Coleridge's trip to 'Sham-onix'

The 19th century craze for people writing poems about Mont Blanc (even if they'd never been there) [1700 words 7 mins

The German-speaking Danish poet Friedericke Brun: it was her who started it, back in 1791.

Chamonix beym Sonnenaufgange (Chamonix at Sunrise)

From the deep shadow of the silent fir-grove

I lift my eyes, and trembling look on thee,

Brow of eternity, thou dazzling peak,

From whose calm height my dreaming spirit mounts

And soars away into the infinite!

[translation uncredited, possibly Jason M Kelly]

Friederike Brun, painted by CW Eckersberg

Eleven years after that, on Thursday 5th August 1802, the poet Coleridge made his ill-judged scrambling descent of Broad Stand on Sca Fell.

I shook all over, Heaven knows without the least influence of Fear / and now I had only two more to drop down / to return was impossible – but of these two the first was tremendous / it was twice my own height, & the Ledge at the bottom was [so] exceedingly narrow, that if I dropt down upon it I must of necessity have fallen backwards & of course killed myself... I lay in a state of almost prophetic Trance & Delight – & blessed God aloud….1

Scafell: Coleridge’s ill-judged descent route arrowed

Coleridge realised there was poetry to be plucked from this near-death adventure, given that he’d already got it down in incandescent prose. But for some reason believed that Sca Fell was too small. So he shifted it to a hill he'd never even seen, let alone been on, translating (unacknowledged) and adapting Friedericke Brun’s original.2

Hymn Before Sun-Rise, in the Vale of Chamouni

Deep is the sky, and black: transpicuous, deep,

An ebon mass!But when I look again,

It seems thy own calm home, thy crystal shrine,

Thy habitation from eternity. […]Entranc’d in pray’r,

I worshipp’d the INVISIBLE alone.

Yet thou, meantime, wast working on my soul,

E’en like some deep enchanting melody,

So sweet, we know not, we are list’ning to it.Awake, awake! and thou, my heart, awake!

Awake ye rocks! Ye forest pines, awake!

Green fields, and icy cliffs! All join my hymn!

If you really want it, the full poem is here.

The trouble was: Coleridge never climbed Mont Blanc. Worse than that, he never even saw the thing. He betrayed his own experience on Sca Fell (5th August 1802, remember?) and incorporated Friederika’s moral: “the signs and wonders … utter forth God.”

Coleridge was a Unitarian, the most irreligious form of religion available in the 1790s. He knows that whatever we see when we look at Mont Blanc, it's not God. But he also suspects that's what the punters want. A bit like Liz Truss's tax cuts.3

But the one big merit of Coleridge's Mont Blanc poem is: firing up various future poets to write it again, and write it right. Because it does seem like STC, with a bit of friendly help from Friederike, started a fashion for writing up the high point of the Alps.

Mont Blanc rhymer no. 3: Byron

George Gordon Lord Byron too was a fair fellwalker. He went up Lochnagar by a seriously rocky route – the hill’s first recorded ascent, in fact. But having to flee England in disgrace in 1816 did give him the chance to get to know the Alps, and point his pen at the big one above Chamonix.

Byron's suspiciously byronlike antihero Manfred wants the seven spirits of the Romantic Outdoors to absolve him, or at least to wipe from his fevered memory, some dreadful (so dreadful he's not going to tell us what it was) offence involving someone called Astarte.

Spirit No. 2 is the big hill.

Mont Blanc is the monarch of mountains

They crowned him long ago

On a throne of rocks, in a robe of clouds,

With a diadem of snow.

Around his waist are forests braced,

The Avalanche in his hand;

But ere it fall, that thundering ball

Must pause for my command.

The Glacier's cold and restless mass

Moves onward day by day;

But I am he who bids it pass,

Or with its ice delay.

Manfred tries to do himself in by leaping off the Jungfrau in a pair of pointy shoes, but gets rescued by a passing chamois hunter. (Ford Madox Brown)

Matthew Arnold

Next to have a go at capturing France's (and Italy's) highest mountain in suitable stanzas is another Lake District fellwalker, mid-Victorian Matthew Arnold.

