Gertrude Bell and the Finsteraarhorn

Diplomat, spy, photographer, activist, archeologist: oh, and she also put up a few routes in the Alps. [2400 words, 10 mins

A woman is at the forefront of Alpine mountaineering for several years, including a couple of impressive first ascents. History, of course, ignores her achievements. We put this down to gender prejudice and the Patriarchy.

But in the case of Gertrude Bell, there’s a rather different reason. The stuff she did later in life is just so much more spectacular even than her climb on the Matterhorn and her Lauteraarhorn-Schreckhorn traverse. Even, than her epic two days on the Finsteraarhorn. Like, founding the 20th-century state of Iraq…

Gertrude Bell came from a family originally of Cumbrian sheep farmers, moving up through the generations to become successful and wealthy industrialists in coal and engineering. Her favourite uncle became British ambassador to Persia. A fiercely intelligent young woman, in 1886 she gained a place at Lady Margaret Hall at Oxford University. She cut a year off the three-year course, becoming the first woman to gain First Class Honours in Modern History. (At Oxford, in the 1880s, ‘Modern’ started with the fall of the Roman Empire.)

This didn’t, of course, make her into Miss G. Bell B.A. – it would be another 30 years before Oxford would award degrees to people without penises.

She filled the next 25 years with travel, archeology, a spot of mountaineering which we’ll come to in a moment, and anti-suffragette activism. Yes, she was against votes for women. In those late 1800s, only men with property could vote. Women, unless they were widows, could not hold property. She thought it more important to tackle those two inequities.

She travelled right around the world by steamship. Then she did it again. Acquiring six languages including Turkish, Arabic and Farsi. On her archeology journeys through the Near East she travelled 20,000 miles by horse and camel with no European companion of either sex.

