Alexander von Humboldt climbs on Chimborazo

Me, a mountaineer? I'm only here for the barometric readings... [1500 words 7 mins

Before Samuel Taylor Coleridge climbed Scafell in August 1802; yes, people were going up mountains, but they didn't have much idea why. So they had to pretend it was all about the science: the effects of altitude, the exact blueness of the sky, the readings on the aneroid barometer.

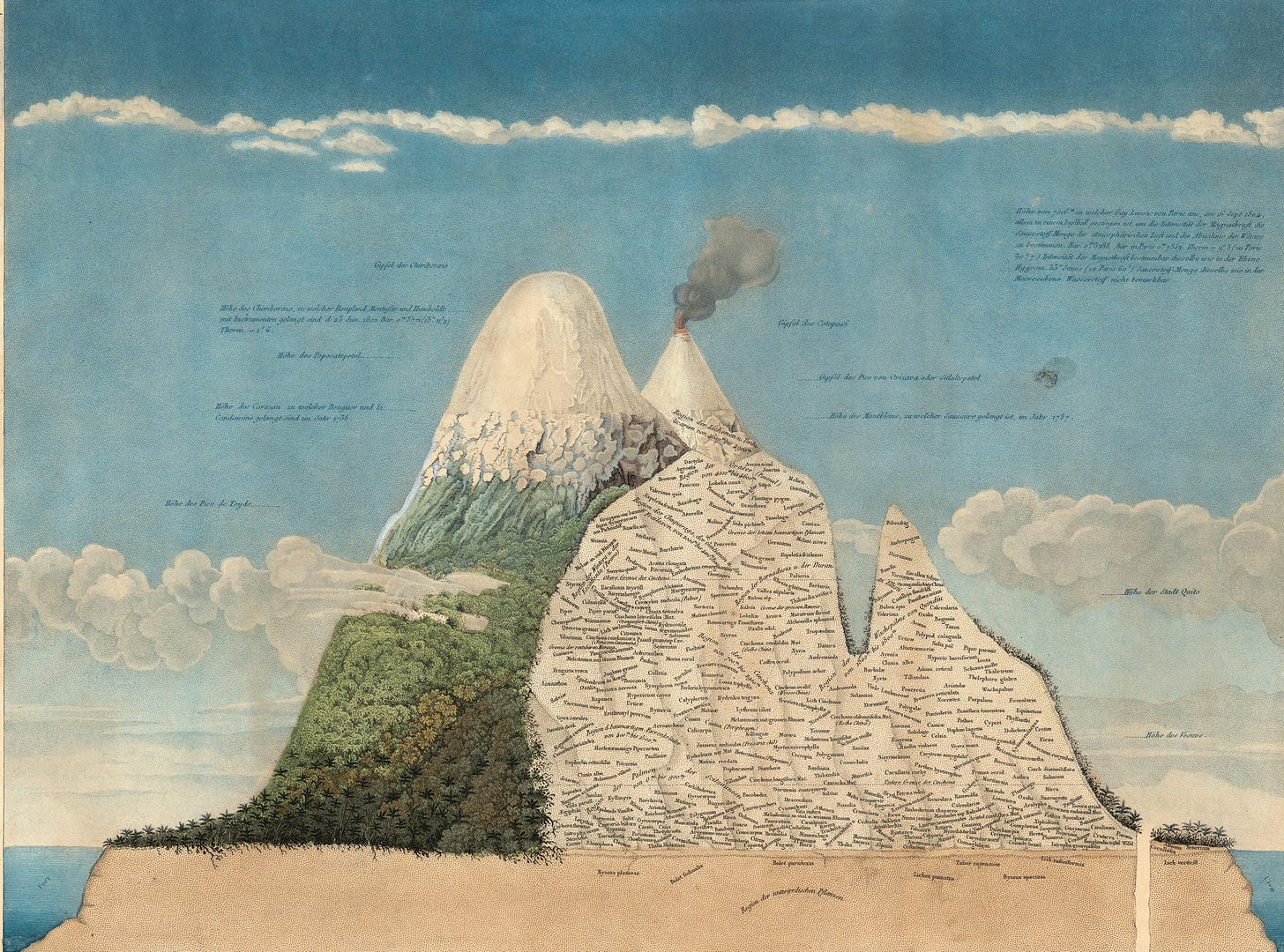

Well, that’s the story. But for a man called Alexander von Humboldt, it really was all about the science. The summits as such scarcely mattered: the tops of mountains are seriously short of interesting natural history.

