Aleister Crowley, magus and mountaineer

A brief round-up on the most evil man to ever climb Kanchenjunga [1300 words, 6 mins

According to UKclimbing.com, there are 13 ways up the Napes Needle. But for those of a historic bent (and in this case, bent is the appropriate word), a route starting to the left of The Arête and then crossing it is credited to one E A Crowley in 1893. This is indeed Aleister Crowley, known as the Great Beast. Because, besides being the wickedest man alive at the time, Crowley was a pioneering climber and mountaineer who made the first-ever attempts on K2 and Kanchenjunga.

The Nape’s Needle, on Great Gable, Lake District. The obvious Wasdale Crack in the shadowed front face is the usual way up the lower two-thirds of the Needle. The Crowley Route, with characteristic perversity, starts at the foot of this, works downwards and to the right to cross The Arete (the 2nd most popular route, right-hand edge in the photo) then works round to cross the third most popular ascent line, the Lingmell Crack which is the Wasdale Crack seen from the other direction.

I remember nothing of Crowley’s route, so it’s been erased from my brain either by the emanations of Evil or else, more likely, by the greater Beastliness of the final two blocks that form the top of the pinnacle. (Crowley’s Route today is graded at V Diff, but the Needle as a whole comes in at Hard Severe.)

According to the image file (Wikimedia Commons) this is Crowley on the approach to K2 – but to me it looks like Goats Water under Coniston Old Man

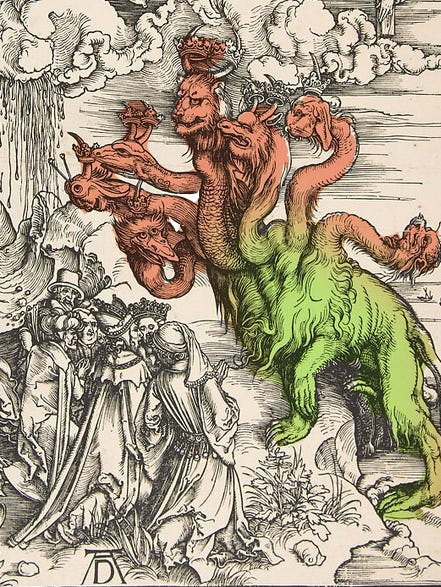

Born in 1875 and brought up among the extremist Christian sect of the Plymouth Brethern, Crowley realised early on that his favourite Bible person was the Great Beast of the Apocalypse, the seven-headed monster that was to battle with the angels at the end of time, also known as 666. Going up to Trinity College at Cambridge (famed, among much else, for its roof-climbing potential) he quickly switched from the Natural Science course to the Unnatural Sciences: drugs, sex, yoga, black magic, astrology, pornography and – it pretty much comes with the territory – mountaineering.

The Beast of the Apocalypse, by Albrecht Durer. “Oo-be-doo I want to be like you-oo-oo, walk like you talk like you too”

In pursuit of his precept ‘do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the law’, he debauched minor film stars of both sexes, betrayed his friends, and became an alcoholic and heroin addict. And Crowley remains the only person known to have induced bustups within both the Alpine Club and also the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn.

Golden Dawn’s members included the poet WB Yeats1, Irish revolutionary Maud Gonne, novelists Arnold Bennett and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, and according to rumour ‘Railway Children’ author E Nesbit. A forward-looking set of evildoers, the order admitted women and men on an equal basis. But sufficiently locked into committee-style management that it could be torpedoed by a single obnoxious individual (Aleister, who else?) More robust and practical, the Alpine Club simply threw Crowley out.

And Crowley’s badness extended even to his spelling. “Aleister”? He grew up as Alexander. But in the late Victorian era, it was fashionable to be not only bad, but also Scottish; so in 1899 he bought himself a small estate in Invernessshire, Boleskine Hall (three syllables, Bole-Eskine). Thus becoming an authentic and actual Loch Ness Monster.

A glimpse of the Loch Ness Monster, from the old pier below Boleskine, August 20072

As he studied his magical books, the sky darkened at midday so that candles had to be lit, and the lodge keeper went mad. We might take the darkening of the sky as a normal Scottish raincloud. But as late as the 1970s a villager in Abriachan, on the other side of the loch, showed me the rowan trees the villagers planted acros their gardens to protect themselves against the ‘Beast of Boleskine’.

