Is basalt an ocean bottom rock?

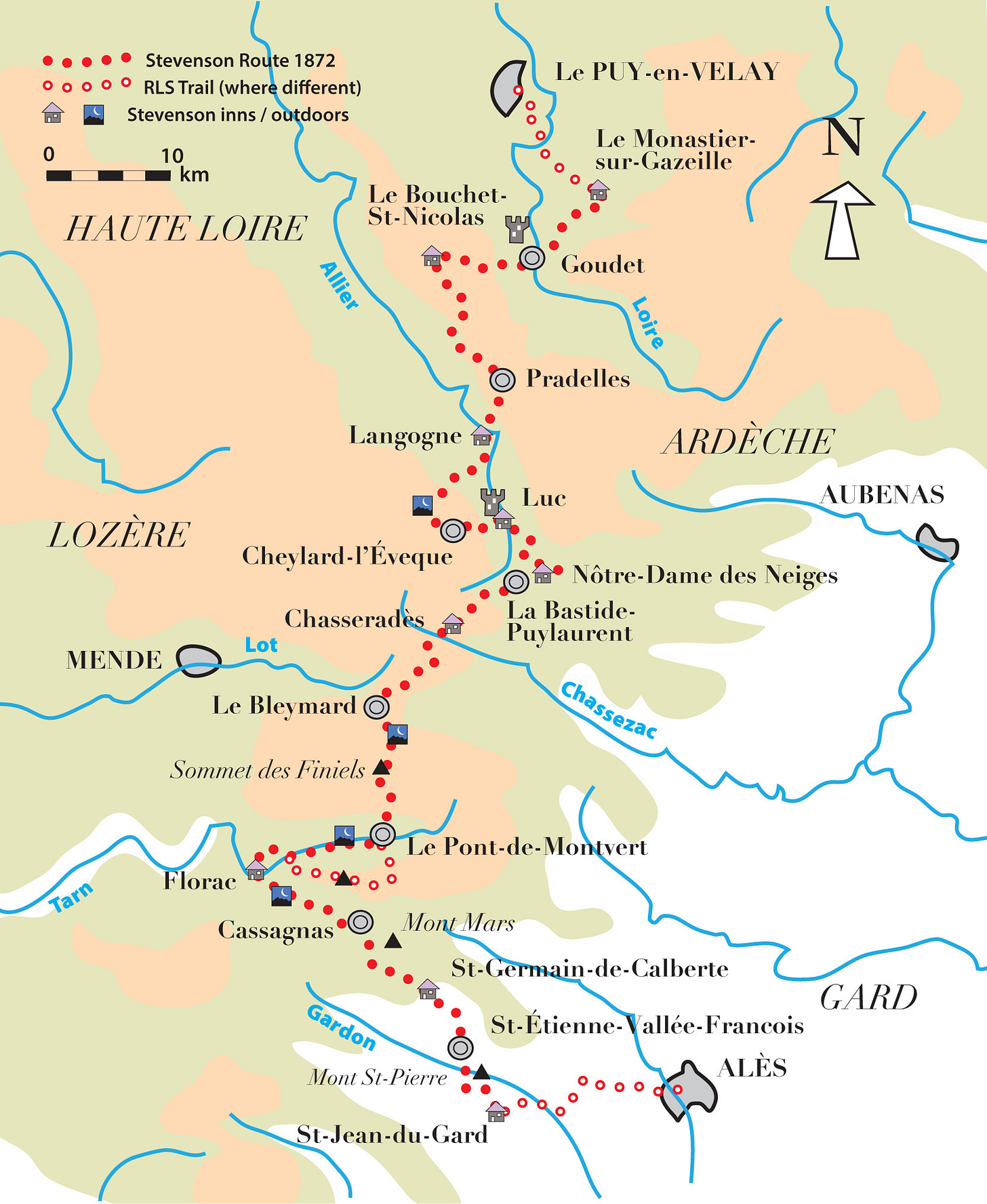

An Auvergne investigation along the Robert Louis Stevenson Trail [1900 words 7 mins

For the first two days into the Robert Louis Stevenson Trail, I’m passing through complicated farmland. The brown-to-black cottages with stone slab roofs seem to have grown straight out of the bedrock. The steep little street at St Martin is surfaced with flattened cowpats; above a café with rattly tin tables rises a church with a high false front like a castle cut into quarters and distributed around the parishes.

