John Milton and me

How hard will it be to maintain this Substack feed after becoming a partially sighted person? Poet John Milton managed it okay. [1400 words, 6 mins

When I consider how my light is spent

Ere half my days in this dark world and wide,

And that one talent which is death to hide

Lodged in me useless, though my soul more bent

To show therewith my Maker and present

My true account, lest he returning chide.

“Doth God exact day-labour, light denied?”

I fondly ask. But Patience, to prevent

That murmur, soon replies: “God doth not need

Either man’s work or his own gifts: who best

Bear his mild yoke, they serve him best. His state

Is kingly; thousands at his bidding speed

And post o’er land and ocean without rest:

They also serve who only stand and wait.”1

In March of 1652, John Milton, civil servant and the leading poet of his time, lost the sight of both his eyes. He was 43 years old.

In trying to make sense of his condition, he turned to the Bible: in particular to the parable of the talents in Saint Matthew’s gospel Chapter 25. In its original meaning, a talent is a sum of money equivalent to 6,000 silver denarii: a tidy sum. As working capital, the Master leaves each of them with a sum of two talents. On his return he asks the servants what has become of the money.

“I looked after it ever so carefully,” says servant number one. “I buried it in a secret place in the ground and now that you are returned, here are your two talents back again. Slightly dirty but they will shine up nicely with a bit of hot water.” “Oh,” says the Master: “and you, servant number two: how have you got on with your two talents?”

“Well, Master: as you know, the value of Investments can go down as well as up. I purchased a small grinder mill which I used to mill some olives and sell the resulting oil. Which unfortunately happened to be on the sleeps of Vesuvius and you know what happened up there... What was left over, I put it into bitcoin. And the result is now that your two talents have turned into five! Here you go! Maybe a small commission coming my way?”

“Well done thou good and faithful servant! Yes, you get your small commission and a place in heaven when you die. As for the other guy, it really won't do,” and given the nice convenient hole that we see he has already dug, well. It's obvious what's going to happen to him.

The modern meaning of the word talent derives directly out of St. Matthew. A talent for hill running or baking cupcakes or painting chapel ceilings upside down comes to you direct from God and it is your duty to use that talent in his praise and service.

Which Milton, after a few years of lightweight verses about classical nymphs and suchlike, getting his eye in as it were; service to Oliver Cromwell's Protestant government as his Latin language secretary (unless that was Andrew Marvell? I know it was one of the two.)

But now in his blindness, the best he can do is 14 lines on it in the tricky Petrarchan rhyme scheme, composed in his head and written down on some paper in the hope that somebody else hadn't already written on that particular piece, and there was enough ink in his quail pen to allow the result to be legible to the world. (At least he didn't have to deal with the way Android's TalkBack inserts snatches of its own instructions and conversation into the written text – a feature that would really mess up the Iambic pentameter).

But perhaps he dictated his poem to one of his daughters. Her heart sinking at that final line with its image of a finely dressed footman standing around at the edge of the World's banquet with absolutely nothing to do in exchange for a very small salary. But all that poor Milton had to wait for was his own death 27 years later.

Two years ago, following a benign tumour the size of a small mouse on my pituitary gland, I lost 2/3 of the site of my left eye. Two weeks ago for no obvious reason the vision in my right eye started to fade away from the outside edge, inwards towards my nose; and five days later I had no clear vision at all. (The couple of Substack posts that you might have seen since then were already scheduled in advance.) But compared with John Milton, I have two advantages. As an atheist, I do not have to spend time trying to work out what the meaning of all this can be. No, it's not a punishment for my manifold sins and wickedness; nor is it a specially offered opportunity for my friends to deploy compassion. Also, I am the owner of a an Android smartphone with various clever features. So that while there is an obvious opportunity to sit around gazing at the fuzzy trees and feeling miserable, there is also an opportunity to study something called TalkBack and discover that it is still possible to send and receive emails, WhatsApp, text messages, the audiobook of Northanger Abbey (my usual go-to in times of stress). And so I suddenly found myself with a lot to do and plenty to think about....

Anyway, I've never been able to master that tricky Petrarchian sonnet form at all. Let alone the clever enjambment on lines 3 to 13, did you spot it? the way none of the sentence endings occur at the same place as the line endings, conveying the poor poets sense of bewilderment in perfect verse

Because, it is a strange fact of The Human Condition (at least as experienced by some of us) that when composing a Petrachan sonnet about one's blindness that has just come on, you are thinking about the Petrarchan sonnet and not about the blindness. And when waiting around in the waiting room at ophthalmology, here’s an interesting thing. We think that our eyes are a transparent window on the world. We're wrong about that, of course, the sense impressions that present themselves as beings in the outside Universe are entirely created by us within our own brain. And this becomes rather obvious in the ophthalmology waiting room. If I look a few degrees to the right of the person with the black spectacles, that person's head is not visible to my damaged eye; and accordingly my brain fills in the space above their collar in the tasteful beige texture of the wall on either side. Even, with a little extra care, I can construct a blue-suited health worker's blue suit striding across the scene without any health worker inside it at all.

Which, you know, does just make a topic for a short Substack posting.

Mind you, John Milton did do rather better than that. After becoming totally blind, unable to see what blotches and scratches he was creating with his quill, or possibly by dictating (in the absence of the smartphone that wouldn't be invented for another 300 years yet) to that possibly grumpy daughter, he wrote the nearly 11,000 lines of Paradise Lost.

