Tors for thought

Grim granite lanscapes – Dartmoor, the Cairngorms – have the silliest of decorative ornament up on top: the granite tors. [1300 words, 5 mins

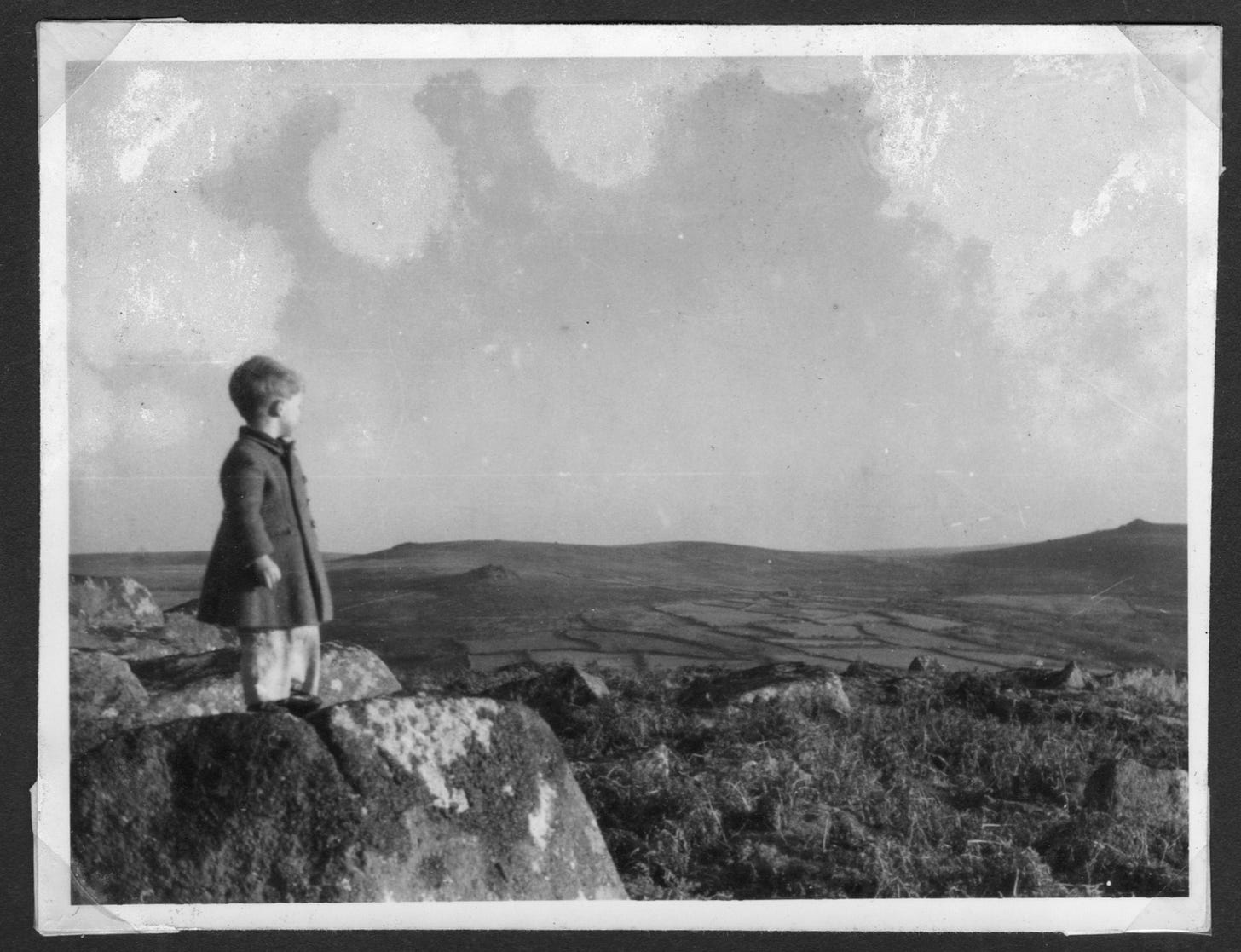

My Dad planned to enrol me into the Scottish Mountaineering Club, as his own father had once enrolled him. So he kept records of all my early ascents. This lets me determine that, when I first conquered Pew Tor (320m) on the western edge of Dartmoor, I was a big one year and ten months old.

