My neighbour Joseph Thomson explores the Atlas

Joseph Thomson, stonemason’s son from Dumfriesshire, was the fourth most famous African explorer, and the earliest European adventurer in the Atlas Mountains of Morocco. [1300 words 6 mins

This week I celebrate my neighbour Joseph Thomson, one of the world’s great long-distance walkers. Thomson was a stonemason's son from my village here in middle Nithsdale who became the most famous African explorer you haven't heard of. Specifically, you know about Livingstone, Stanley, and Mungo Park. My neighbour is the next most famous after them.

Thomson walked from Zanzibar to Kilimanjaro and then to Mount Kenya. He walked across South Africa. Between 1879 and 1895 he walked 15,000 miles in Africa, picked up at least four tropical diseases, and gave his name to a waterfall and a gazelle, two land snails, and a freshwater bivalve from Lake Tanganyika.

Scotland has a tradition of the ‘Lad o’ Pairts’ – a young man from the working classes who manages to educate himself and move out into the world. Robert Burns, of course, and his fellow-shepherd James Hogg; Thomas Telford, son of a Langholm milkmaid who became the foremost engineer of his age; Victorian philosopher and historian Thomas Carlyle, who was a stonemason’s son from Ecclefechan.1

Scotland after the ‘Edinburgh Enlightenment’ of the 18th Century did have a certain egalitarianism. Add to that a respect for education, in all social classes, which brought the world’s second-ever public lending library to the lead-miners of Wanlockhead.2 And there’s a chance for a young, working-class boy, given luck, hard work, and a helpful local patron, to take his place among the Edinburgh intellectuals.3

