Romantic chasms

Coleridge, Kubla Khan, and the Somerset Coast Path [2200 words 15 mins

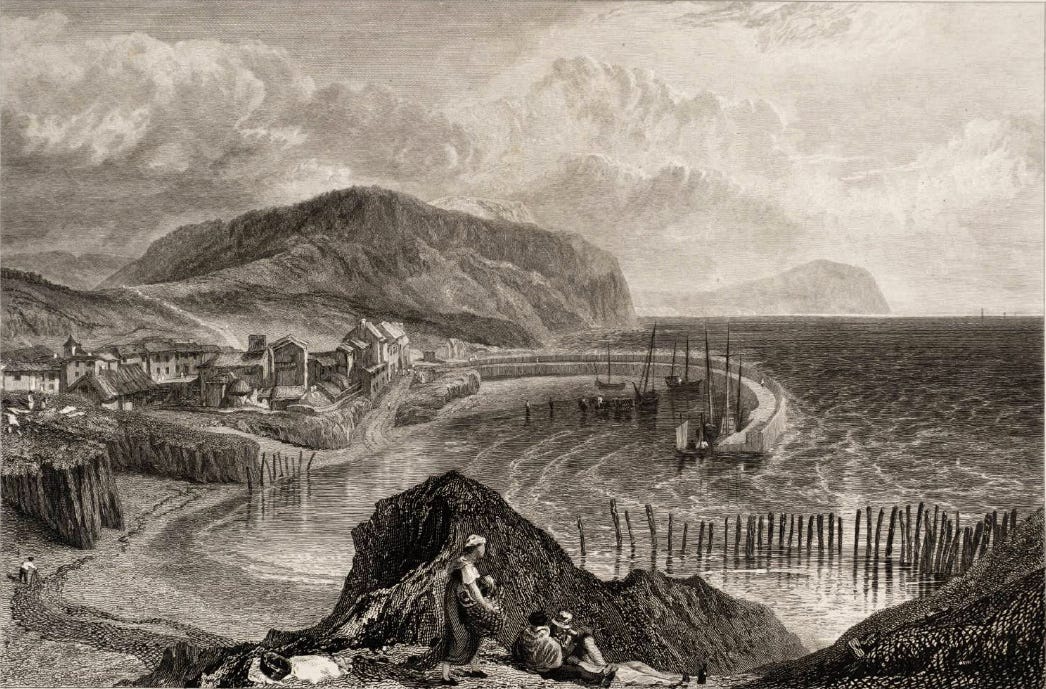

Twelve miles in, I left the seaside town of Porlock under an ornamental arch with stone battlements. Ferns erupted like green volcanoes out of brown leafmould; the sound of the unseen sea-waves seeped between the beech trees. Earth steps bent towards the isolated church at Culbone, and I started to recite in my mind the lines of Kubla Khan.

So twice five miles of fertile ground

With walls and towers were girdled round

And there were gardens bright, with sinuous rills

Where blossomed many an incense-bearing tree

And there were forests ancient as the hills

Enfolding sunny spots of greenery.

But I only got as far as the shadow of the dome of pleasure floating midway on the wave. Coleridge's opium dream was disturbed by a 'person from Porlock'. Mine was interrupted by catching up with one of my 500 fellow walkers, also just up out of Porlock. This particular person from Porlock wanted to discuss the distance to the next checkpoint, and our prospects for the day ahead, not to mention the night ahead and the following day.

Every year, on the last weekend of May, the Long Distance Walkers' Association organises its headline walk. Each year it's in a different part of Britain; but each year it's the same hundred miles, on paths, moorland, and open hill, with about 15,000ft or 4500m of ascent – which is half way up Everest, but even so isn't all that much when spread over the hundred miles. A dozen checkpoints offer food and drink along the way. Otherwise, the walk is continuous, with no overnight breaks. From a 10am start, strong runners aim to finish within 24 hours. Strong walkers finish by the end of the second day. Those who take it to the 48-hour time limit will walk, stumble and stagger through a second night: and some will experience Coleridge-type hallucinations.

This proposition attracts 500 starters each year – usually, the event is over-subscribed. Depending on the weather and walking conditions, about 300 of them will finish within the time limit.

