Annapurna 1950 vs Everest 1953

It’s not fair to compare the small-scale French expedition to Annapurna with the large, well organised British and Commonwealth one three years later. But I’m going to do it anyway. [1000 words: 5 min

With the hype and excitement of 2023 now come to an end – oh, what hype and excitement was that? Well, I’m referring to the Everest anniversary: the first ascent on 29th May 1953 by Annullu, Band, Bourdillon, Evans, Gregory, Hillary, Hunt, Lowe, Noyce, Pugh, Stobart, Tenzing, Ward, Westmacott and Wylie. Was this, indeed, the greatest high climb of immediately after World War Two? Or should we, rather, rate the 1950 ascent of Annapurna by Herzog, Lachenal, Rébuffat and Terray?

Everest 1953 official account by expedition leader John Hunt. Illustration by the Lake District artist W Heaton Cooper

Everest is, of course, the world’s highest hill, and that has to count for something. Annapurna was simply the highest hill so far, and the first one over 8000m: though in the 1920s and 30s British climbers on Everest had climbed and died well above Annapurna’s 8091m summit height.

And Everest’s extra altitude does matter. Okay, so the added 750m is a bit lower than Coniston Old Man in the Lake District. But up in the rarified air and horrible soft snow of the ‘Death Zone’, it’s an extra day of climbing. As if Herzog and Lachenal, at the limits of endurance on the top of Annapurna, had been required to then deposit tent, food and presumably oxygen cylinders for a further summit push on the following day: well, they simply wouldn’t have made it.

The news of the British expedition’s success reached London on 2nd June 1953: the coronation day of Queen Elizabeth II – and was announced by loudspeaker to the crowds waiting for the golden coach. The conquest of the Earth’s highest point marked, symbolically, not just the new post-war Queen but the high-point after which the British Empire would begin its rapid breakup. At the same time, with a New Zealander and a Sherpa as the actual summit pair, it represented a triumph for the Commonwealth, the official replacement of the former Empire with a group of nations equal under the Queen.

contrasting cover shot: Annapurna’s over-the-top US paperback edition

Meanwhile, for the French, what was the significance of their achievement on Annapurna? Well, they had recently been defeated, in a fairly humiliating way, in the opening year of World War Two. They had been occupied by an enemy power, and regained their country only with the help of more powerful allies Britain and the US. While many had resisted bravely, even more had collaborated with the Germans.

There was national trauma to be healed. Which is one reason why, for the French nation, the achievement of Maurice Herzog and his team was huge. Indeed, Herzog’s account of the climb becomes the best-selling mountain book of all time.1

The French were a small team, exploring an unknown mountain. Two unknown mountains, in fact: they arrived with only the most misleading of maps, and didn’t even turn towards Annapurna until after weeks unsuccessfully exploring Dhaulagiri next door. They then spent further weeks exploring Annapurna, with expeditions around the mountain to work out its basic shape, followed by a first attempt up a ridgeline which turned out to be impossibly long.

Having finally worked out a feasible route, they climbed it in almost Alpine style, without oxygen, over just ten days.