Me on my very first mountain [Photo: Derwent Turnbull]

Pew Tor is a place of magic where you can run around and lose sight of your Mummy in no time at all. There are piles of granite, shaped like really big cow pats, and as rough as your Daddy's chin. One of them has a mighty chasm or ravine that you stride right across to reach the highest point. And that high point is a basin, a stone dip where you lie below the rock rim with nothing to see but sky – until you peep over the edge to see if Mummy's still looking for you. And the chasm's just as great at ground level, where you stomp along the ravine floor on little quartz crystals fallen from the rock.

But another of the mini-tors goes even better. There's a gap in it, a tunnel, where, if you're little enough, you can creep around the corner and come out on the other side of it.

I was little enough.1

Great Staple Tor, Dartmoor (Wikimedia Commons)

Dartmoor’s 950 sq km have more than 150 tors. When you grow up on the edge of Dartmoor, where every slightly higher point has a rocky tor on top of it, then you think tors are ordinary. They aren’t. They’re common on Bodmin Moor just next door, and away up north in the Cairngorms. And that’s about it. My current home country of Galloway has upstanding chunks of granite like Cairnsmore of Fleet, and Cairnsmore of Carsphairn, and, yes, Cairnsmore of Dee as well. Each of them is a wide, boggy-topped, heathery-sided, rounded lump of mountain reflecting the shape they were born in deep under the ground, as England was slowly squashed in underneath the Scottish Borders. Tors? Totally absent.

Barns of Bynack, Cairngorms

And the same, roughly speaking, goes for the rest of the world. The Wikipedia page, after listing 50 on Bodmin Moor, and not trying to count up the Cairngorms, lists three in Africa, five in Germany, one in Malaysia, the Telangana and the Rayalaseema regions of southeast India, and a handful in the USA.

Black Tor, Dartmoor. The 18th-century theory was they’d been built by Druids for doing human sacrifices on.

Tors that Oughtn’t

Leaving aside all the tors that aren’t around in the rest of the world, the strange thing about the UK ones is that a major lump of them, scattered across the Cairngorm Mountains, really oughtn’t to exist either. Because, well, we know that the Cairngorms have only just emerged from underneath hundreds and hundreds of metres of ice.

There are really only three options. And none of the three makes sense:

• The tors have all formed in the brief 20,000 years since the end of the Ice Age.

• The tors somehow survived underneath all that ice.

• We’ve got it all wrong about the Ice Age.

Yet it took until 1980s for anyone to ask the obvious question: how come?2 And a few years after that to answer it.

Walking towards tors on Beinn Mheadhoin, Cairngorms

There’s a few clues:

1. The tors of Dartmoor sometimes form elegant tottery towers. The ones in the Cairngorms are rather more squat and sturdy. Dartmoor, we note, was never underneath any ice.

2. The tors of the Cairngorms are only on the flat plateaus across the very highest ground. Some of the Dartmoor ones are on side-slopes and the shallow valley floors.

3. One or two of the Cairngorm ones do look as if they’ve been shoved about a bit.

The Argyll Stone, Cairngorms. This tor does look sort of shoved over.

We’re told about – and if we’re fortunate we even tread upon – the awesome power of the moving glacier. The ice that carved out the hollow of the Lairig Ghru was like that. But the ice on the Cairngorm plateau wasn’t.

It turns out there’s two kinds of ice. There’s ice that’s hard frozen in place, and ice that’s wet at its base. Soggy-bottomed ice is lubricated, and starts to slide. The sliding creates friction heat, and melts some more lubricating water: a feedback mechanism so that ice that’s once started to slide begins to make a habit of it.