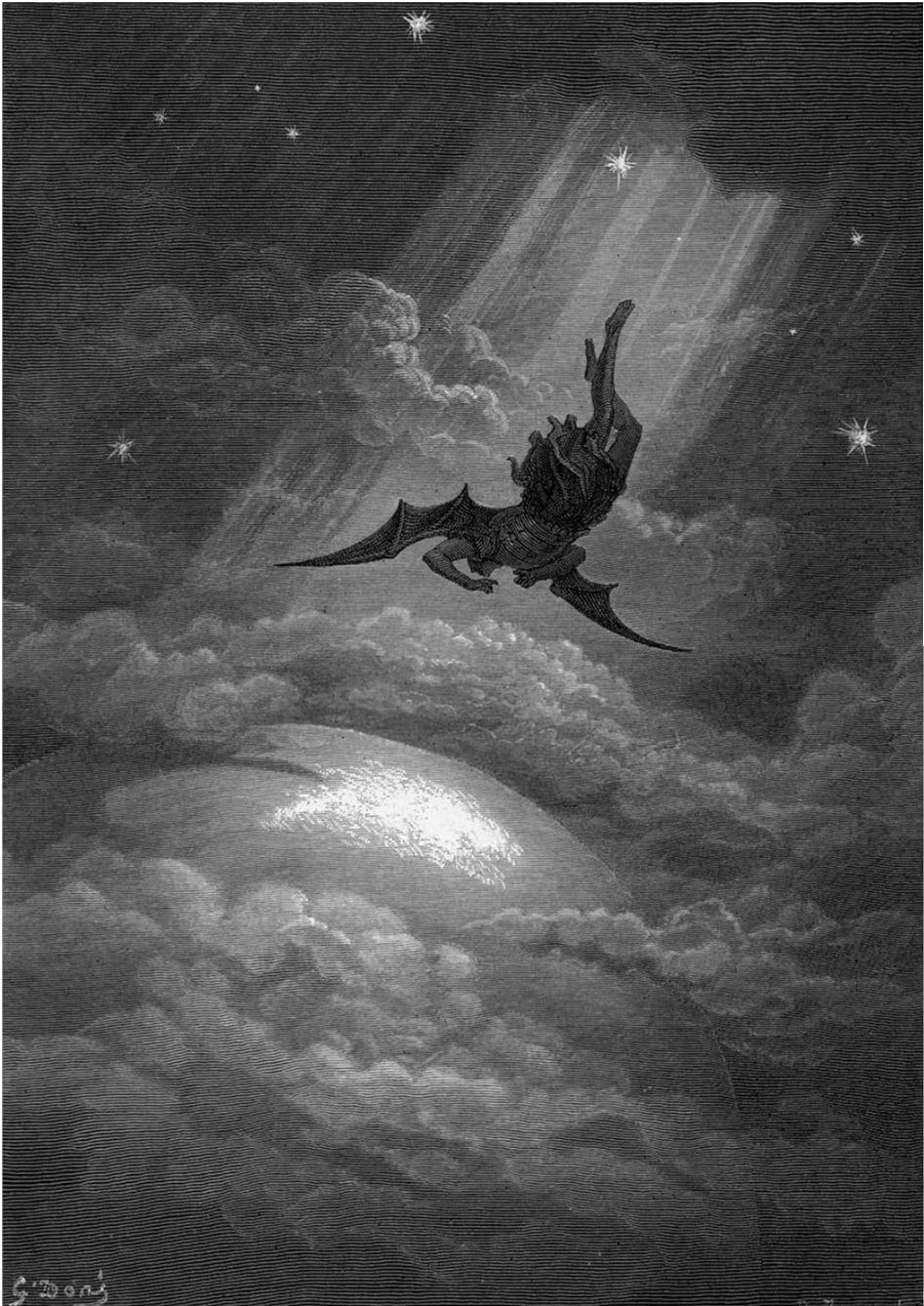

And the space behind his unseeing eyes, filled with the shapes of imagination, becomes the “darkness visible” of the pit filled by Satan and his fallen angels.

No light, but rather darkness visible

Serv’d only to discover sights of woe,

Regions of sorrow, doleful shades, where peace

And rest can never dwell, hope never comes

That comes to all...Paradise Lost Book 1 line 63.

The intention of it all being, in his own words, to explain the ways of God to man.

Though it does have to be said that he had that usual “difficult second sacred epic” issue with the follow-up, Paradise Regained.

My own eye problem is still being investigated - and in case you were wondering why this post has so few interesting auditory misprints in it, a one week zap of powerful steroids has sharpened things up so that I can now do some straight editing with an eye and a finger. Shall I succeed in continuing to provide reasonably intelligible Sub-stack content?

Watch this space.

Or else, of course, listen to this space using the TalkBack facility on your Android smartphone.

“Fond” soft-headed. “I am a very foolish, fond old man” - King Lear. There’s often a comma at the end of line 6 ( “chide”) but the question in line 7 is Milton’s, not God’s.

Coming to terms with losing one's sight, even a portion of it, takes courage and resilience, and Ronald I know you have this in spades. You'll find ways around.. and ways through... just as you do when you're out and about exploring.

I wrote about a holiday I took this year with people who are blind - I acted as a guide. It gave me a fascinating insight into how people manage.

And having nearly lost my own sight several years ago, needing cryosurgery to glue my eyeballs back together... I appreciate your concerns.

All the best.

Great that you're writing as lucidly as ever, Ronald. And I never knew that Milton wrote Paradise Lost when he was blind. Really inspiring! ✨️