Three Peaks of mountain writing

Mountaineering throws up fundamental questions about friendship and obsession, about sport and ethics, about life and death. It also throws up some fine writers. Here are three of them. (4 mins read)

Now for our mountain sport. Up to yon hill.

Your legs are young

Shakespeare, Cymbeline III 3

This newsletter will be about mountains. About walking across them, climbing up them, and in particular about writing about them. It will roam freely from the Cotswolds to Kangchenjunga, over the last quarter-millennium when heading to local high points of the world has been a thing.

Because walking about on hills is a crucial human act. It taps into instincts around hunting down an elk, accessing the very best of the bilberries, defending the territory of the tribe, and sneaking into the territory of the other tribe and having it off with their attractive young people.

Or is it? It's hard to see the habit of going up hills as having survival value when it so often leads directly to death. So, is climbing mountains a cultural act, like folk dancing or wearing bell-bottom trousers? Or could it simply be about showing off: the habit of surviving in perilous situations making one more attractive for breeding purposes?

And perhaps the most paradoxical aspect of mountaineering: it's fun, despite – or even, conceivably, because of – being uncomfortable, painful and frightening. The many different forms of misery enjoyed on commercial expeditions to Everest are just the most pointed example. In a less lethal way the same applies to anyone who bags Munros in the rain – which is all of us who bag Munros.

So mountaineering throws up fundamental questions about friendship and obsession, about sport and ethics, about life and death. It also throws up some very fine writers. For the first waymark post, here, briefly, are three that mean a lot to me.

Samuel Taylor Coleridge: fell notebooks

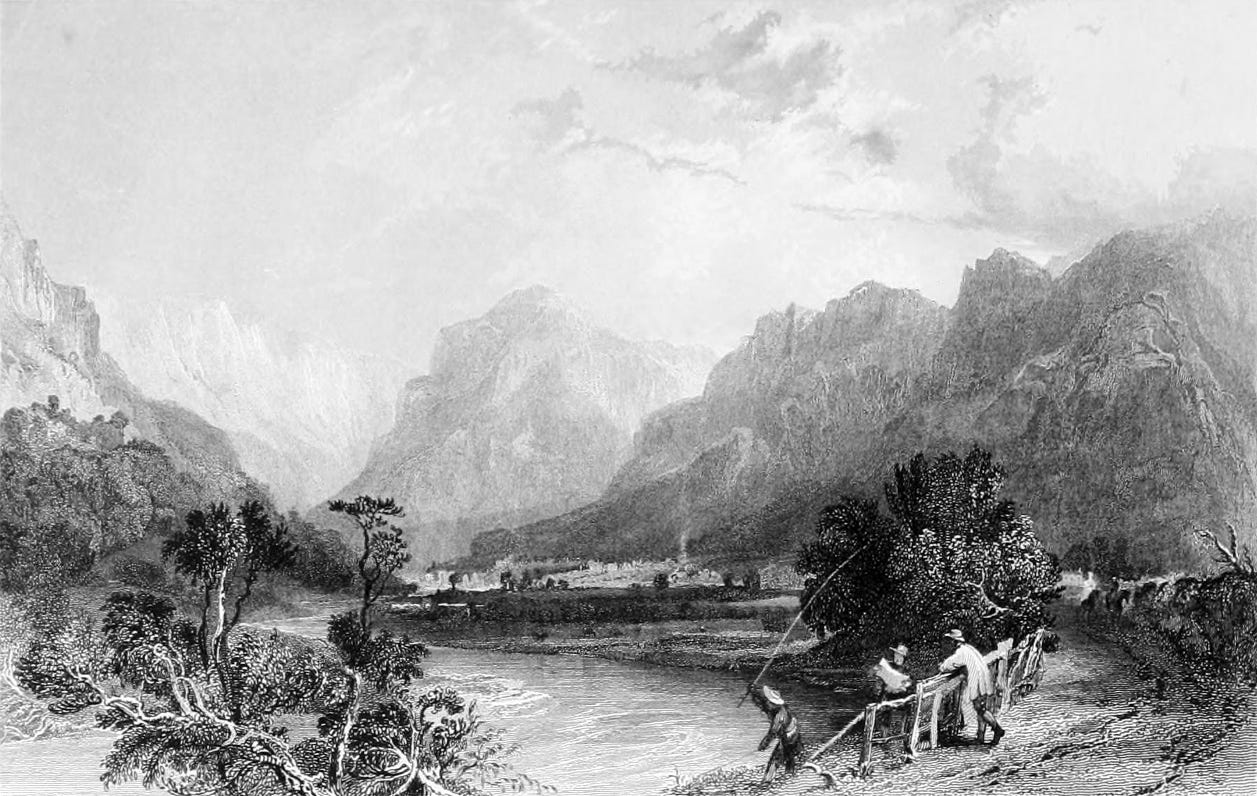

Eagle Crag, Borrowdale, by Coleridge’s contemporary William Westall

On 2nd August 1802, the poet Coleridge crossed Scafell in the course of a nine-day hike out of Keswick. He took an adventurous way down: straight towards Mickledore, dangling by his hands over little cliffs, to arrive, irreversibly, on the sloping ledge of Broad Stand. Where he lay down, looked at the sky, and laughed at himself for what should really have been a life-ending experience. This outing has been considered as the first fellwalk: the beginning of hills experienced in the same way, for the same not-fully-reasonable reasons, as we’re still going up them today.

