Charles Dickens climbs Carrock Fell

Carrock being a 2174ft high hill in the Lake District. Meanwhile Wilkie Collins is doing all he can to keep up ... [1200 words 5 mins

At the end of August 1857, Charles Dickens and his novel-writing pal Wilkie Collins set out from London for a walking tour of the North Country. They didn’t get far. Just five miles up the Great North Road, they thought better of it and turned back to Euston Station to take the train. As Wilkie Collins put it: “What was the use of walking, when you could ride at such a pace as that? Was it to see the country? If that was the object, look out of the carriage window. There was a great deal more of it to be seen there than here. Besides, who wanted to see the country? Nobody.”

Dickens’s friend, colleague and occasional collaborator Wilkie Collins was the leading horror-story writer of the Victorian era.1 The Woman in White and The Moonstone are both good creepy reads.

Poor Wilkie may have been a bit of a wimp: but Charles Dickens was a serious long-distance walker. Sometimes just as a way of getting from A to B with a bit of vigorous exercise along the way: “straight on end to a definite goal at a round place” – such as an overnight hike from his London home near Euston Station to his Kent one at Gad’s Hill near Rochester: 30 miles by today’s direct road route off Google Maps. With a 2am start, he finished that one in time for breakfast – he reckoned on a walking speed of 4mph.2 That speed and distance would be considered ‘power walking’ nowadays – or ‘pedestrianism’ in the appropriate Victorian term.

”If I could not walk far and fast, I think I should just explode and perish.”

Charles Dickens

So Dickens was a serious walker.3

Wilkie Collins, sadly, not so much …

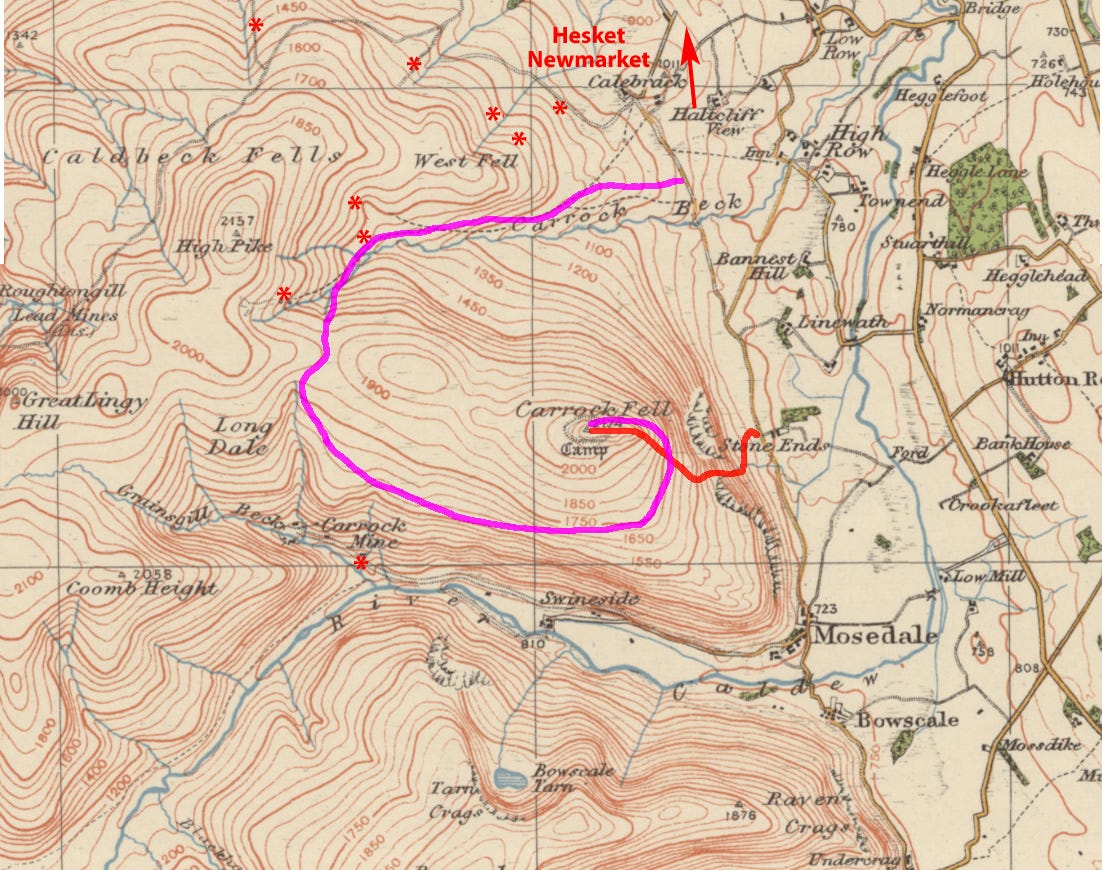

From Carlisle station, they rode to Hesket Newmarket, in quest of “a certain black old Cumberland hill or mountain, called Carrock, or Carrock Fell”. Why Carrock? They were almost certainly unaware that the poet Coleridge had sat out a thunderstorm on its summit 57 years before.4 Carrock stands at the north-east corner of the Lake District, at the edge of the ‘Back o’ Skiddaw’ group, and may have been chosen simply as the closest to Carlisle. The point being, to write it all up for their jointly-published magazine ‘Household Words’.