The ice-slide may have started down some shallow landscape dip. But sliding ice, with its frozen-in boulders, is an awesome grinder. Soon the shallow dip becomes a shallow valley. Snow blowing across the plateau ends up in the valley, adding itself onto the sliding ice; the sliding ice deepens, its grind becomes even more powerful. And its valley floor, now hundreds of metres down, gets even more meltwater to lubricate the new glacier’s base.

Up on the plateau, on the other hand, ice flows as a solid. Its base is frozen down, the ice as a whole creeps outwards at a metre or two in the year. And so the plateau ground is uneroded, gently rolling, with the little River Dee running down the same shallow valley it had before the ice came, and tors only slightly battered about. And then you come suddenly to the plateau edge, and look down 600m into the deep ‘U’ of the Lairig Ghru, erratic boulders and drumlin humps in its bottom. Beside you, the Dee leaps down a crag of ice-chewed granite. Plateau (dry-bottom ice) and chasm (wet-bottom ice): the combination of the two is the Cairngorms.3

The Cairngorms, seen from the north. There was frozen-down icecap on the plateau; moving glacier ice gouged out the Lairig Ghru pass (right of centre). Small corrie glaciers carved the front edge.

Shrinking glaciers are just one of the effects of climate change. But they’re also, in a small way, one of the forcing causes. Glaciers are white (or at worst dirty grey) and reflect sunlight back into space: the bare ground that replaces them absorbs and retains that heat. Which is why scientists at Cambridge4 are looking at the way meltwater lubricates the moving glacier to see if humans could slow down that process so as to preserve a bigger glacier.

By adjusting the flow of meltwater underneath and inside the ice, it might be possible to persuade the Greenland icecap to stay as icecap, rather than sliding off the side as glaciers. Thus preserving any granite tors that may be lurking underneath it – as well as saving London, Kolkata (Calcutta), Shanghai, New York and Tokyo from the rising sea.5

And the tors themselves? They are formed underground: granite rotted by plant juices trickling from above at a time when this part of the world was warmer. They’re then excavated by soil creep during the chilly moments around the edges of the ice age. Come across them on the Cairngorm plateau and they’re as odd as a bobblehat perched on a sculpture by Henry Moore. But work out where they’ve come from, and how they’ve survived, and they’re a whole lot odder than that. Really, there’s only one appropriate response.

Tor blimey!6

Watern Tor, Dartmoor

This is an extract from my ‘Hillwalking Bible’, to be published by Bloomsbury / Conway in May and which I now ought to be planning some pre-publicity for.

In the Scottish Mountaineering Club Journal issue 174 (1983)

Adapted from the section ‘The Cause of Tors’ in my geology book for hillwalkers ‘Granite & Grit’, now out of print.

In the Department of Applied Mathematics and Theoretical Physics in Wilberforce Road. News release here.

According to the EU’s European Climate Adaptation Platform, the cities where more than four million people are expected to suffer coastal flooding during the 2070s are: Kolkata (Calcutta) 14m, Mumbai (Bombay) 11m, Dhaka 11m, Guangzhou 11m, Ho Chi Minh City 9m, Shanghai 5m, Bangkok 5m, Rangoon 5m, Miami 4m, Hai Phong (Vietnam) 4m, Alexandria 4m. New York has 3m, Tokyo 2.5m.

For US and other readers: this very mild expletive of UK English is said to be a corruption of ‘God blind me!’

Thanks, James! There'll probably be a geology themed post every couple of months, along with the ones about the Lake District, early Alpinists, the Romantic poets and Rannoch Moor...

I love this one. Interesting to understand a bit more about the formation of the tors - and just how special/unusual they are. On our tour of New Zealand, we’ve been enjoying the glacial landscape features, which are often more obvious than in the UK. The work that the Centre for Climate Repair is doing is exciting, too. Thanks for sharing!