Not being encumbered with any donkey called Modestine, I’ve been walking Robert Louis Stevenson’s Trail too quickly. I’m at Le Monastier in time for a late lunch, but the Modestine-donkey-themed guesthouse won’t open till four. I pick up that late lunch at the supermarket, and dine in a bus shelter in the rain.

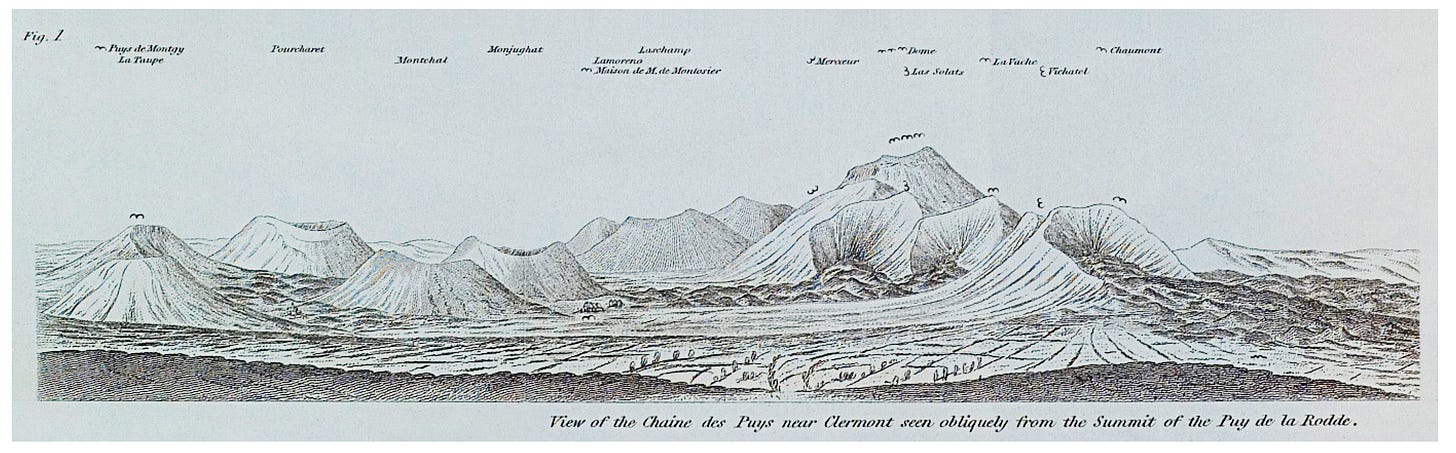

On the second afternoon I come up a stony donkey-path into the high brown plateau of the Auvergne. Fields of the famous brown lentils are on either side, wide under the sky. Scattered across the scenery are little rounded humps of hill, each one covered in chestnut trees, each one shaped much the same as the road-flattened cowpats of the villages below.

It doesn’t look like a place where one of the mysteries of the Earth was to be unveiled. But it is.

Sandstone is made of sand, and sand is eroded out of some earlier sandstone. But it all has to start somewhere. And, back in the late 1700s, James Hutton in Scotland and Abraham Gottlob Werner in France were looking at two sorts of stone in particular: granite, and basalt. Granite is clearly crystalline: regularly shaped small grains of mineral cemented together. And this black-brown stuff of the Auvergne, this is the basalt. See it also at the Giant’s Causeway or on Staffa, those regular hexagon shapes, presumably some sort of super-size crystals too. (I’m looking through the four eyes of Mr. Hutton here and Monsieur Werner. If you’re a 21st-century geologist you’ll already know the answers, and today’s post’s going to be a whole lot less exciting.)

Which brings us back to the RLS Trail. Because the fields suddenly tip over, and woods slant steeply down towards the wide, winding River Loire. There’s crags on the other side, and a castle – and yes, brownish-black crags, a mud-coloured castle. An ancient stone bridge, and a village, and a café, and a church. And behind the café, an big lump of bedrock: three times higher than the houses, twice as tall as the church, as if some great giant of the Plutonic underworld was sticking his thumb out to see if it had stopped raining yet.

Indeed, it’s the plug of an ancient volcano. And it’s not a one-off: there’s another behind the cathedral in Le Puy de Velay, except that one’s got the Virgin Mary posed on its top. In fact, there’s lots and lots of volcanoes in this bit of the middle of the bottom of France. Not all that ancient, either: one of them was erupting a mere 6000 years ago, which in geological terms is teatime last Tuesday.