Two hundred years earlier, the poet of Kubla Khan was also a long-distance walker. Samuel Taylor Coleridge and William Wordsworth, popularly known as the Lakes Poets, started their writing and their walking here in Somerset. We were, in fact, following a favourite challenge walk of Coleridge's. Visitors to his cottage at Nether Stowey were walked 37 miles (I just measured it), over the Quantocks and along the Exmoor coast into Devon, to finish by moonlight at the Valley of the Rocks, near Lynton.

The essayist William Hazlitt was another walker:. He walked from Wem to Nether Stowey to visit Coleridge. Yes, that’s Wem in Shropshire. Well, he did really want to meet up with Coleridge, and he was too poor for a horse. But also, he was an 18th-century Romantic. And 18th-century Romantics, they went for walks. Best of all, a walk with Samuel Taylor Coleridge.

“The light of his [Coleridge's] genius shone into my soul, like the sun's rays glittering in the puddles of the road.”

Hazlitt has even left us a record of Coleridge’s way of going for a walk. “I observed that he continually crossed me on the way by shifting from one side of the foot-path to the other. This struck me as an odd movement; but I did not at that time connect it with any instability of purpose or involuntary change of principle, as I have done since. He seemed unable to keep on in any strait line.”

Three miles up the path from Porlock comes tiny Culbone Church, its bell-tower less than a third of the way up the brown pillars of the beech trunks. The graves under its flagstone floor suggest it was built for plague victims, living in quarantine away from the surrounding villages and towns. Today it remains one of a handful of UK churches not linked into the road network, its fortnightly congregation arriving along footpaths above the noisy sea and under the tall trees.

On this first part of the Somerset Coast Path, you don't see the sea so much as smell it from sunken tracks, with salt air seeping through the head high gorse bushes. And you continue not to see the sea as the track plunges ... "down the green hill, athwart a cedarn cover!"

For we are now just 26 miles from Nether Stowey. By Coleridge standards, 26 miles was a day's-worth of walking for when he wasn't feeling particularly fit and lively. In October 1797 he was suffering from dysentery, and this may have been slowing him down a bit. So he broke his journey at Ash Farm, just above this wooded hollow. (Coleridge does not name the farm, but only Ash Farm looks down into Culbone Combe.) To combat the dysentery he took two grains of opium, sank into a reverie, and the result was 'Kubla Khan'. It may sound exotic with its dome of ice and its incense-bearing trees: but it's a long-distance walking poem, and its 'deep romantic chasm' is right here above the sea in Somerset.

All along the coast path, Coleridge's companions struggled to keep up with his continuous conversation: "His voice sounded high as we passed through echoing grove, by fairy stream or waterfall, gleaming in the summer moonlight!" At the same time they struggled to keep up with his walking, occasionally having to break into a trot to match his pace.

The 4mph stride of the 18th century, used by those who went 20 miles to any interesting sermon, or street-market, or just to visit a friend – this in our age of trains and motor cars is largely lost. If it resembled today's minority discipline of race-walking, then it involved a thrusting forward not just of the foot but of the hip as well. Along the coast path I and those around me achieved the same 4mph in the style of Coleridge's less competent companions, jog-trotting the level sections and stretching into a run on the descents.

The poets used the normal roads of commerce in their 'very long country walks in the Romantic manner' (the phrase is of Rosalind Vallence, an editor of Hazlitt). Those roads are now mostly under tarmac. But the poetic paths across the Quantocks are still here as green ways for horse riders. The Somerset coastal footpath, built in the 18th Century for the coastguard patrols against the Somerset smugglers, remains path today, though elevated to the status of a National Trail. So Coleridge's 37-mile challenge walk can be equally enjoyed two centuries later, even if modern lightweight footwear makes it slightly less challenging.

Let Hazlitt describe it for us.

"We had a long day's march—(our feet kept time to Coleridge's tongue)… we walked for miles and miles on dark brown heaths overlooking the [Bristol] Channel, with the Welsh hills beyond, and at times descended into little sheltered valleys close by the sea-side, with a smuggler's face scowling by us, and then had to ascend conical hills with a path winding up through a coppice to a barren top, like a monk's shaven crown."

It’s the Twenty-first Century, and Lynton’s Promenade is pink and yellow with bedding plants. A buzzard drifts overhead as we climb steep streets to Lynmouth and our third checkpoint. Out on the bay a rocket maroon alerts dingy sailors to the turning of the tide.