They stopped off at the Old Crown, whose innkeeper offered to serve them as mountain guide. (The Old Crown is now a community-owned pub with its own micro-brewery and is very welcoming to walkers.) Here they took a snack of oatcakes and whisky.

They then travelled by dog cart to a ‘lonely farmhouse’. My guess is that this would be Stone Ends, down to east of the summit. This is where I started my most recent ascent of Carrock Fell, with an old peat-cutters’ path heading up onto the southeast spur; and the subsequent geography fits with Wilkie Collins’s description.5

The sides looked steep, and the top was lost in the mist, and it was raining. Dickens was all up for it. Wilkie Collins wasn’t, but went along anyway. The innkeeper seemed cheerful enough.

Through rocks and bogs, over innumerable false summits, and up into the mist: Wilkie Collins trailing all the way, with his boots filled up with water, and his sodden overcoat sticking out sideways like a candle-snuffer.

The wind, a wind unknown in the happy valley, blows keen and strong; the rain-mist gets impenetrable; a dreary little cairn of stones appears. [Wilkie Collins], drenched and panting, stands up with his back to the wind, ascertains distinctly that this is the top at last, looks round with all the little curiosity that is left in him, and gets, in return, a magnificent view of – Nothing!

The Lazy Tour of Two Idle Apprentices by Wilkie Collins and Charles Dickens, the Carrock chapter being by Wilkie C.

“And now it becomes imperatively necessary to settle the exact situation of the farm-house in the valley at which the dog-cart has been left.” Fortunately, Dickens is equipped. He has a compass!

No map: a copy of Jonathan Otley's one of 1818 would have been a help here, but no, Dickens hasn't got it. Still, at least the compass will let them settle the correct direction to get back to the lonely farmhouse and their dog-cart.

Unfortunately, the straight-line bearing would take them over a “frightful chasm, called the Black Arches”. Avoiding this means they must contour sideways around the slope. And keep on contouring, to the disgust of the wet and weary Wilkie Collins. “Where men want to get to the bottom of a mountain, their business is to walk down it; and he put this view of the case, not only with emphasis, but even with some asperity.”

But the compass says, keep contouring. Just to make sure, Dickens puts it down on a rock for the needle to steady. The compass falls off the rock, the glass front falls off the compass; the compass needle falls out into the heather, and that’s it with the compass.

After another quarter-hour of contouring, they reach a stream in a small ravine. After some discussion, they decide to stop contouring and follow the little ravine downhill, crossing and recrossing the stream as required.

While recrossing the stream for perhaps the seventh time, Wilkie Collins slips on a wet stone and wrenches his ankle. Badly. He hobbles downhill, supported by Dickens and the landlord, until at last they come across one of the abandoned mines on the north side of the hill6. Now on gentler slopes they at last drop out of the mist, and find the moorland road not too far below.

Glad we found our way off okay, says the innkeeper. The last chap who got benighted up there, he was still alive the next morning but dead soon enough after that.

The innkeeper heads down the road to retrieve the dog-cart: under the low cloud and heavy rain, the landscape is reminding the miserable Wilkie Collins of “some enormous jorum of antedeluvian toast-and-water. The vast curtains of mist and cloud passed before the shadowy forms of the hills, streamed water as they were drawn across the landscape.”

Because, as any walking author knows, it's the miserable, injured, rain-sodden days that make the best write-ups. Back at the inn, out of their wet clothes and some whisky into them, and off they went to Wigton.

With Wilkie Collins laid up, there’d be no more walking on their north-country walking tour. They fill out their account with a couple of ghost stories instead.

Okay, maybe Bram Stoker (Dracula, 1894) is his rival for that title.

In ‘The Uncommercial Traveller’ (Chapter X) Dickens also describes his ‘objectless, loitering and purely vagabond’ style of rambling around London, absorbing material for his novels; there’s a long London night-walk in ‘Our Mutual Friend’. A short survey of Dickens’ long walks is on Luke McKernan’s website.

“Explode and perish” - Dickens must have posted this on his blog as it’s all over the Internet but with no source ever cited.

“A thick cloud came on, and wrapped me in such Darkness that I could not see ten yards before me ... I descended by the side of a torrent, and passed, or rather crawled (for I was forced to descend on all fours), by many a naked waterfall, till, fatigued and hungry (and with a finger almost broken, and which [writing the letter 7 days later] remains swelled to the size of two fingers), I reached the narrow vale.” Coleridge, letter to Humphrey Davy October 1800.

‘The Lazy Tour of Two Idle Apprentices’ is online here .

I’m assuming ‘north side of the hill’, as that’s where the former mines are - apart from the Carrock Mine (copper and lead, later tungsten) which only opened 5 years before their walk so they would surely have found it active and occupied.

Epic stuff, enjoyed the story, reminds me of similar adventures of my own!

Stunning photographs as always. Loved hearing about Charles and Wilkie.