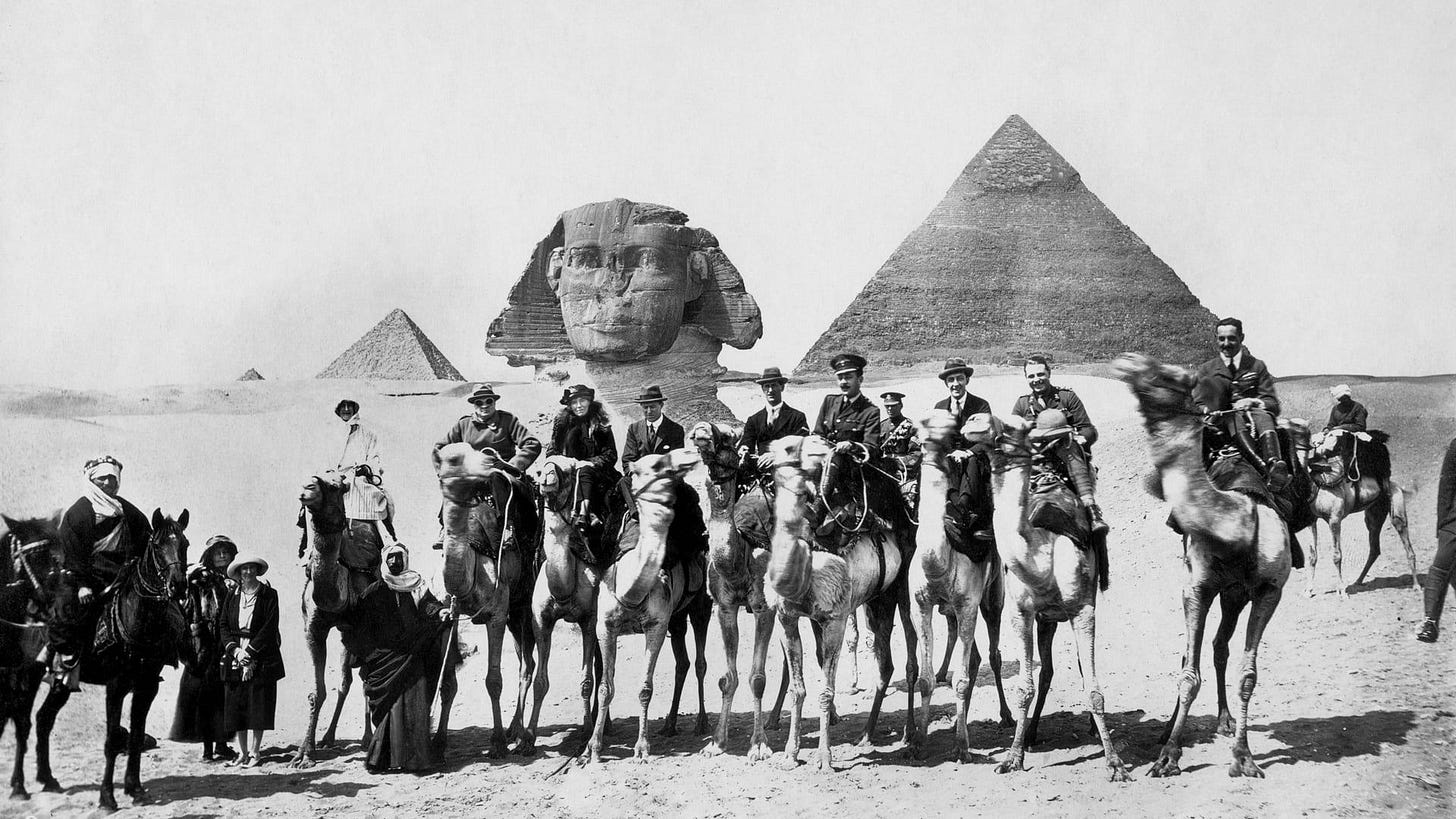

Such was her knowledge and competence that she was sent to Cairo in 1915 as the first ever woman officer in British Military Intelligence. Promoting Arab as well as British interests, she collaborated with TE Laurence of Arabia: “She is a remarkably clever woman … with the brains of a man.” A sheikh who negotiated with Bell is supposed to have commented, “if this is one of their women, what must their men be like?”

As a diplomat she’s considered responsible for setting up the Hashemite monarchy in Iraq: reasonably benevolent, effective, and only modestly corrupt, it continued until 1958 before being supplanted by Saddam Hussein.

But let’s leave aside the boring old politics and get ourselves up into the Alps. Because quite apart from the gadding about on camels and political shenanigans: the climbs, in themselves, are well worth looking over.

Gertrude Bell hit the Alps in 1899, around her 31st birthday. Starting as she meant to go on, with a 17 1/2 hour traverse of the Meije, in her underclothes as skirts were too cumbersome and she owned no trousers. But she got hold of some for her next climb, a 19 hour blizzard epic on the Barre des Écrins; her fingers got a bit frostbitten on that one, but never mind.

In 1900 she knocked off Mont Blanc and the Aiguille du Grépon, now in a bespoke blue climbing suit: the traverse of the Grand and Petit Dru gave another epic day. Rather than seeking out fellow climbers (the Alpine Club was closed to woman until 1974 anyway) she employed Swiss guides on her climbs. In 1901 she linked up with Ulrich and Heinrich Fuhrer,1 who would become her closest climbing colleagues.