So, there’s volcanoes. And there’s also that browny-black basalt, which was deposited underneath them on the floor of Noah’s ocean. Or else, alternatively, came out of those browny-black volcanoes themselves. Who knows?

Well, James Hutton, robust Scots farmer, for one. Every mountain range, with its crumpled and faulted rocks, has a big lump of granite lurking in the middle of it. Well, it does on Arran anyway. Clearly, the granite has pushed itself up from underneath, surging upwards like slow-boiling porridge. Basalt behaves the same, why not?

But Monsr. Abraham Gottlieb Werner, with his big Biblical name, knows better. These start-off rocks are made of crystals, and where do crystals come from? They assemble themselves out of stuff dissolved in water: you can do that yourself, in a jam-jar. This reveals the Earth to have been completely submerged in some ocean, but we knew that anyway, because it’s in the Bible.

An all-powerful god v. another all-powerful god

Abraham Gottlob named his theory after Neptune, the all-powerful god of the sea. James names his one after Pluto, the all-powerful god of geology or at least of the underworld. Each of the two theories has a great big hole in it. Neptunism: where did all that water go? Plutonism: where did all that heat come from?

James Hutton hauls his aching bum onto his horse1, and heads off up Glen Tilt to poke around the edges of the Cairngorm granite. Meanwhile, in France, here’s a middle-aged chap called Desmarest.

If you’re reading this via Gmail, the good folk at Google feel I’m going on a bit here and are about to chop off all the boring bits further down. To see them, can click on “View entire message” – or it’s on your browser .

Nicolas Desmarest, born in 1725, was academically gifted and mad about science but son of a simple schoolteacher and not sufficiently filthy rich to be an independent intellectual. So he got a job as the Inspector of Manufactures, making sure the Manufactures were far enough apart to allow him to crisscross anywhere he was interested in on horseback and on foot.

And he’s off to the Auvergne to Inspect the Manufactures check out the basalt bits.

What are they, these funny little cowpat hills made of crumbly black stuff like burned cinders? Did I hear you say volcanoes? Honestly, just take a look around you, See these cows, those lovely fields of lentils? Volcanoes, I ask you. What they are is, they’re leftovers from some Roman ironworks.

Okay, so they’re volcanoes. Because the big pointy Puy du Dôme, and the rest of the Chaîne des Puys, and that thumb sticking up beside the River Loire: those are volcanoes. And the rubbly stuff, that’s the burned-up rock from the underground coal fires that are powering them all.

Odd, though, that the colour of it matches that ocean-bottom basalt. So that the entire country comes out in the same cowpat brown, like a faded old etching by Rembrandt.

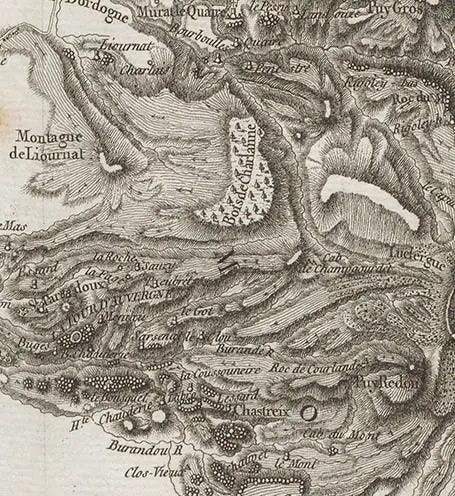

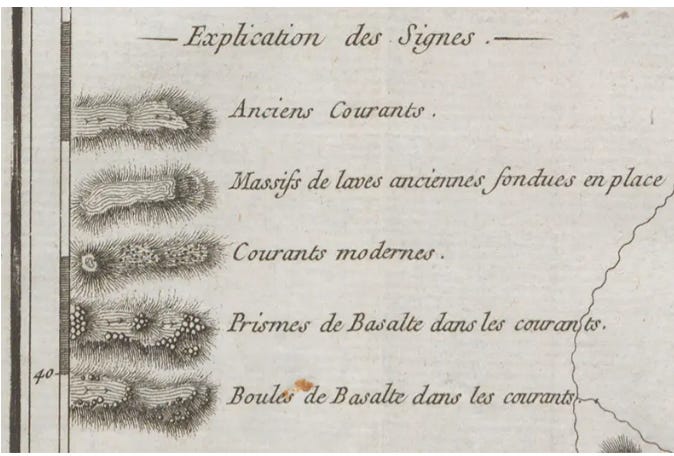

M. Werner and that other guy the Comte de Buffon and all the wise men of the French Academy, they can argue about this all day. But the quicker way is for M. Nicholas to head out to the Auvergne and make a map. (Not that much quicker: even with four helpers, it took him seven years.)

