Magnificent new maps

My hillwalking map. It’s a faithful companion, and can’t possibly be improved. Until, quite unexpectedly, it can. [1000 words 4 mins

I’m not a connoisseur of outdoor kit. Ambleside, with its compelling rows of gear shops and outdoor emporia, leaves me cold – and not just in the sense of not being enveloped in the latest down-filled puffy trousers.

But now and occasionally, in my life on the hills, there comes along an innovation that I’ve been entirely happy not needing to have – and almost at once, can’t believe I ever managed without.

This happened, indeed it did, with fleece clothing. Wooly jumpers: okay, they got rather heavy when wet, and really did absorb an awful lot of water, and wasn’t it his wooly jumper when it got caught in his karabiner that led to Tom Patey’s fatal fall off that seastack? But if it’s good enough for a sheep, let alone Tom Patey, then it’s altogether adequate for the likes of me.

Again, a few years after that: waterproof trousers. Legs get wet, legs get dry again: this seemed entirely satisfactory. And crampons? On Scotland’s icy gullies? Whatever’s wrong with the noble art of stepcutting with the axe?

But most noticeably of all – because it’s come about, in the history of hillwalking, six separate times over: is the matter of maps.

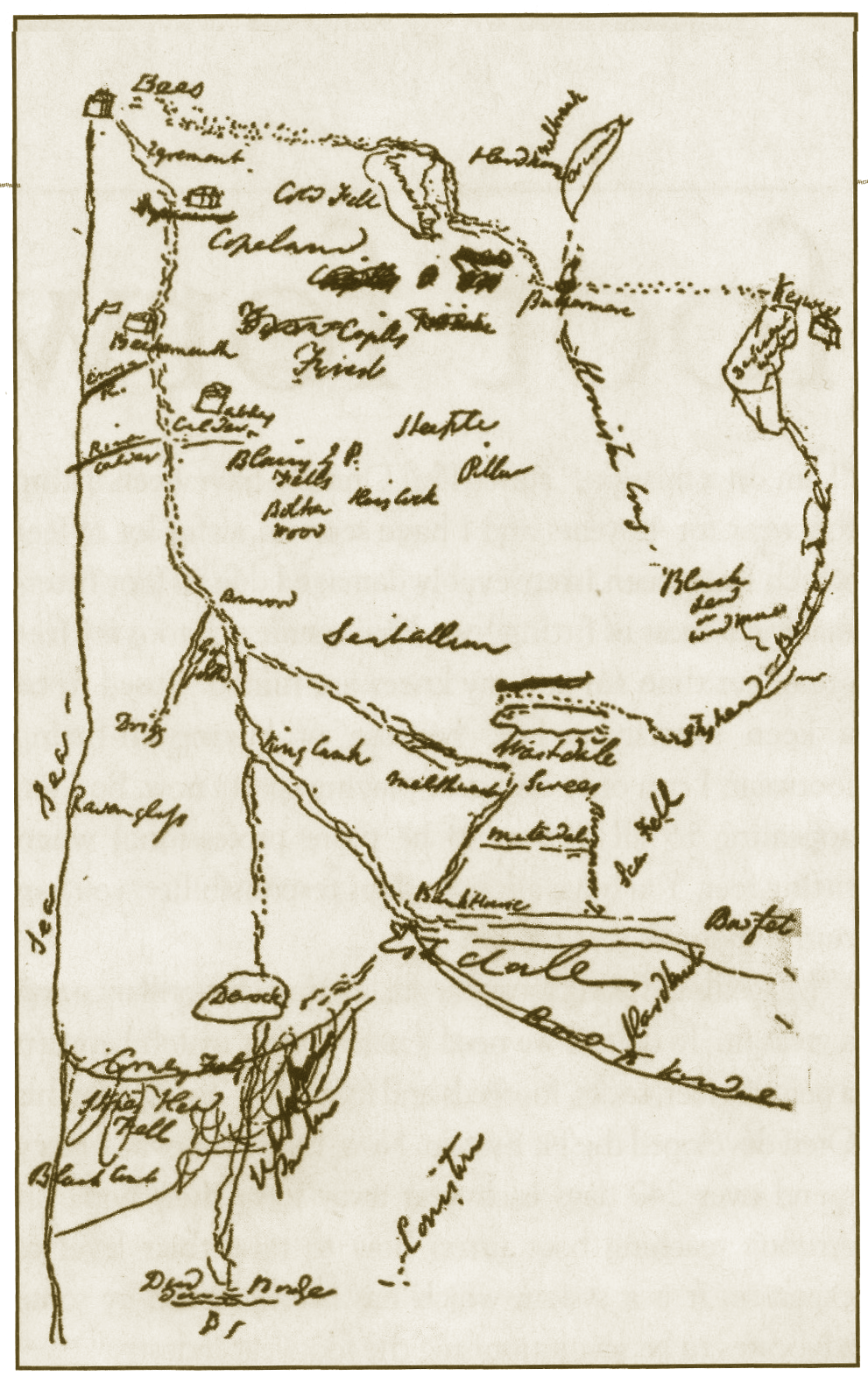

Coleridge and his sketch map

When the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge was planning his nine-day hike around the Lake District, he had to make the map himself. Which wasn’t a problem. There were people right there in Keswick who knew the way across to Wasdale: he collated all their information and sketched it together in his notebook.