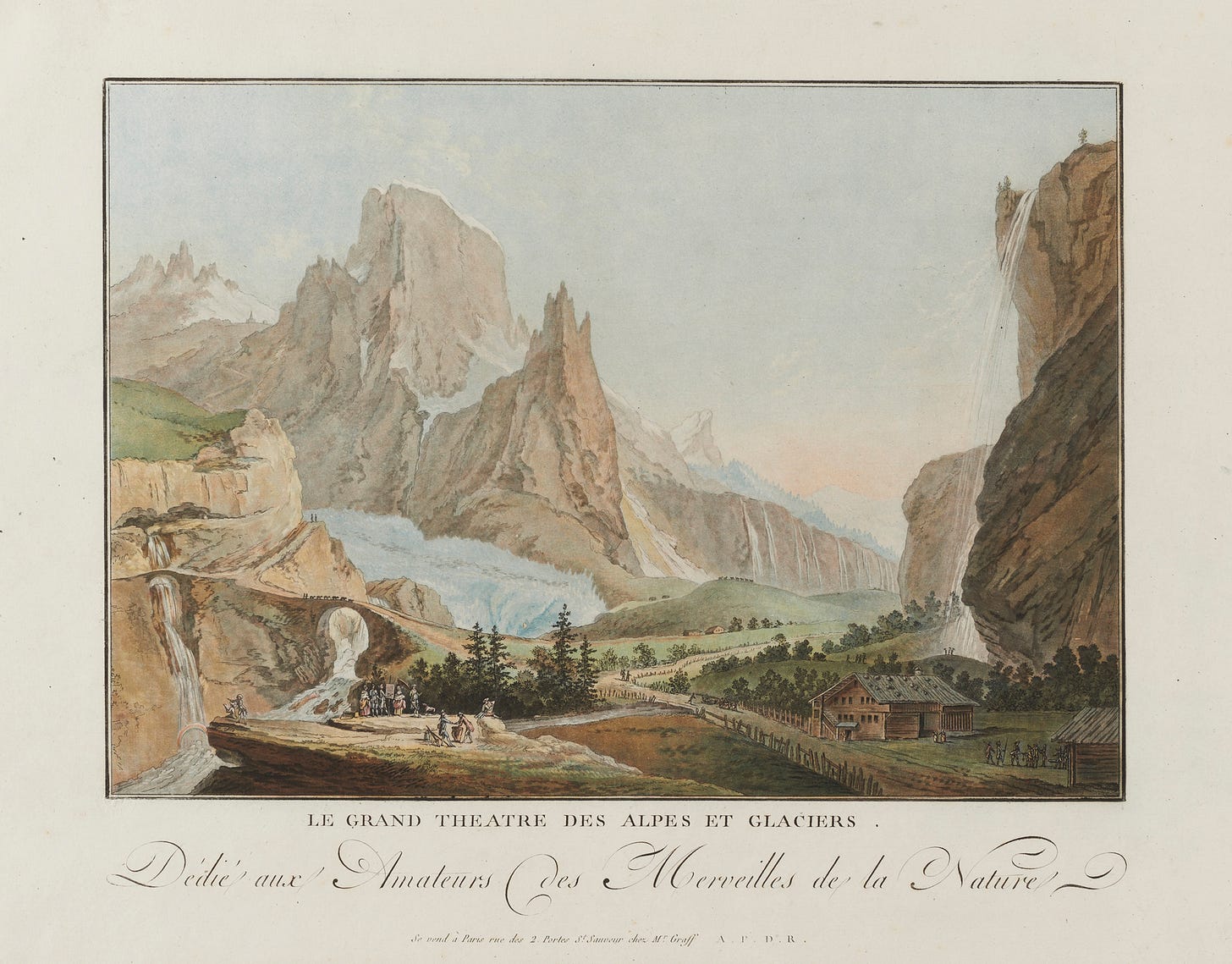

In 1901 – I’m trying to summarise here, as I want to get on to that epic on the Finsteraarhorn – but I already see my summarising isn’t going to be very successful. Anyway, the weather being bad, they put up ten new rock routes or unclimbed summits on the Engelhörner above Grindelwald. Using as required the dodgy échelle court or ‘human ladder’ technique:

Ulrich climbed up by the rock and our bodies and planted himself firmly on the back of my neck and I felt him fingering up for the hold above him. Presently he remarked, conversationally: “I do not feel very safe. If you move, we are all dead.”

Ulrich stated that they would never have completed the traverse without her climbing skills: “as good as any man”.

In 1902 they made the first crossing of the Lauteraarhorn-Schreckhorn traverse. No, not just the first female crossing, the first by any gender. But only just – coming off the mountain, they met a Fraulein Kuntze and her guides coming the other way.