If the basalt came out of the volcanoes, then Mr. Hutton would have to be right, and Abraham Gottlob is wrong, and the very first rocks came hot from underground and not gently undissolving out of Noah’s ocean.

Which, after those seven years of mapping, it turned out that the cowpat brown basalt columns, and the cowpat brown rubbly stuff out of the volcanoes, did in fact join up. Were, indeed, pretty much the same stuff.

At which point Desmarest was admitted to the Academy of Sciences, Wernerism was overthrown, and all the Wernerist geologists blushed, shuffled their feet, published Desmarest’s nice map in Academy’s Memoirs for 1775, and admitted that was what they’d really thought all along.

Well, the first part, yes. But, oddly, Desmarest had his map didn’t make it into those memoirs. The Comte de Buffon had a much better idea about it all: an idea which he’d come up with the proper way, by sitting at home in his comfy reading room an idea already written up in seven leather-bound volumes of “Epochs of Nature”.

And the Comte de Buffon wasn’t any schoolteacher’s little boy. The Comte de B was the Treasurer in charge of commissioning the yearbook.

Coming up through the cowpat hills, Robert Louis planned to bivvy out beside the Lac du Bouchet. But by the time he’d got his luggage on his donkey, and his donkey on the road, and then got his donkey to actually move along the road … well, it was getting dark, and he couldn’t find the Lac du Bouchet anywhere among the lentils and the little hills. So he headed into the basalt-brown village of St Nicolas for the night.

And so did I, a hostel hewn out of chunky pine, and all the fun of a communal dinner speaking conversational French at the end of a 16 mile day. The little school, here, is staying open only thanks to the tourism boost of Robert Louis. Locally, though, Modestine the Donkey gets the lion’s share of the credit.

At daybreak I diverted to look for that lake. And found it – hidden inside one of the cowpat hills. Up a few minutes under the chestnut trees, and then a long wooded drop, and a crater hollowed out of the middle of the hill. A volcano, yes, but inside out: the lake a good fifty metres below the level of the surrounding country and the lentil fields.

With the superiority of my early 21st century geological expertise, I identify it as a phreatomagmatic ‘maar’ – an encounter between underground water and some more-than-red-hot lava. The interpretation board helps as well…

Desmarest’s map eventually made it into print. Which, along with James Hutton’s trip up Glen Tilt, confirmed it. No Noah. Hot rocks seethe upwards from underneath. And nowadays it’s obvious enough that basalt solidifies out of lava, and isn’t crystalline at all. Those columns are cooling cracks, like you learned in Standard Grade geography. Obvious enough – once you already know the answer.

Meanwhile the RLS Trail winds on southwards, down off the basalt, through the cramped mediaeval streets of Pradelles and up into some yellowish schists under woods of pine and chestnut; past the airy, empty monastery of Our Lady of the Snows; by timber tracks and donkey paths onto the blank, bare moorland at the top of the Cévennes; dipping to the ancient Pont de Montvert by slopes of bouldery granite and bright yellow broombushes; below some more schisty cliffs along the gorges of the Mimente; out above the juniper scrub to a hundred fading hilltops at Saint-Pierre; and down to St Jean du Gard. Which is where Modestine the donkey finally got too tired, and RLS ended his journey.

For my part, I travel not to go anywhere, but to go. I travel for travel’s sake. The great affair is to move; to feel the needs and hitches of our life more nearly; to come down off this feather-bed of civilisation, and find the globe granite underfoot or various other interesting geological formations2 and strewn with cutting flints.

Thank you to the readers who commiserated on the loss of eyesight described in last week’s post. To the surprise of my Consultant, 40mg of steroids has reversed the effect, for now at least; reading, typing, and hillwalking restored.

“Lord pity the arse that’s clagged to a head that will hunt stones.” – James Hutton

RLS actually left out the comment about the geological formations, so I added that into his quote for him

Tea time last Tuesday made me laugh out loud!

Very glad to hear that things have improved. Wonderful quote from Hutton. Thank you and take care.