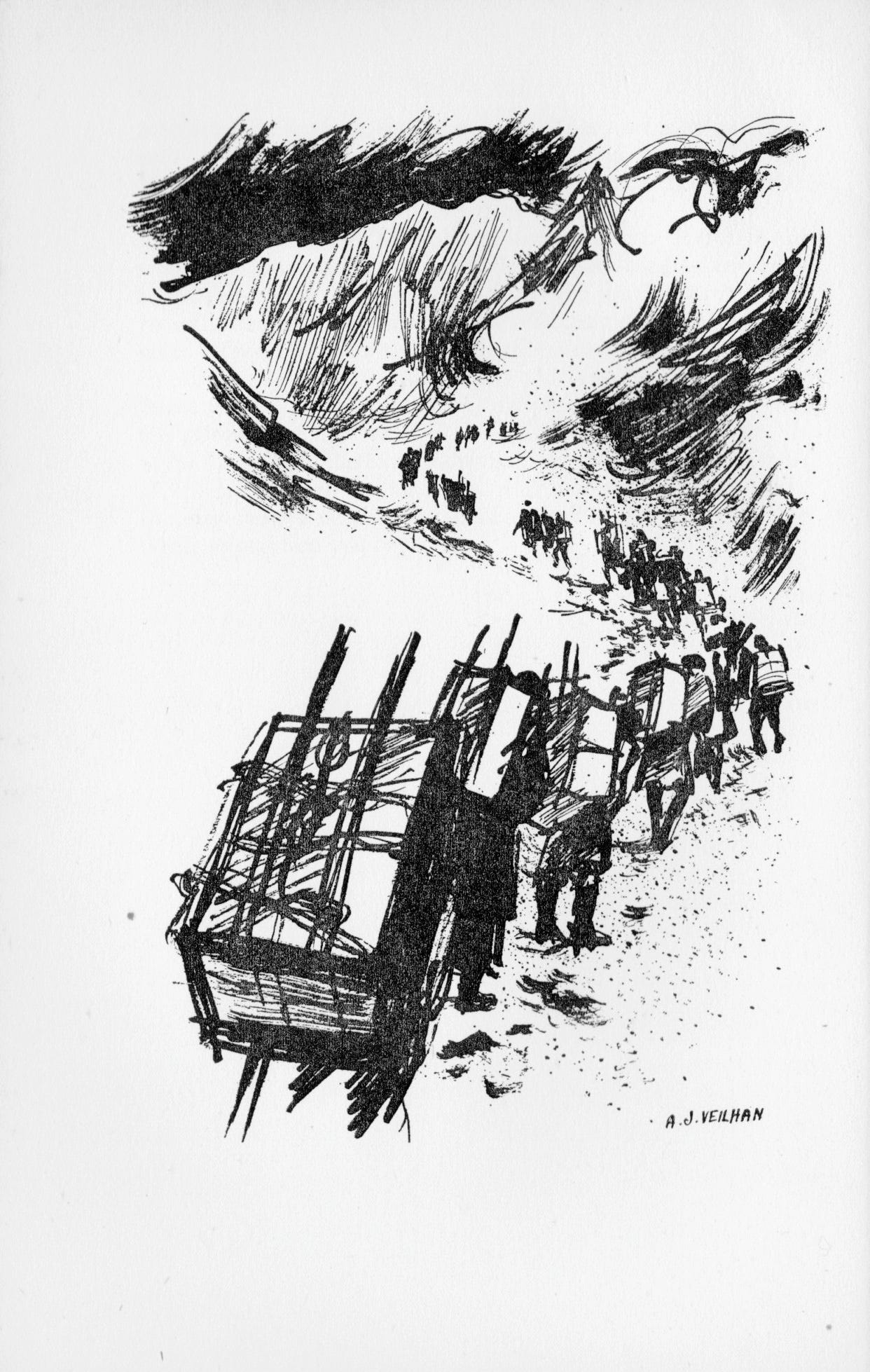

The approach to Everest: illustration by AJ Veilhan from ‘South Col’ by Wilfrid Noyce

Three years later, the British Everest expedition was very different:

With the aid of a great deal of money, [the British] organised a truly enormous expedition, consisting of no less than thirteen Europeans and forty Sherpas, all under the command of a high-ranking officer. Thanks to the huge scale of the supporting pyramid and the efficiency of the open-circuit oxygen apparatus which enabled them to breath a mixture of air and oxygen comparable to what one might find at around 6000 metres, the giant of the earth succumbed almost without a struggle.2

The searingly blunt appraisal comes from Lionel Terray, who was, yes, French, and indeed one of the climbers of Annapurna. Even so, he could also have mentioned that the 1953 expedition’s route was completely pre-explored. The Khumbu Icefall, Western Cwm and South Col had been opened as far up as 8600m, just below the South Summit, by a Swiss expedition the previous year. The Swiss, incidentally, were a climbing team of just five, with inexperienced Sherpas and oxygen sets that didn’t work.