In 1904 they would traverse the Matterhorn – up the Italian ridge and down the Zmutt – as well as visiting the Lyskamm and the various summits of Monte Rosa. After which she would concentrate on archaeology and founding modern Iraq. But, among all these successes there was also one spectacular failure.

The North-east Spur of the Finsteraarhorn was an extraordinary, futuristic, chapter in Alpine history. Two decades before the Schmidt brothers triumphed on the Matterhorn, before the Walker Spur attempts, before the Eiger and all those other great Nordwand dramas o f the thirties, the Finsteraarhorn wall had already been climbed. In the modern guidebook, the North-east Spur is graded ED: this 1902 attempt was one of the great Alpine epics of the last century.

Stephen Venables (abridged for shortness)2

And Gertrude Bell wrote it up, in detail, in a letter to her brother three days later. “I shall remember every inch of that rockface for the rest of my life.”

The arête rises from the glacier in a great series of gendarmes and towers, set at such an angle on the steep face of the mountain that you wonder how they can stand at all and indeed they can scarcely be said to stand, for the great points of them are continually over-balancing and tumbling down into the couloirs between the arêtes and they are all capped with loosely poised stones, jutting out and hanging over and ready to fall at any moment. But as long as you keep pretty near to the top of the arête you are safe from them.

… It was dangerous because the whole rock was so treacherous. I found this out very early in the morning by putting my hand into the crack of a rock which looked as if it went into the very foundations of things. About 2 feet square of rock tumbled out upon me and knocked me a little way down the hill till I managed to part company with it on a tiny ledge. I got back on to my feet without being pulled up by the rope, which was as well for a little later I happened to pass the rope through my hands and found that it had been cut half through about a yard from my waist when the rock had fallen on it. This was rather a nuisance as it shortened a rope we often wanted long to allow of our going up difficult chimneys in turn. So on and on we went up the arête and the towers multiplied like rabbits above and grew steeper and steeper and about 2 o’clock I looked round and saw great black clouds rolling up from the west.

At three o’ clock they were about 700m up the 1000m spur, though still below the Grey Tower which is now known to be the hardest part. But the weather was closing in, and now the first snow began to fall. Despite the difficulty of what they had already climbed, it was time to turn back.

By 8pm, snow covered the rocks and a blizzard was raging.

We were standing by a great upright on the top of a tower when suddenly it gave a crack and a blue flame sat on it for a second, just like the one we saw when we were driving, you remember, only nearer. My ice axe jumped in my hand and I thought the steel felt hot through my woollen glove—was that possible ? I didn’t take my glove off to see. Before we knew where we were the rock flashed again—it was a great sticking out stone and I expect it attracted the lightning, but we didn’t stop to consider this theory but tumbled down a chimney as hard as ever we could, one on top of the other, buried our ice axe heads in some shale at the bottom of it and hurriedly retreated from them. It’s not nice to carry a private lightning conductor in your hand in the thick of a thunderstorm.

They found a place to bivouac, half-sheltered in a small crack in the rocks.

At first the thunderstorm made things rather exciting. The claps followed the flashes so close that there seemed no interval between them. We tied ourselves firmly on to the rock above lest as Ulrich philosophically said one of us should be struck and fall out. The rocks were all crackling round us and fizzing like damp wood which is just beginning to burn—have you ever heard that ? It’s a curious exciting sound rather exhilarating—and as there was no further precaution possible I enjoyed the extraordinary magnificence of the storm with a free mind : it was worth seeing.

In the morning the blizzard had blown out. But they were in thick mist, and the rocks completely covered over in new snow.