But more important even than the walking – the writing. The letter he started at Scafell summit to his lover Sara Hutchinson, and finished later by the warm fireside at Taws farm in upper Eskdale. The many volumes of his fell notebooks, now preserved in the British Library. STC remains the first, and still to my mind the finest, writer of fellwalking in the Lakes.

I had a glorious walk – the rain sailing along those black crags and green slopes, white as the woolly down on the under side of a willow leaf, and soft as floss silk. Silver fillets of water down every mountain from top to bottom that were as fine as bridegrooms.

Alfred and Mary Mummery: My Climbs in the Alps and Caucasus

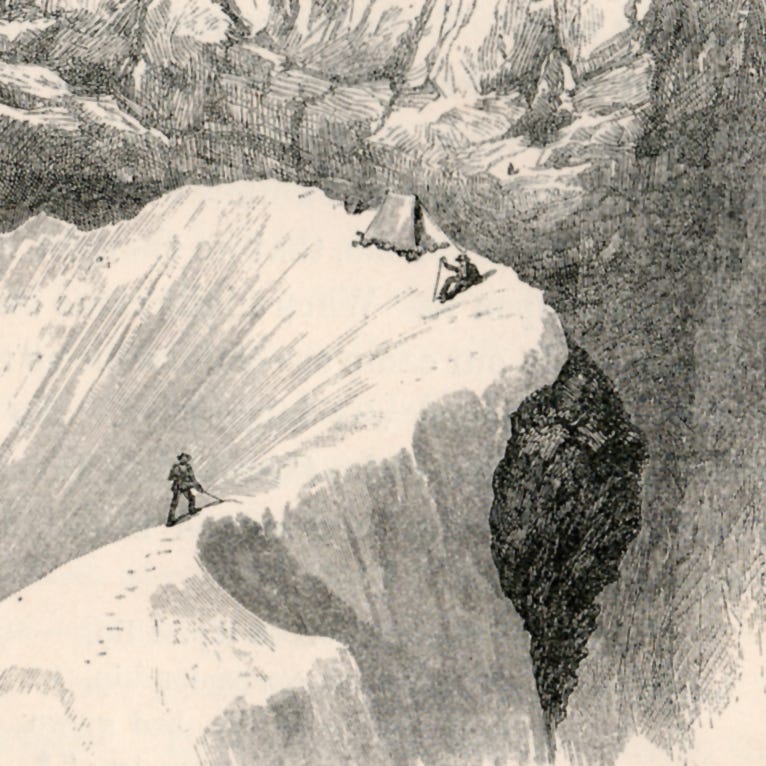

Col du Lion: Edward Whymper, from ‘Ascent of the Matterhorn’

They used to say that all of it: the 30-mile hikes across Wales, the rock-climbs on Pillar Rock, the little ice gullies on the side of Ben Nevis – that all of this was just practice for the Alps. Practice for the pre-dawn glacier, the perfectly formed snow arête, the granite rock-tower blocking the ridge, the 4000m summit with cloud filling the valley below and a hundred more mountains striding away across France, Switzerland and Italy.

And you know what? When they said that, they were right.

The most joyful account of this most archetypal activity comes with Mummery’s ‘My Climbs’ – his first ascents on the Chamonix Aiguilles, the Zmutt Ridge of the Matterhorn, and the Teufelsgrat on the Taschhorn; that last one being written up by his wife and climbing companion Mary.

Gradually my attention was riveted by the Col du Lion, and it was brought home to my mind, that no more difficult, circuitous, and inconvenient method of getting from Zermatt to Breuil could possibly be devised than by using this same Col as a pass.

WH Murray: Mountaineering in Scotland, Undiscovered Scotland

Buachaille Etive Mor (RT photo)

Scottish ice climbing, between the wars, with nailed boots, a single iceaxe, and a slater’s pick – it’s the most dangerous, miserable, and altogether exhilarating sport so far devised. That’s how it appears, anyway, when written up afterwards, on toilet paper with a stub of pencil, crouched in the latrine of a prison camp in wartime Germany.

Within twentieth-century mountain writing, harsh and unemotional as it tends to be, Bill Murray comes across as a dangerous romantic – this influenced, perhaps, by the Eastern mysticism that helped him through those years as a prisoner of war. And his joy in the hills of Scotland extends far beyond the grim gullies of Glen Coe, the Nevis rock-climbs in the rain, to winter camps on the Aonach Eagach and even a summer stroll across Rannoch Moor.

When we walked across the plateau, it became very clear to me that only the true self, which transcends the personal, lays claim to immortality.

Not just those great writers of the past and the present: when we write about mountains, and mountaineering – the beauty, the misery, the achievement and the failure, the utter pointlessness of it all – well, we’re writing about life.

So never mind the Hokey-Cokey. This is really what it’s all about.

Next instalment, Wed 20th December: Where the Crow Starves: TS Eliot crosses Rannoch Moor.

Thanks for your good post, it can be said that climbing is a combination of morality, danger, writing, and adventure, which actually brings back the human being to his original.