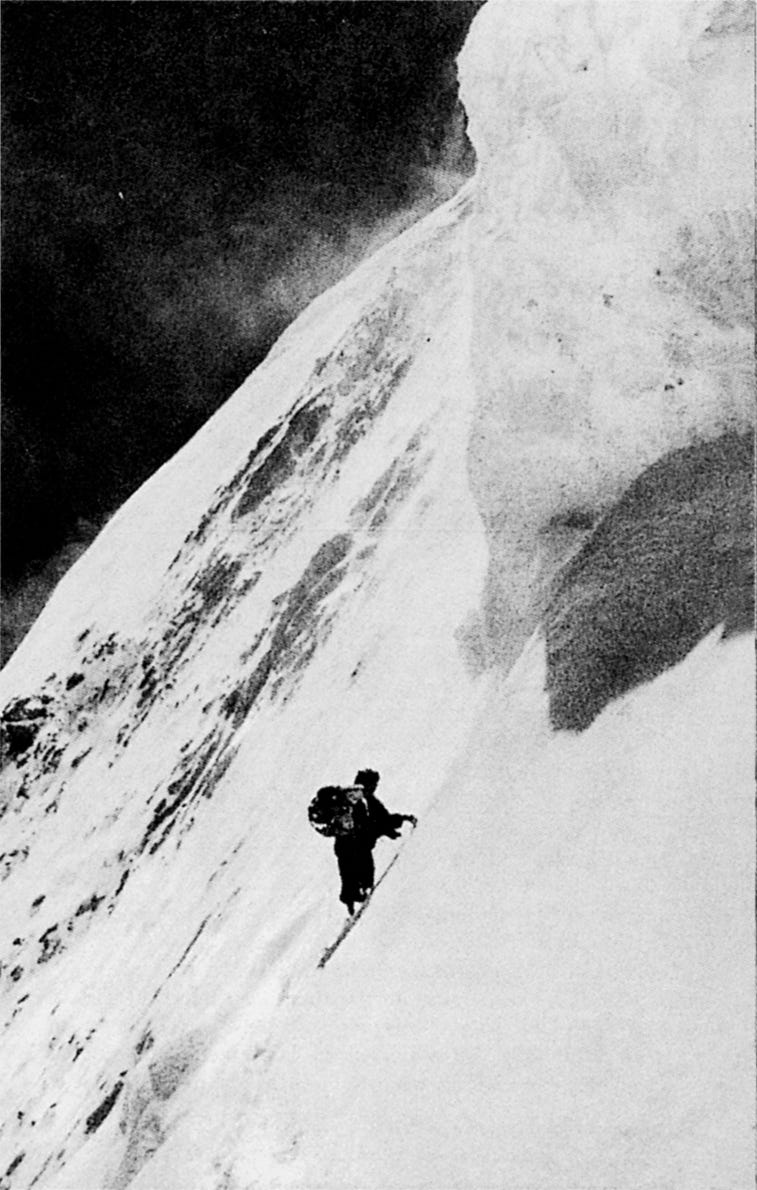

The avalanche slopes of Annapurna’s north face: 1950 expedition photo

The British expedition was made without loss of life and indeed without loss of toes or fingers: only the normal level of pain associated with slogging up steep, soft snow with altitude sickness and a heavy pack. Does this add to, or diminish, the value of their climb? Either way, it’s a testament to the military-style organisation under Col. John Hunt.

The French team, after their successful ascent, suffered intensely. The summit pair, Herzog himself and Louis Lachenal, returned to their top camp with frostbitten, hard-frozen hands, each of them having lost a glove. The following day, in cloud and snowstorm, they were escorted downwards by Lionel Terray and Gaston Rébuffat. Both of these two pushed back their goggles for better vision, but still failed to find Camp IV. They spent the night in a crevasse, and woke to a powder avalanche covering them and their gear, snowblindness for Terray and Rébuffat, and all four pairs of boots lost under the snow. The expedition then unrolled all the way back into India leaving a trail of amputated toes and fingers: Herzog and Lachenal’s feet were so damaged that they never climbed again.

Today it’s Everest that gets the attention, simply because of being higher than everything else. But many consider Annapurna as the more serious, and more desirable, of the two. Because the standard route is under avalanches and sérac fall, Annapurna is also more dangerous: possibly the most dangerous of the 8000m peaks when taken by their standard routes. One website gives Annapurna a fatality rate of 40%.

So which one wins? The Everest expedition was superbly organised and effective, and the comment by Eric Shipton is definitely unfair. Shipton’s comment? “Thank goodness, now we can get on with some proper climbing.”!

But for me, it’s Annapurna that stands out in the annals of mountaineering.

Next post: the 18th-century art of landscape appreciation

Terray quote is from ‘Conquistadors of the Useless’ p 324, translated by Geoffrey Sutton

If we want to compare the climbing of Everest in 1953 and Annapurna in 1950, the most important thing is the climbing style, which was climbed in Alpine style in Annapurna, which is of great importance. Thank you.

Thanks for your helpful article