cliffs of the real world will appear insignificant – the north face of Ben Nevis

The Jesuits asssigned him to the grimmest industrial cities as teacher: Sheffield, Manchester, Glasgow. Hopkins died aged 44 in Dublin of typhoid fever, caused by polluted drinking water.

That Nature is a Heraclitean Fire and of the comfort of the Resurrection (1888).

And yet, before the end, he did regain his sense of God’s glory and closeness: a glory seen in and through the natural world. Even if, in his city surroundings, that world is reduced to the clouds seen above some elm trees. “Heraclitean Fire” refers to the early Greek philosopher Heraclitus2 whose Fire is the essence of everything. “Million-fuelèd, | nature’s bonfire burns on:” it’s the fire from which the world is created, constantly renewed, and which ultimately is going to destroy it. The full poem is at www.poetryfoundation.org; this is just the ending of it. Not the easiest read – “Words strain, Crack and sometimes break, under the burden,” as TS Eliot said3.

Cloud-puffball, torn tufts, tossed pillows | flaunt forth, then chevy on an air-

Built thoroughfare: heaven-roysterers, in gay-gangs | they throng; they glitter in marches.

Down roughcast, down dazzling whitewash, | wherever an elm arches,

Shivelights and shadowtackle ín long | lashes lace, lance, and pair…

In a flash, at a trumpet crash,

I am all at once what Christ is, | since he was what I am, and

This Jack, joke, poor potsherd, | patch, matchwood, immortal diamond,

Is immortal diamond.

Autumn waterfall below Blackwater Reservoir, Kinlochleven

And, in his Manchester city park, is such nature-based religious ecstasy so different from Coleridge on Scafell, Bill Murray on Ben Nevis at the top of Tower Ridge, Leslie Stephen on Mont Blanc?

All the best ‘how to Substack’ Substacks say to post what you care about, rather than what’s going to attract those alluring love-hearts, restacks and new subscribers!

They told me, Heraclitus, they told me you were dead,

They brought me bitter news to hear and bitter tears to shed.

I wept as I remembered how often you and I

Had tired the sun with talking and sent him down the sky

By another unhappy gay schoolmaster, William Johnson Cory, thrown out of his job at Eton under a cloud. But according to the Internet, this is about a different Heraclitus.

Four Quartets: Burnt Norton, part V

Words strain,

Crack and sometimes break, under the burden,

Under the tension, slip, slide, perish,

Decay with imprecision, will not stay in place,

Will not stay still.

As a poet, Hopkins was a good artist. 😁

I'm also struck by the link between mountains and religious feeling. Wasn't it Hamish Brown who said (I'm quoting from memory) "Pity the poor atheist with no God to praise!"

And yet lots of us atheists seem to get along fine.