Apart from seducing his neighbours and brightening the Invernessshire scene with various exotic mistresses, Crowley contributed to local life by prankishly reporting to the Society for the Suppression of Vice his unhappiness over the prevalence of prostitution in Foyers. When they came back to him saying that actually, Forres being quite a small place, there weren’t any prostitutes at all, he explained – yes, that was precisely the poblem… As an early environmentalist (or, perhaps, renewable energy opponent) he also made an impassioned plea against the plan to enclose the Falls of Foyers in hydro-electric water pipes.

This evil-doing is all very well, I hear you think. But what about his mountains?

As well as Snowdonia and the Lake District, with characteristic perversity the evil magus did achieve some climbs on Beachy Head with the aid of the ice-axe designed by his pal Oskar Eckenstein. Then, as the century turned, he was in Mexico practising the art of invisibility (partial success: after three months of training his image in the mirror became ‘faint and flickering’) and climbing the two sacred volcanoes Popacatapetl and Ixtaccihuatl. And then he moved on to the Himalayas.

Eckenstein-design crampons (Alex Roddie collection). I used virtually the same style in the 1970s, and in fact only replaced them a few years ago.

K2 1902

In 1902 Crowley joined the first-ever expedition to K2, led by his friend and mentor Oscar Eckenstein3. Things didn’t go smoothly. Straight away they were delayed for three weeks by the British authorities as Eckenstein was suspected of being a German and a spy (although the two Austrians in the party proceeded unmolested). Eckenstein and Crowley then quarreled over the rucksacks full of books that Aleister proposed to haul up the glacier. It didn’t help that the two Brits and the two Austrians had between them three different views on the best way up the mountain.

Over 68 days, many of them stormbound, the expedition reached 6500m (not terribly high) on the NE Ridge. In fact the alternative route proposed by Crowley, later named as the Abruzzi Spur, turned out to be the key to the mountain 52 years later. Aleister threatened the other expedition members with a revolvern; someone who, oddly enouth, wasn’t Crowley at all (one of the Austrians, a chap called Wessely) stole the emergency rations; and the expedition broke up with bad feelings all round.

Kanchenjunga from the Indian plains, by T Howard Somervell, one of the Everest climbers from 1924.

Kangchenjunga 1905

Three years later the Great Beast joined an expedition to Kangchenjunga, attacking the SW Face via the Yalung Glacier. Things came to a head at Camp V (6300m, still not terribly high4), where the expedition leader, Jules Jacot-Guillarmod, tried to depose Crowley as the expedition’s climbing leader. Crowley refused to stand down, and J-G, with two other climbers and four porters, set off down the mountain leaving Crowley at the high camp. Almost at once the descending party was hit by an avalanche. At Camp V they heard the ‘despairing cries’; three porters and a European were killed. But Crowley remained in his tent. As he wrote to a newspaper the same evening: "A mountain 'accident' of this sort is one of the things for which I have no sympathy whatever."5

With the expedition obviously over, Crowley headed down the mountain and out to Darjeeling, where he stole the expedition’s ramaining funds. Apparently Jacot-Guillarmod managed to get some of the money back ‘after threatening to publish some of Crowley’s pornographic poetry’. Though this seems implausible as Crowley would surely have been thrilled to see the filthy things6 in print.

