Enid Blyton hikes

I was going to post about Coleridge again. But then I stopped at my local café for a haggis-and-cheese toastie. [1000 words, 4 mins

A sunny November day, so I switch off my computer and take a walk. Down the wide river that defines the valley where I live, a pause – you can’t pass without pausing – at the three-way waters where the big tributary comes in from the hills to the west. Up the tributary river, and this is gratifying: 12 months ago, this was blocked by brambles and I came along with my secateurs and opened it up. And now, at the end of another summer, people have been using it, some of them possibly with secateurs of their own; an hour’s work from me and the path’s stayed open all year and maybe next year and the year after as well.

At the top of the tributary, a little sandstone village with windfarm money, and they’ve spent their windfarm windfall on a community café. Not just a café either, but also a bookshop – along the lines of bring a book, take a book, and put a pound coin in the collection box. And so, over my haggis toastie (I don’t wear the kilt, my Gaelic is hill names only, but I do like my haggis toastie) – but what is this on the book-buy shelf today.

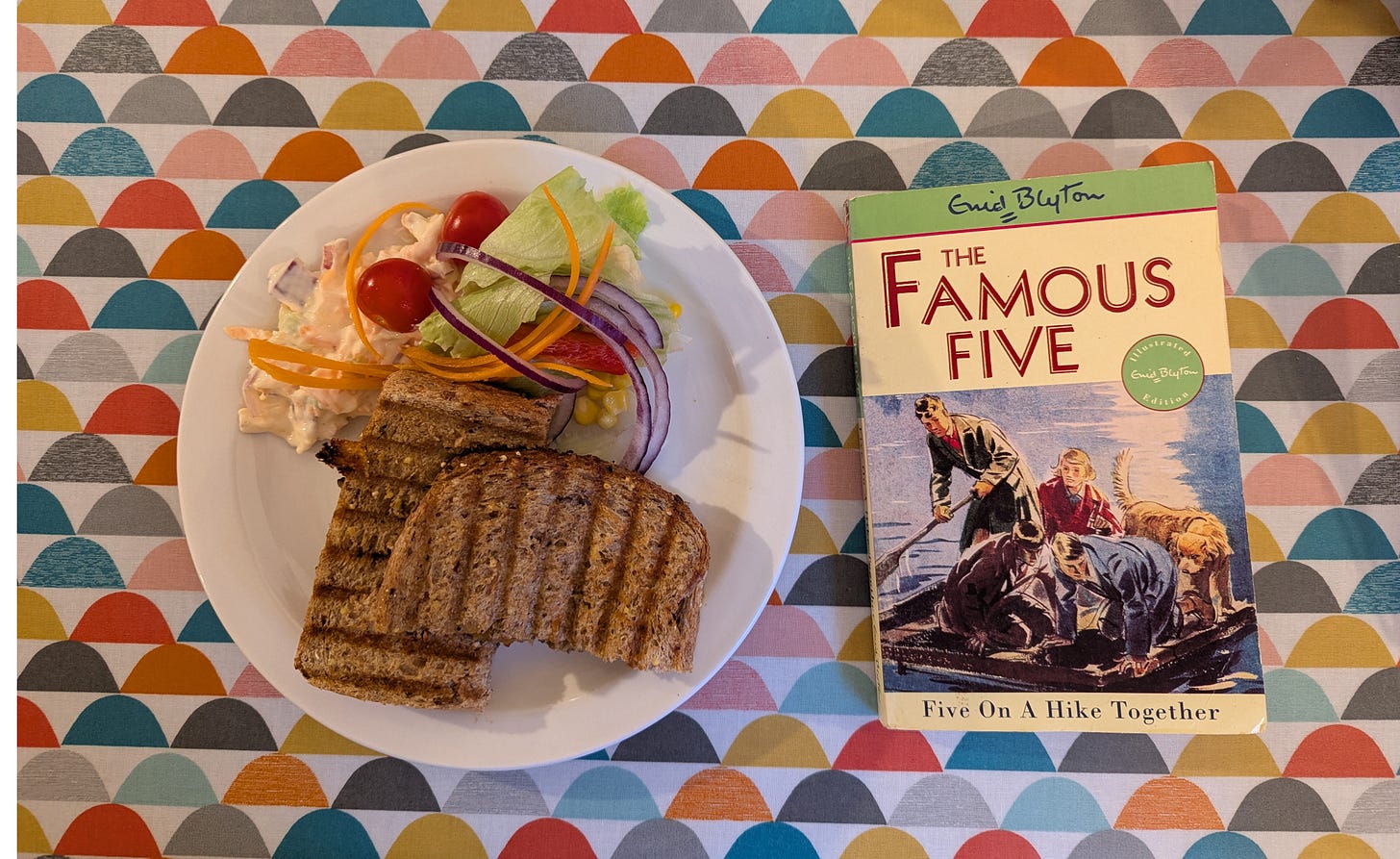

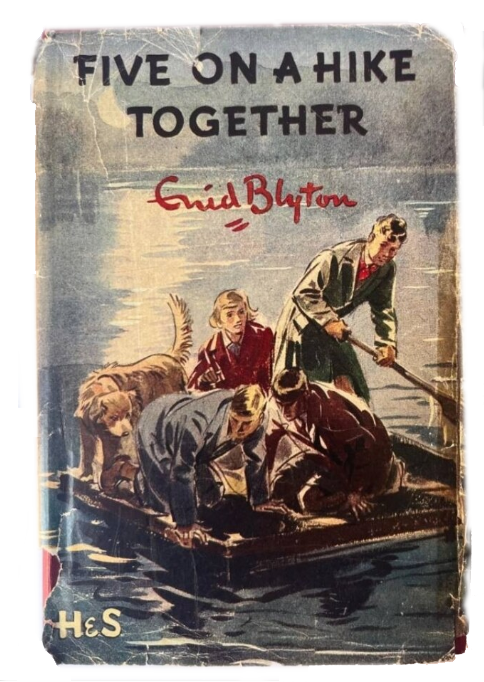

It’s Enid Blyton. Five Go For a Hike.

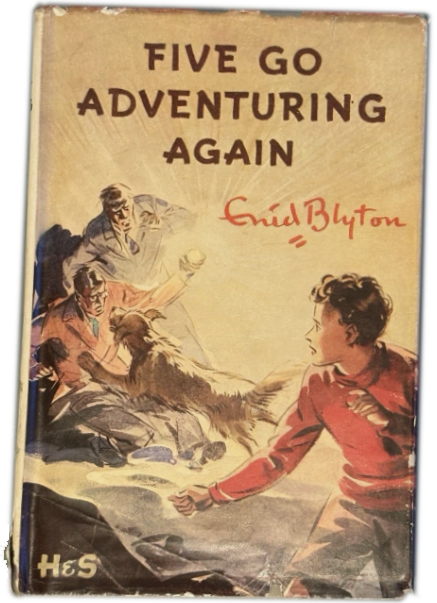

The first book I ever read all by myself, all the way through: it was Five Go Adventuring Again. Julian, Dick, George (who’s a girl), Anne, and Timmy the dog. And I have to say that it’s stayed with me. The sinister gypsies. The whopping big picnics. The hidden coves with their underground passages leading inland to emerge through a secret panel into the sinister mansion, which has a tower and a kidnapped child and two swarthy villains who, oh infamy, had gone so far as to administer doped meat to Timmy the dog!1

And now here they are again, going for a hike.

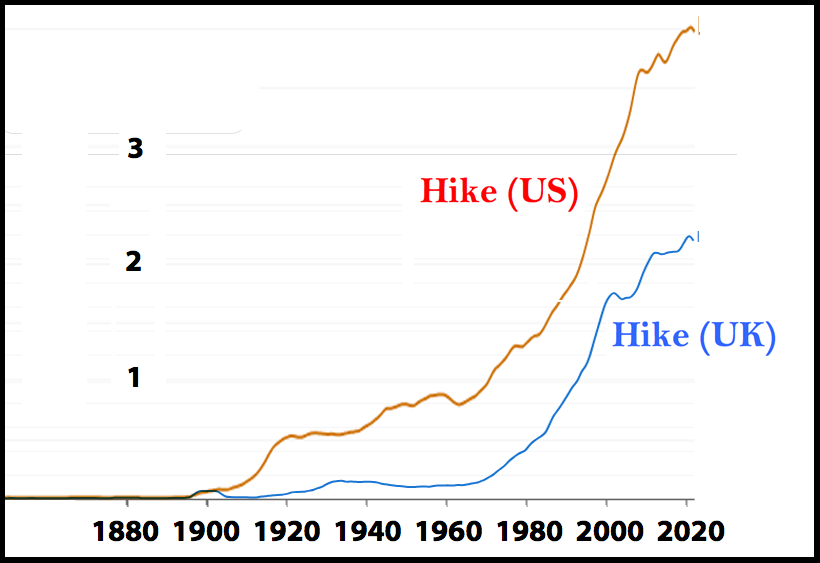

A ‘hike’? Yes, that word was current here in the UK, back then in the 1930s. Imported from America, but in use by those energetic types in shorts, opening up their one-inch maps as they calculate the fifteen or twenty miles to the next youth hostel.

By the end of my toastie, I’m already three chapters in. Though not named as such, it’s got to be Dartmoor. A four-day circuit, with planned overnights in country inns and random farmhouses, none of them pre-booked.