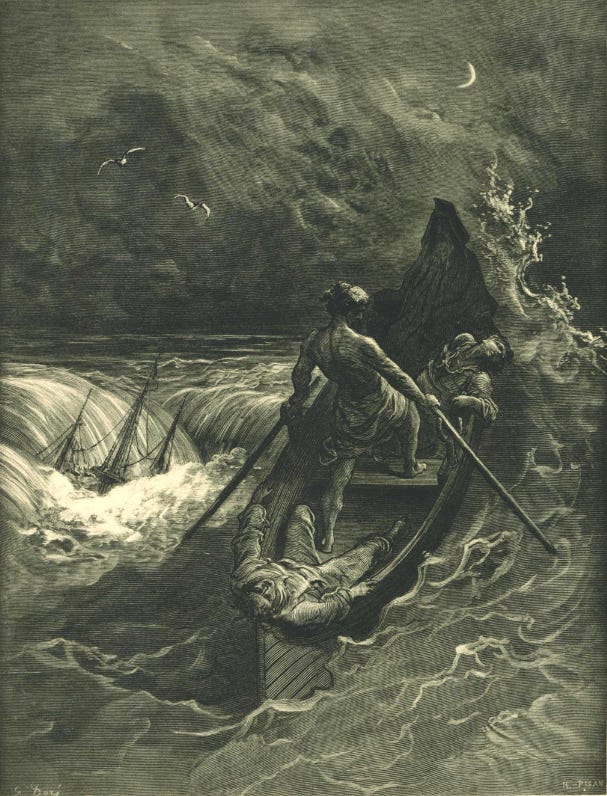

Back in 1798, with the Lyrical Ballads, Romanticism hit England with the suddenness of the flash flood that in 1952 carried away half the houses of this village of Lynmouth.The book was a collaboration between the two friends. The first half was poems by William. 'Kubla Khan' didn’t get past the cut – STC was still thinking he was going to ‘finish’ it. (Leave it, Sam: just great as it is!) But the second half consisted of another, even greater, poem of English long-distance walking – the Rime of the Ancient Mariner.

You thought ‘Ancient Mariner’ was a poem about the sea?

'Water, water everywhere, nor any drop to drink' – the thirst Coleridge actually experienced was on a walking tour of Snowdonia. He knew the sea from books, and from a single crossing of the Severn on the Chepstow Ferry on that same walk to Snowdon. The poem itself was roughed out in the course of a four-day walk with the Wordsworths: a walk whose fine natural route of seaside, woodland and Exmoor would be recapitulated, two centuries later, by me and the LDWA.

And so, in Part the Fifth of the poem, the oakwoods of Quantock make a striking guest appearance as the good spirits bear the ship homewards:

... yet still the sails made on

A pleasant noise till noon,

A noise like of a hidden brook

In the leafy month of June

That to the sleeping woods all night

Singeth a quiet tune.

Through the fading afternoon (this in 2004, but maybe also in 1797) the heat made blue haze in the winding hollows around the moor. On top, grasses were brightening from the beige of winter to the first spring green. Above what must have once been a moorland pool, a burst of sphagnum in pixie green belied the black peat lurking below.