Not Mont Blanc as such, but from his extended ‘Switzerland’ sequence:

Ye are bound for the mountains!

With you let me go

Where your cold, distant barrier,

The vast range of snow,

Through the loose clouds lifts dimly

Its white peaks in air—

How deep is their stillness!

Ah, would I were there!

A Parting 1852

Hmmm – Mont Blanc 1, mid-Victorian Matthew 0. Let's move on.

Matthew Arnold: an avalanche of side-whiskers

John Ruskin

In ‘Evening at Chamouni’, the young author recreates Balmat's first ascent of Mont Blanc from 1786, while re-enacting the classic rückenfigur or romantical back view from Caspar David Friedrich’s ‘Wanderer above the Sea of Clouds’:

He stood alone amid the storm;

Watching the last day-gleams decay,

Supposing its returning ray

Should see him lying there asleep,

With Alpine snow for winding-sheet,

Methinks I see him, as he stood

Upon the ridge of snow;

The battering burst of winds above, –

The cloudy precipice below,

– Watching the dawn.

Ruskin was the leading landscape-appreciator of the mid-Victorian time. And the leading landscape-painting-appreciator as well, the one who persuaded the world to look seriously at the work of JMW Turner. But, as a poet, he was perhaps better as a painter… His watercolour of Mont Blanc captures the romantic view of it, huge and half-hidden by clouds.

Ruskin's painting of Mont Blanc: a truer view than any photograph and all but one of the poems

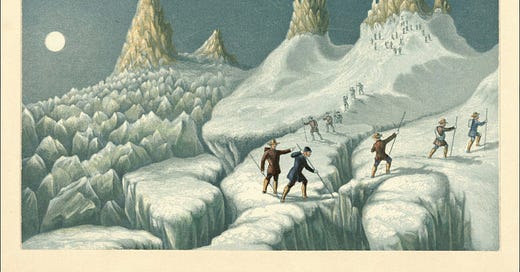

We’re forced to the conclusion that the best mountain poet is going to be the one who’s actually climbed the thing. Well, obviously. The poetical fellow who went up it the proper way, the steep path through the pine wood, overnight at the Grands Mountets, and then the passage of the ‘Ancien Corridor’ slantwise under the ice-towers just a few years before that historic route became so dangerous nobody did it any more…

Under the bridge at Chamonix:

The Arve, grey-watered from perpetual snow

Moving up into the pine forest above it:

Hot, scented and resinous like the hold of a spice-bearing galleon

And, happily for posterity, the rest of my Mont Blanc poem that I wrote back in 1972 has faded from my memory. Leaving just enough of it to clearly disprove the suggestion that actually going up Mont Blanc will make for more vibrant verses…

Is my clouded photo of Mont Blanc any better than my poem?

Because, of course, I've left out the one that really matters. Back in 1816, even as Lord Byron was rhyming his way through the avalanches and ice-towers within the mind of his metaphorical Manfred, Percy and Mary Shelley were hiking the mountain track above the gorges of the Arve.

Mont Blanc: Lines written in the Vale of Chamouni

We have to assume that Matthew Arnold and John Ruskin weren’t aware of Shelley's poem about the mountain – I know I wasn't, anyway. Because, where Mont Blanc’s concerned, this is the one that matters. From the river at its foot:

Thou many-colour'd, many-voiced vale,

Over whose pines, and crags, and caverns sail

Fast cloud-shadows and sunbeams: awful scene,

Where Power in likeness of the Arve comes down

From the ice-gulfs that gird his secret throne,

Bursting through these dark mountains like the flame

Of lightning through the tempest;

Before moving up onto the mountain itself: to the sudden, short glimpse of it among the clouds. The silent summit, where

… the flakes burn in the setting sun,

Or the star-beams dart through them.