But he went up them anyway. And in June of 1802, two months before Coleridge’s Scafell walk, he set off up the 6263m volcano Chimborazo in the Andes – to achieve the highest recorded altitude of any human being so far.1

Alexander von Humboldt was born in 1769, in Prussia, into the wealthy lifestyle of the minor nobility. Raised by expensive and fashionable tutors – and those tutors being of the science-loving Enlightenment tradition – even from childhood he was a naturalist. As he reached adulthood he added in geologist, explorer, and general Enlightenment all-rounder.

But life wasn't all science fun. In his work as a mine inspector in the Fichtel Mountains he bumped up gold production by 700% and set up, with his own funds, a technical school for the miners. Meanwhile his close friends included the English naturalist Sir Joseph Banks, the poet Friedrich Schiller, and the poet and naturalist Goethe.

Never close to his family, when he was 29 the death of his mother allowed him to set off on his ultimate ambition: a five-year expedition to South and North America.2 His companion on the trip was a young French botanist called Aimé Bonpland. Humboldt seems to have been gay, and the two, who spent five years travelling together, may well have been lovers. It would be nice to think so, anyway.

On the way across the Atlantic they climbed Tiede, the 3715m volcano that’s the high point of the Canary Islands (and also of Spain if you count the Canaries as being part of Spain). Their stay in Ecuador was marked by the ascent of another volcano, Pichincha (4784m). Nearby Chimborazo was considered as the highest mountain on Earth, which it actually is due to the equatorial bulge in sea leval and the earth being shaped like a slightly sat-on tangerine.

Humboldt wasn’t aware that the Romantic poets in the English hills were currently elevating mountain-climbing into a Thing. So he was a bit surprised that his attempt on Chimborazo was considered more interesting than his five years of poineering natural history during which he discovered dozens of plant and animal species, settled the exact position of Acapulco, nearly killed himself dissecting an electric eel, and observed the transit of Mercury in front of the sun.

If the endeavours of travelling natural philosophers, who strive to climb the higher summits of the earth, is scarely rewarded by a serious scientific interest, there is, on the other hand, an active popular participation in such endeavours. Chimborazo has been the wearisome object of all inquiries addressed to me since my first return to Europe… The thoroughly exploring of the most important laws of nature, the most vivid delineations of stratified zones of plants and differences in climates, were seldom capable of diverting attention from the snow-clad summit.

So he specially wrote it up in a letter during which he carefully left out all the natural history stuff, for the sake of those strange people so interested in summits.

Except, he didn’t. The details of his ascent are buried like the larvae of some exotic insect within 20 dense pages of biological deposits. Digging through them, only a few paragraphs are devoted to the actual climbing.

On the 22nd June they set out from the plain of Tapia, altitude 8898 Paris feet or 1483 toises. (Okay, that’s 2642m.) They cross a desert plain of cactus and the willow Schinus molle, grazed by wild llamas, to the native village called Calpi at the foot of the mountain. Altitude now 2887m (I’ll convert out the Paris feet from now on).

The next morning they head up the mountain’s south-southeast side, accompanied by mules and native guides. Stepped plains lead up to 3480m. The going underfoot is disappointingly grassy, but Humboldt spots a few pink gentians Gentiana cernua (now named as Gentianella cernua.) The summit’s in cloud, so despite the lovely flat ground for setting up the baseline and theodolites no trigonometry is possible.