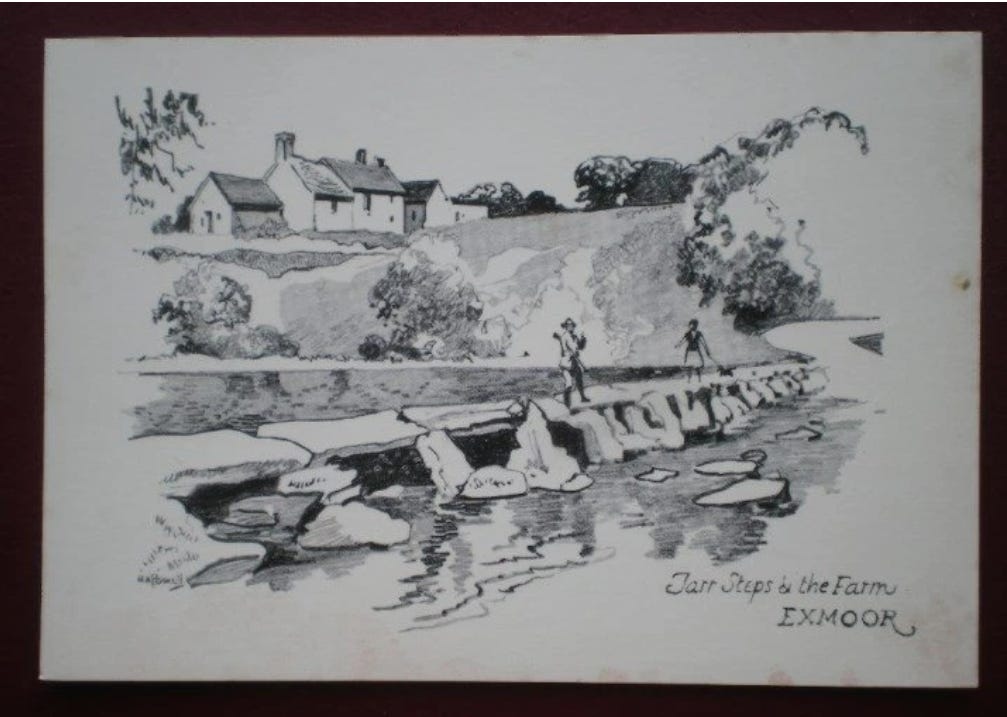

Low evening sun turned the water of the River Barle into polished metal, and the green of the surrounding slopes seemed, also, shiny and artificial, as if sprayed on. Tiredness – we'd now covered 40 miles in not much more than 10 hours – disables the brain, sharpens the senses, and turns evening Exmoor into an opium dream. Then the sun dropped behind the beech trees, and the world turned to shadow, and to night. Torches moved through the wood, and across the ancient stone-slab bridge at Tarr Steps.

How ancient? Bronze Age trackways converge onto this point, which makes this bridge with its 17 stone slabs arguably the oldest in Europe. But the argument isn't convincing. Every time it floods, the bridge gets washed away. The Highways Department has numbered the stones to help them put it back together.

Anyway, there's a better story that has the Tarr Steps not Bronze Age, but bronzage (a pun that may be considered authentically devilish). Satan, it seems, enjoyed the Barle-side picnic spots as much as the rest of us, but found them rather shady; so he built the stone bridge for sunbathing on.

It was inconvenient to have the Prince of Darkness lounging on the footbridge with his bottle of Factor Five, so they sent for the curate. Satan saw the curate off with frightful curses, so then they sent the vicar. The vicar matched him swear-word for swear-word, and Satan was so impressed that he's let us humans use his bridge ever since.

The secondary school at Dulverton had turned into any place where travellers pass in the dark. A motorway service station, say, when the overnight coach pulls in and the passengers huddle in a corner of an unheated cafeteria that smells of cold chip pans. Shadows, and plastic sheeting on the floor, and footfalls faded down a distant corridor. I sat on a bench sized for infants, washed and repaired my feet; I put on fresh socks from the small, marked bag that the walk organisers had carried forward for me.

I left Dulverton below the stone house-fronts and narrow windows passed by Coleridge and the Wordsworths two centuries before, their brains seething with the sea, icebergs of the southern ocean, and a ship of bare hollow timbers where death played at dice.

English Romanticism. It's a turbulent world of the emotions, expressed in paint, in music, and in the written word. It involved experiments in communal lifestyle, and experiments with laughing gas and laudanum. But it also, in a fundamental way, involved fell walking.

Gothic novelist Ann Radcliff up Skiddaw, Samuel Taylor Coleridge rock-climbing down Scafell. The Shelleys off across Europe to inspect Mont Blanc; Keats walking all the way to Fort William to climb up Ben Nevis, specifically as part of his training into being a poet. Byron wrote verses in praise of Lochnagar, although he didn’t actually climb up it because he was born lame with a club foot. But when his romantic hero Manfred needed to end it all, he couldn’t come up with a better way to do it than climbing up the Jungfrau in order to throw himself over the edge.Romantic verse may be terribly out of date. But the four hundred of us walking through Dulverton in the dark are, all of us, pursuing the agenda of Wordsworth and Coleridge. As I came up out of the yellow streetlight, the black of the sky was streaked with grey. My way led into an ancient hollowed path; and the dark branches all around were full of birdsong.

If that's not English Romanticism I don't know what is.

You swine Turnball - i had to look up the meaning of bronzage - thats another word just dropped out of the other side of my brain.

Another good piece.

Never too sure how the mix of soporific drugs and long distance walking ever meant the Romantics managed to get anywhere at all...or perhaps it was all a dream

A fine tale, well told, but dashing around the countryside has never been my scene. Why the hurry? Too much to see and maybe hear - and on that coast never too far to get to a sea cliff for adventures on rock.