Both the ropes were thoroughly iced and terribly difficult to manage,3 and the weather was appalling. It snowed all day sometimes softly as decent snow should fall, sometimes driven by a furious bitter wind which enveloped us not only in the falling snow, but lifted all the light powdery snow from the rocks and sent it whirling down the precipices and into the couloirs and on to us indifferently. It was rather interesting to see the way a mountain behaves in a snowstorm and how avalanches are born and all the wonderful and terrible things that happen in high places. The couloirs were all running with snow rivers—we had to cross one and a nasty uncomfortable process it was. As soon as you cut a step it was filled up before you could put your foot into it. But I think that when things are as bad as ever they can be you cease to mind them much. You set your teeth and battle with the fates ; we meant to get down whatever happened and it was such an exciting business that we had no time to think of the discomfort.

Through the whole day they climbed downwards, reaching the glacier at 8pm, in the dark and soaked through. Unfortunately their matches were also wet; even improvising a dry tent under her skirt, they were unable to light them. And so, without the use of their lantern, they had to bivouac for a second night, on the open glacier in the rain, sitting on iceaxes with their feet in the rucksacks.

Isn’t that an awful dreadful adventure ! It makes me laugh to think of it, but seriously now that I am comfortably indoors, I do rather wonder that we ever got down the Finsteraarhorn and that we were not frozen at the bottom of it. What do you think?

Writing in the National Review after the Engelhörner climbs, Bell fills us in on her attitude to climbing – and, perhaps, to life as a whole.

Of all perverse passions, that of the mountaineer is one of the most inexplicable. … we who leave our beds to lie upon straw, our ease for days of unrewarded toil, and exchange our well-appointed meals for a dry prune and a drier crust, what sense is there in our folly ? Let me at once disarm criticism : there is none, or at least there is none which would appeal to a judge were he not predisposed in favour of the defendant. For which reason the self-respecting mountaineer makes occasion from time to time to slip a persuasive word into such ears as will hear, sometimes taking cover under the much mishandled robe of science, sometimes masquerading as the observer of men and manners under strange conditions, sometimes as the artist, discoursing of colour values, of purple and of orange on the snows. ' See now ! ' he says, ' we, too, take an interest in matters appertaining to the reason and the imagination ; we are neither fools nor mad : such and such things we seek in the hills, as your Honour seeks them in other places, but it is the same search.' And all the time he hugs to his heart some memory of the last labouring step up the long ice slope, of the desperate reaching out into the void round an overhanging rock corner—moments when the brain throbs with an almost uncontrollable excitement and a glowing ardour which would ennoble any pursuit for him who had felt it.