And of course, I should have been going on about Shelley all along – except that I already did, in a 1500-word piece on the UKclimbing website. The poem itself is here; my account of it is here.

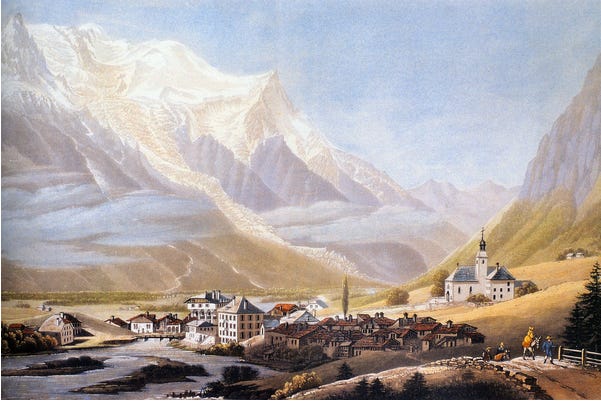

Chamonix valley and Mont Blanc as seen in 1810 (painter unknown)

Mont Blanc is hard going – but worth it, of course it's worth it, one of the great high places of the world. And just the same is true of ‘Mont Blanc’, Shelley's long poem. A poem which, I suspect, only exists because he read Coleridge’s one and went this is good, it’s so good. But oh, it could be so much better – and what’s all that God nonsense doing in there?

Because Shelley was a serious-minded atheist. Being a person looking at Mont Blanc has to involve Mont Blanc not being a metaphor for any theological entity.

Coleridge’s special moment on Broad Stand gets quoted quite often. So here’s the next stage of his walk, down into Upper Eskdale in a thunderstorm. Written down in a warm farmhouse the same evening, for conversion into some future poem, preferably not one about Mont Blanc. A poem that, in the end, didn’t get written. (Unless, perhaps, by Percy Shelley.)

But, honestly, why convert it into anything else? When you have writing like this:

I descended this low Hill which was all hollow beneath me – and was like the rough green Quilt of a Bed of waters – at length two streams burst out and took their way down, one on [one] side a high Ground upon this Ridge, the other on the other – I took that to my right (having on my left this high Ground, and the other Stream, and beyond that Doe-crag, on the other side of which is Esk Halse, where the head-spring of the Esk rises, and running down the Hill and in upon the Vale looks and actually deceived me, as a great Turnpike Road – in which, as in many other respects the Head of Eskdale much resembles Langdale) and soon the channel sank all at once, at least 40 yards, and formed a magnificent Waterfall – and close under this a succession of Waterfalls 7 in number, the third of which is nearly as high as the first.4

Upper Eskdale, seen from my bivvy bag

From his letter written the same evening to Sara Hutchinson. The full text of his 9-day walking tour is at Lancaster University. The descent of Sca Fell is at Day 5.

"I involuntarily poured forth a Hymn in the manner of the Psalms, tho' afterwards I thought the Ideas &c disproportionate to our humble mountains—& accidentally lighting on a short Note in some swiss Poems, concerning the Vale of Chamouny, & it's Mountain, I transferred myself thither, in the Spirit, & adapted my former feelings to these grander external objects."

This may be a faulty comparison. The evidence suggests Liz Truss did actually believe in those unfunded tax cuts she cooked up with Kwasi Kwarteng in October 2022.

Punctuation slighty tidied. ‘Doe-crag’ refers to Scafell Pike, Dow Crag being the OS-recorded name for what climbers now call Esk Buttress. The waterfalls are Cam Spout.

I was just researching Mont Blanc myself was very interested to learn that the first woman who climbed it was a maid who (rightly, it seems) figured that making it to the top of the mountain might elevate her status enough to change her life. She doesn't get credit for being the first female mountaineer, though, because she wasn't climbing for the 'right' reasons. Really enjoyed this read, and especially the illustrations!

Another excellent read.

Next stop the Bernese Oberland? It influenced both Arthur Conan Doyle and JRR Tolkien, to name but two.