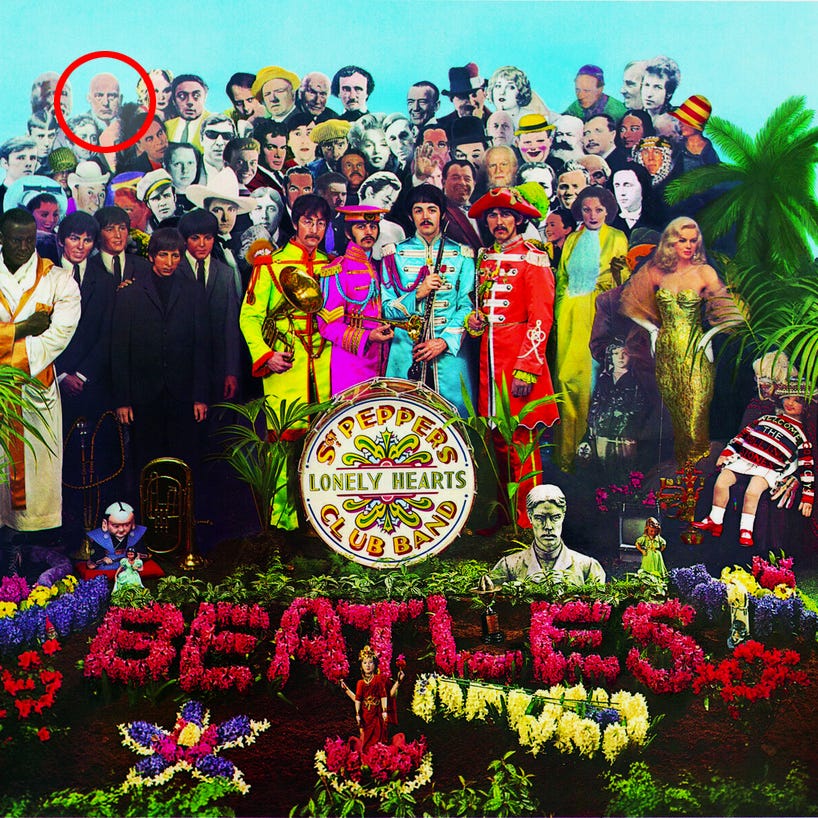

Crowley is the only mountain-climber to feature on the collaged cover of ‘Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band’ (Peter Blake 1968)

In a 2002 BBC poll of the 100 Greatest Britons, Aleister came in at no. 73, one place ahead of Robert the Bruce and 9 places up from fellow evil-doer Richard III. But, disappointinly, a full 53 spots down from gunpowder plotter Guy Fawkes. The only other mountaineers on the list is Munro-bagger Queen Victoria at Number 18.

Some pretty unpleasant people have been great mountaineers: Don Whillans and Dougal Haston spring to mind, and Edward Whymper seems to have been an unattractive fellow as well. In today’s celebrity circles, nastiness works for some as a career plan. But when it comes to pure, unadulterated evil, none can match the original monster of mountaineering, the Great Beast Aleister Crowley.

Yeats’ fine but mystifying ‘The Second Coming’ is derived from a drug-induced vision within his Golden Dawn fun-time.

The first encounter with the Loch Ness monster was back to the 6th century AD, when St Columba was crossing the River Ness. One of his companions was attacked by a water beast. When the saint ordered it to go away, it did. The onlookers, pagan barbarians whose friend had already been eaten, promptly converted to Christianity. The account was set down 100 years later by Adomnan, an abbot of Iona. For those of a sceptical turn, it all sounds suspiciously like an earlier incident from the life of a different holy man, St Martin of Tours, and also like a story about how Christianity took over a site where human sacrifice had been offered to a river god.

However, later confirmation came during the Lisbon earthquake of 1755. A shock wave, freakishly magnified along Loch Ness, sent breakers crashing against the shore at Fort Augustus – clearly Columba’s monster was still down there disturbing the water. The photos from the 1930s are fakes using a cardboard cutout – unlike my one above, produced with an early version of Photoshop.

Oscar Eckenstein comes across as a genuinely likeable character – provided, that is, you happened to be Aleister Crowley. Others found him obnoxious: by the time the two of them met, Eckenstein had his own independent quarrel with the Alpine Club. As a climber he’s noted for inventing the early-modern version of the ice-axe and crampons. That in itself is an arguably obnoxious act as destroying the Noble Art of cutting steps in steep snow – as late as the 1960s, in Scotland, the use of Eckstein-style crampons was still being disparaged.

But Crowley was able to claim an ascent as highest-human-so-far to an impressive 7500m. History is divided on this one. Crowley says he did it, everyone else says he didn’t.

Quoted in ‘Fallen Giants: A History of Himalayan Mountaineering from the Age of Empire’ by Maurice Isserman, Stewart Angas Weaver, Dee Molenaar

And as any Ransome scholar will know, Goat’s Water is a plausible stop on the way to/from Kangchenjunga, not K2.