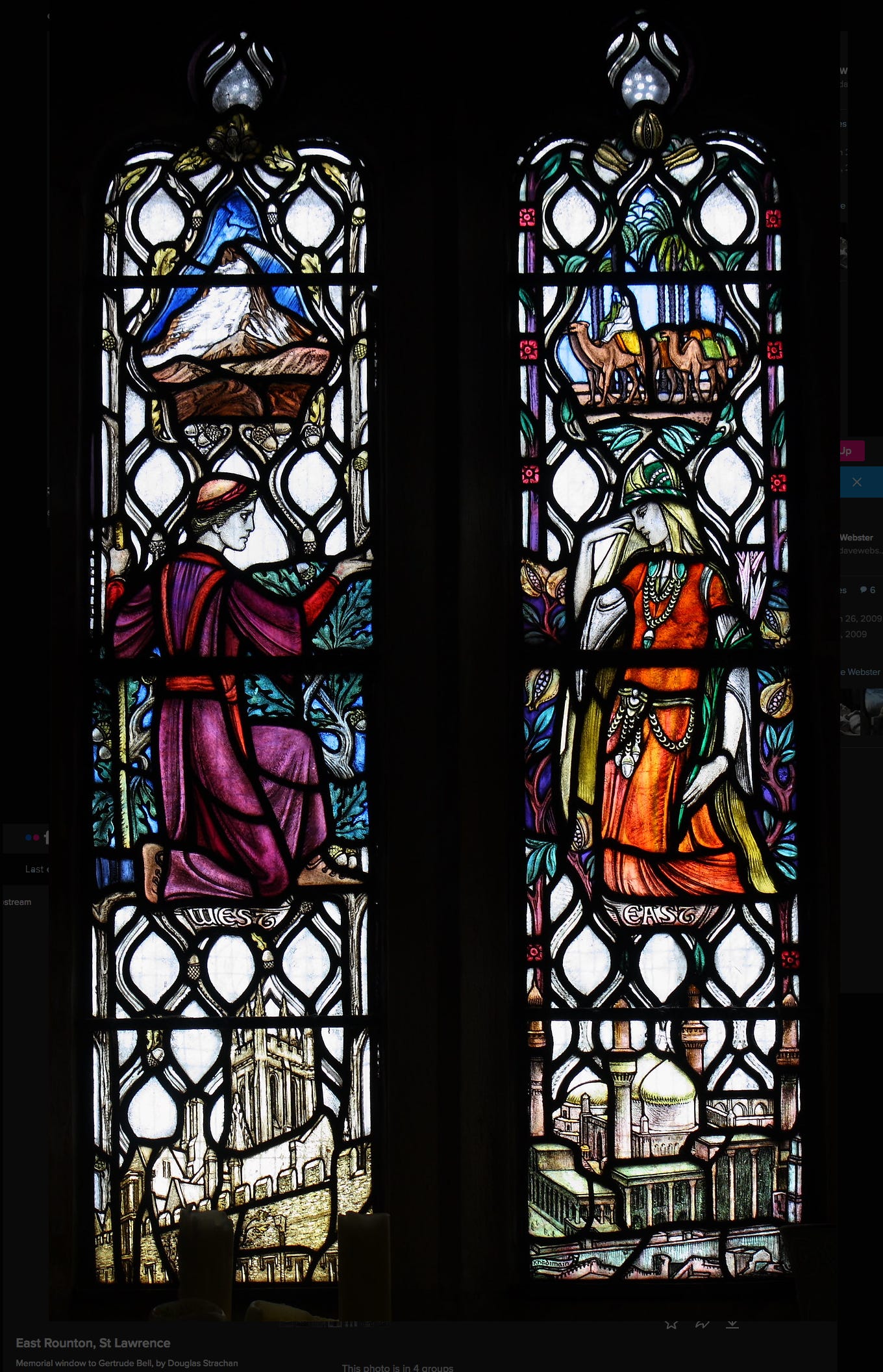

Her work done in this world, at the age of 57 Gertrude Bell died by suicide with sleeping pills. The Baghdad Museum that she founded was looted during the second Gulf War, and largely destroyed.

She does, though, live on in Werner Herzog's 2015 film Queen of the Desert. With one of Herzog’s worst-ever screenplays, it stars Nicole Kidman along with James Franco, plus Robert Pattinson as Laurence of Arabia. “As stunningly picturesque as all of this undeniably proves to be, Queen of the Desert is a barren emotional quagmire, Bell's incredible story deserving of so much more than this movie sadly proves to be willing to offer.”4

The Finsteraarhorn, disappointingly, doesn’t feature. But you can watch it anyway if you want to: the full film’s on YouTube. Here’s the trailer.

What looks to be a whole lot better (apart from still not featuring the Finsteraarhorn) is the documentary Letters from Baghdad, directed by Sabine Krayenbühl and Zeva Oelbaum (2017) and with the voice of Tilda Swinton. “The documentary she deserves,” says The Guardian. The film is currently on various platforms including free to subscribers on Amazon Prime.

Meanwhile, her full 4000-word account of the Finsteraarhorn can be found in her Collected Letters Vol 1 (August 1902).

Yes, her guide was called Mr Guide.

Venables, Alpine Journal 2004 p176 ‘Finsteraarhorn NE Spur Centenary’

Hemp ropes of the time, maybe around 2.5cm diameter, absorbed water freely and when wet became stiff and heavy. If the temperature dropped they could then freeze rigid.

Sara Michelle Fetters, top critic on Rotten Tomatoes

Epic stuff, have already read her Mid East escapades. Didn’t know she was a mountaineer as well. Quite a lady!