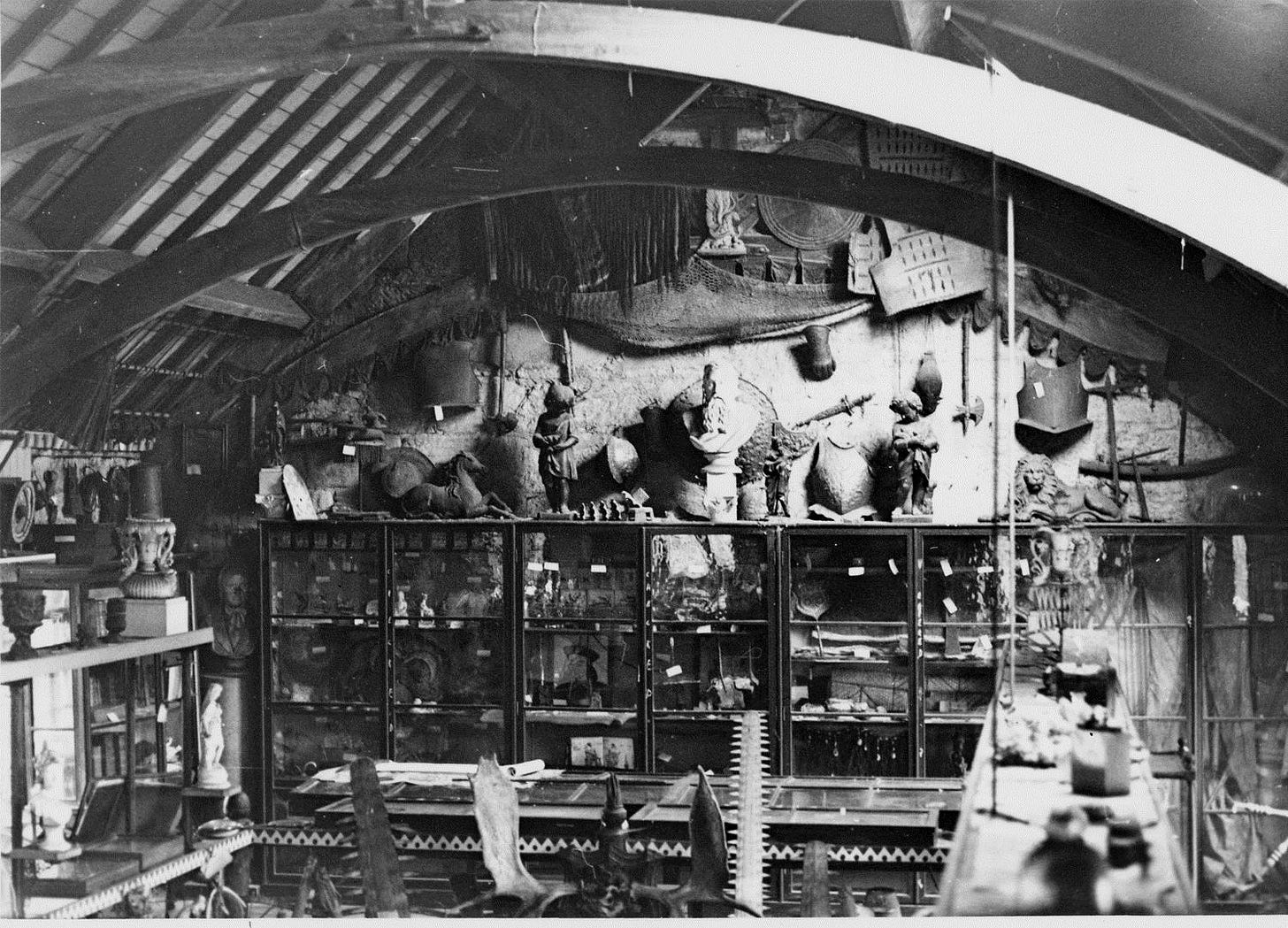

Dr Grierson’s Museum in the village of Thornhill. Thomson later donated some ostrich eggs.

For Joe Thomson the patronage came from the local GP, Dr Thomas Grierson, who for his own amusement and the improvement of his village built a middle-sized museum on a plot of land kindly granted by the local duke and former warlord Scott of Buccleuch.4 And the luck came while hunting Carboniferous ferns in a little local gorge, where he made friends with the Edinburgh professor and leading geologist of his time, Archibald Geikie.

But his long distance walking exploits were all his own.

A dose of salts and a shock from the battery

A generation earlier, the third most famous African explorer had been Mungo Park, a tenant-farmer’s son from Selkirk in the Borders.5 Fired up by Mungo’s exciting writings, Joe Thomson got the gig as geologist on an 1878 expedition through the Maasai lands of East Africa. Within a couple of months the expedition leader died, leaving the 20-year-old Thomson in charge as sole surviving European.

Thomson's proudest boast was that he walked those 15,000 miles through Africa without ever having to kill anybody at all (except, in the end, himself). When he needed to make an impression on a Maasai chieftain, he would administer a dose of Eno's fruit salts and a shock from the galvanic battery. If that failed, he’d take his false teeth out and put them in again.

In between expeditions, he walked across Southern Scotland. One of his 70-mile training exercises took him from his family home across the Southern Uplands to Edinburgh. In a single day. He walked that one in July of 1886, stopping at Biggar for breakfast and reaching Edinburgh in the early evening.

Their faces were a sight

After 10 years of exploration in East Africa, South Africa and Nigeria, my neighbour had become somewhat disillusioned with the colonial project, speaking out in particular against the socially destructive trade in gin and guns. This meant that his funding dried up. His next trip would be self-financed, motivated only by exploration and adventure. And so, in 1888, he wrote his will and set off to the Atlas Mountains of Morocco: according to the naturalist Sir Joseph Hooker ‘the most difficult of all countries to explore’ because of the stony going, bad maps, and extremely hostile locals. “Once more it is my fate to move on, driven by a resistless demon within me—a species of Frankenstein which I have called into existence and cannot now get rid of.”6

On this one, unusually, Thomson travelled with a European companion, 22-year-old Mr Harold Crichton-Browne of the British Army. In his book Thomson shows real compassion for young Crichton-Brown when he fails altogether to enjoy 14-hour days through rough unexplored country while being pursued by armed Berbers.