From the high plain of Sisgun the mules plod on upwards to a tarn called Yana-Coche at 4000m. Here they come onto fresh snow, and leave the mules. Another 250m up, and the going gets serious: great walls of columnar volcanic rock rise across the slope. The snow being impossibly soft and deep, they take to a narrow rock ridge. Not great rock for climbing: very weathered and crumbling, black, vesicular basalt.

At 4700m, “all entreaties and threats were unavailing” – all but one of the guides turned back. The rest of the party headed on up into the mist. The ridge was just 10 inches wide. On the left, soft snow lay over rock, quite steeply at 30°. On the right “our view sank shuddering 800 or 1000 feet into an abyss out of which projected, perpendicularly, snowless masses of rock”.

So there was nothing for it but scrambling on up the crumbly ridge. “As the rock was keenly angular, we were painfully hurt, especially in the hands.” Also the fleabites (Pulex penetrans) on his feet were rubbing uncomforably inside his boots.

At 4500m, Aimé Bonpland caught a butterfly; at 5000m, they spotted a single fly. At 5700m, still in the mist, the temperature measurements in the air and the sand underfoot were at 2° and 5° respectively. Another hour, and they’re suffering nausea, giddiness, and difficulty in breathing; bleeding from the gums and lips, and bloodshot eyes. Symptoms they’d experienced before, on previous volcanoes: normal effects of altitude, apart from the bleeding, which could be down to extreme sunburn, given the requisite Factor 50 wouldn’t be invented for another 120 years.

And then the mist cleared above them, to show them the summit dome, apparently within easy reach. But it wasn’t. The ridge ran up to a gap 120m deep and 15m wide, with deep soft snow on the ridge flanks to either side. This was as far as they were going.

The barometer put them at 3214 toises or 19,286 Paris feet: as he reckoned, just 1224ft short of the summit. That would be 5727m – so that if his readings were right there were actually still 550m of height to climb. Also they had wet feet from all the melting snow.

“We remained but a short time in this mournful solitude, being soon again entirely veiled in mist.” They hurried down by the same route, pausing only to fill their pockets with heavy rocks (all right, geological specimens). They passed through a hailstorm, then falling snow. Still early in the afternoon they rejoined their mules, after just 3 1/2 hours above the snowline. By 5pm they were back at Calpi.

These numbers don’t altogether make sense: 1700m of ascent and descent in 3 1/2 hours would be considered good to average by a really strong fellrunner. Today, Chimborazo is a two day mountain hike with Alpine grade PD, ‘peu difficile’. From a high camp at 5340m it’s off again at midnight to complete the 12-hour up and down before the afternoon stonefall gets too serious. There’s crevasses, and tricky routefinding. The upper icefield is steep enough to really need two iceaxes, says a friend3 who’s one of many to have almost climbed Chimborazo before being turned back by not being acclimatised enough for the 6000m altitude.

Never mind. Humboldt certainly climbed jolly high. And returning still alive from his trip made him the first celebrity scientist. More plant and animal species are named after Humboldt than after any other human being. Including (just in English nomenclature) the Humboldt squid, Humboldt penguin, Humboldt’s lily, Humboldt’s hummingbird and Homboldts hog-nosed skunk. Together with a bay, a glacier, a mountain range in Nevada, and an ocean current in the South Atlantic.

Though there’s evidence that Inca priests and their victims had climbed even higher, with human sacrifices having taken place on the 6723m summit of Llullaillaco. (That snowy, cinder-covered hill is more than just a Hell of a place. It is in fact a six-L of a place.)

Humboldt’s trip would end up being four months longer than the even more famous voyage of Charles Darwin 32 years later.

Thanks here to Chris Scaife of the Outdoor Writers and Photographers Guild, who climbed (most of) Chimborazo several years ago..

Sam Matey wrote about Humboldt once I believe. He made a good argument that Humboldt was one of the most interesting and able naturalists to have ever graced the annals of history.

Great writing Ronald. You keep up a very high standard of wit and erudition! Thanks.