In the years between, I don’t think I’ve read another Blyton. ‘Adventuring Again’ may even have been a mistake: my Mother hadn’t realised how strongly Enid Blyton was disparaged in any smart middle-class family. (Today Blyton stories are criticised for their sexism, class prejudice, and racism against gypsies. But back then it was more to do with the absence of even traces of literary merit.)2

Blyton herself was a remarkable woman. The most prolific author in English is supposed to be L Ron Hubbard, the science-fiction writer who invented Scientology. L Ron is credited with 1084 unique books. But Blyton – what with Noddy & Big Ears, and Mallory Towers, and the Secret Seven, and the Famous Five – she also wrote plays and rhymes and educational primers. And if you count in her compilations of short stories; well, the Blyton Society credits her with (depending on what counts as a book) 2164 separate and distinct stories. She typed fast, and she didn’t revise, and she could write a full length Famous Five or Secret Seven in a week. Once, when she wanted the weekend free to play golf, she wrote a Famous Five in five days.3

And – well – maybe she wasn’t a hiker. But she was a walker. With her husband Kenneth Waters, who was also her financial manager, she holidayed three times a year on Dorset’s Jurassic Coast. Kirrin Castle is based on Corfe; the secret coves, though they feel to me like Cornwall, are taken from Kimmeridge Bay and Swanage. Studland village itself has the embarrassing distinction of being the original of Toytown, in the ‘Noddy’ series for tiniest readers.

‘Five Go For a Hike’ – it’s not one of the five-day ones, but I can believe it was written in a week. The characterisation is thin: perhaps the most well rounded being Timmy the dog, as he has not one, not two but three characteristics: likes to lick people, is interested in rabbits, and goes ‘woof’. George the girl who regenders her name (at school she’s Georgina) and claims the freedom and responsibility accorded to boys: intriguing, is this perhaps an early example of Queer Literature? Well, being George not Georgina is George’s single selling point, and I’m sorry to say when it’s time to prepare the whopping picnic and do the washing up she steps forward in traditional girl-guide style.

But yes, this hiking book has been written by a walker. The somewhat smug Julian, who always knows what to do: he splits the party, sending Anne and Dick (the two youngest) to find their own way towards Blue Pond Farm, with two hours left of daylight and no map. And they get into one of those sunken lanes, the ones with mud in the bottom and as you get downhill the mud turns to a small stream. High in the hedge there’s a break against the sky, and a stile, and a path which leads across two open fields and then a gate onto the pathless heathery moor.

I think we’ve all been there.

So, is it a good read? Well, it’s all jolly exciting, and now and then there’s a nice bit of landscape as well, moonlight on the lonely lake sort of thing. And it has all been updated in a sensitive way for the present day: wherever Julian would have tipped the friendly shopkeeper a shilling (a whopping fruit-cake added into the sandwich order), the shilling’s been modernised into 5p (about 8 cents, for Europeans or Americans). Making Julian seem not only smug but also grotesquely stingy. But the hike, sadly, is rather short. One day in they bump into a pair of scowly working-class types with obviously evil intentions and a mysterious map. And, sadly, that’s the end of their four-day circuit of Dartmoor.

Now I just need to hunt down ‘The Mountain of Adventure’. Google says it’s got wolves in…

Actually, my memory’s not quite that good. I checked ‘Adventuring Again’ out of the library a few years back to confirm the main plot points. I was writing about the Lake District’s ‘coves’ which are what’s elsewhere called corries, but are almost as remote and romantic as proper Famous Five ones.

From the early 1960s Blyton was also being widely banned from libraries. This may be because there wasn’t shelf space to stock the hundreds of titles; in order to be selective librarians were obliged to read the things, and they simply found this to be unbearable.)

Note that I did say most prolific in English. The Spanish author Maria del Socorro Tellado López, the most read Spanish author after Miguel Cervantes, published over 4000 titles in the ‘pink prose’ (novela rosa) romantic fiction genre.

There was always adventure in an Enid Blyton book, and goodies and baddies, and I loved them all as a child. I'd spend my pocket money and fill a shelf in my.bedroom bookcase. Enid Blyton helped me develop a hunger for reading. We might not recommend these books today, but back then I couldn't get enough.

Thank for the memories Ronald!

Also, for what it's worth, I absolutely loved Enid Blyton when I was growing up (especially the Adventure series) but my children don't like them at all, and when I tried to read her books to my kids, I quickly realised how awful they were (the books not the children). It was possibly a mistake to start with Mr Pinkwhistle. However, she's not entirely out of fashion - there's a film of the Magic Faraway Tree coming out soon. Another great children's author who probably deserved to be more popular was Malcolm Saville.