As well as Crichton-Browne and a military ‘guide’ or minder helpfully supplied by the Sultan, his company included 5 mules, a camel, a donkey and a horse. Along with the associated muleteers, who “never ceased to thwart, by every means in their power, all my attempts to go to the mountains.”7

A later Gatelawbridge resident on southern slope of Toubkal

They got through by waving an important letter from the Sultan Mulay al-Hasan of Morocco. What the letter actually said was that they were to stay on the main roads and on no account to enter the mountains. At the same time they had to deceive their mutinous muleteers. "It was only when we were well into the mountains that the situation dawned on them – and then their faces were a sight to see."

“In defiance of dogged official obstruction, and despite the never failing knavery of his men, the fanaticism of the inhabitants, and the risk of death itself which hovered about him everywhere,” he reached the main east-west watershed at seven points, and mapped several unknown valleys.

Thomson correctly identified the mountain forms as being caused by previous glaciation. Poor young Crichton-Brown got bitten by scorpion and retired from the expedition. Berber tribesmen with guns then chased the party up Jebel Ogdimt (now known as Jebel Igdat, 3616m), the highest point of the western Atlas.

Gradually dropping his assailants, however, scaling difficulty after difficulty, and passing through the zone of clouds itself, so that he could look athwart their upper surface as upon a vast white sea in which the mountain peaks shot up as islands, he at last stood upon the sky-piercing summit exhausted but triumphant, and measured it at 12,734ft [3881m, about 250m too high].

Photo taken in Largs, Ayrshire: so the ‘Arab’ background is presumably someone’s kitchen range in Scotland

Taking a short break in Marrakech, he visited tourist sights disguised as an Arab, including mosques, the public baths, the dancing girls and even a harem. He was almost stoned to death by an irritated mob, but managed to defend himself with his horsewhip.

124 years later, my son Tom and I became only the second and third persons from Gatelawbridge to cross the high pass called Tizi Likemt (3555m). Compared to our neighbour Joe, our trials were very mild: a full set of kit lost at the airport, and an elderly mule that failed to make it up the 1500m of ascent from Tacheddirt. “Standing finally at an altitude of 13,150 feet [actually 11,650ft] among wreaths of snow, he gazed upon a scene of indescribable sublimity, a bewildering, awe-inspiring assemblage of snow-streaked elevations, sharp jagged ridges, and deep glens and gorges.” From the pass, he was able to observe Toubkal 12km away to the west and establish it as the high point of the range.

The tropical diseases got Joe Thomson in the end: he died in 1895 at the age of 37.

Tizi Likemt is now part of a standard Round Toubkal Trek

I have to admit, though, that not all of these worthies emanated from Dumfriesshire. Robert Burns merely moved here in later life from across the Ayrshire border.

July 1788, and also in Dumfriesshire, by the way. The world’s oldest one, from 1741, being at Leadhills 1 1/2 miles away across the Lanarkshire border.

No such oportunities for working-class girls, needless to say – no ‘lassies o’ pairts’.

The Buccleuchs made their pile by successful cattle thieving in the sixteenth century, but that’s another story. By the 19th Century their estates were wide enough that the Duke was also patron to Mungo Park, 60 miles away across the mountains.

Okay, it’s outside Dumfriesshire by a good 20 miles.

He means Frankenstein’s Monster, of course: the monster itself being addicted to mountain travel on the glaciers of Mont Blanc and an early crossing of the Arctic.

All quotations are from ‘Joseph Thomson, African Explorer’ by his brother, Rev. JB Thomson, 1896: a hugely popular book which went through several editions

Thanks for your helpful post about Joseph Thomson, his often quoted saying is that he who goes quietly goes safely, and he who goes safely goes far.