Okay, so he got Ennerdale and Wasdale the wrong way around. Which didn’t matter much; finding the way was part of the fun of it, and the shepherd at the top of Eskdale could tell him how to get over into Duddon. And yes, he did lose half a day on the Dunnerdale heights, ending up back where he started off. So what? He was having a grand time of it all the same.

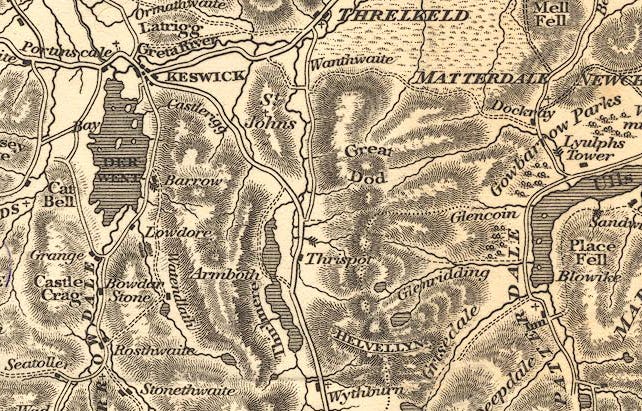

Jonathan Otley’s magnificent new map

But then in 1818 came Mr. Jonathan Otley, clockmaker of Keswick. Not the first to make a Lakeland map: but Jonathan was a trained surveyor, and also had a portable barometer for measuring heights with.

And he produced absolutely the last word in maps. I mean, it had everything on it: all seven radiating dales in exactly the right order. It even clarified which was which out of Sca Fell and Scafell Pikes.

Which, was this even a good idea? With farm incomes falling all the time, the shepherds of the various valleys were supplementing their income with sixpences and shillings from guiding the influx of new tourists from the cities. If it was too easy for those tourists to find out where Great Gable was, then this might have serious economic consequences.

Whatever, this map has it all Every single hill – what more could any of us possibly want for finding your way among the Lakes?

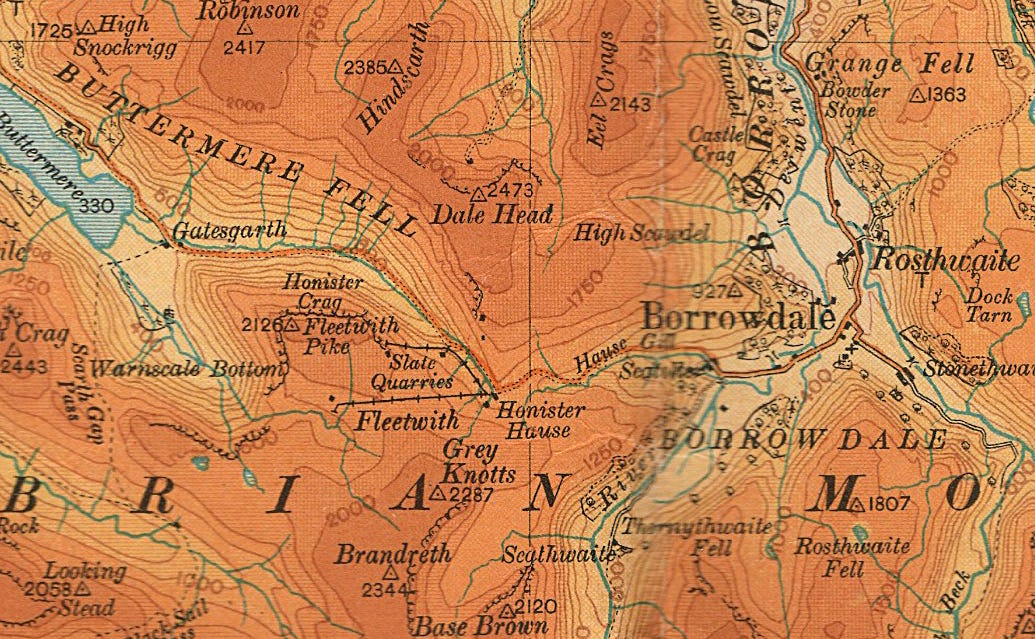

Bartholomew’s with the contour lines.

Meanwhile, away up in the Scottish Highlands on a hill called Schiehallion, a mathematician called Charles Hutton is busily inventing the contour line.

And Otley is obsolete. Actually having the shapes of the hills, right there where you could see them on the map in your hand. And colour shading to help indicate the heights as well as looking so richly greeny-brown. And those cool contour lines, every 250ft you go up. And spot heights! We never asked for spot heights, but they’re so handy aren’t they?

Here’s a bit ofmy Grandpa’s map that guided all his climbs and fellwalking through a lifetime of the Lake District. No more wandering down the wrong side of Esk Hause and ending up at the Woolpack Inn. With a compass and a bit of attention to where you’ve got to, no need to get lost again, ever.

Sometimes, you can even still find the way when the cloud comes down.

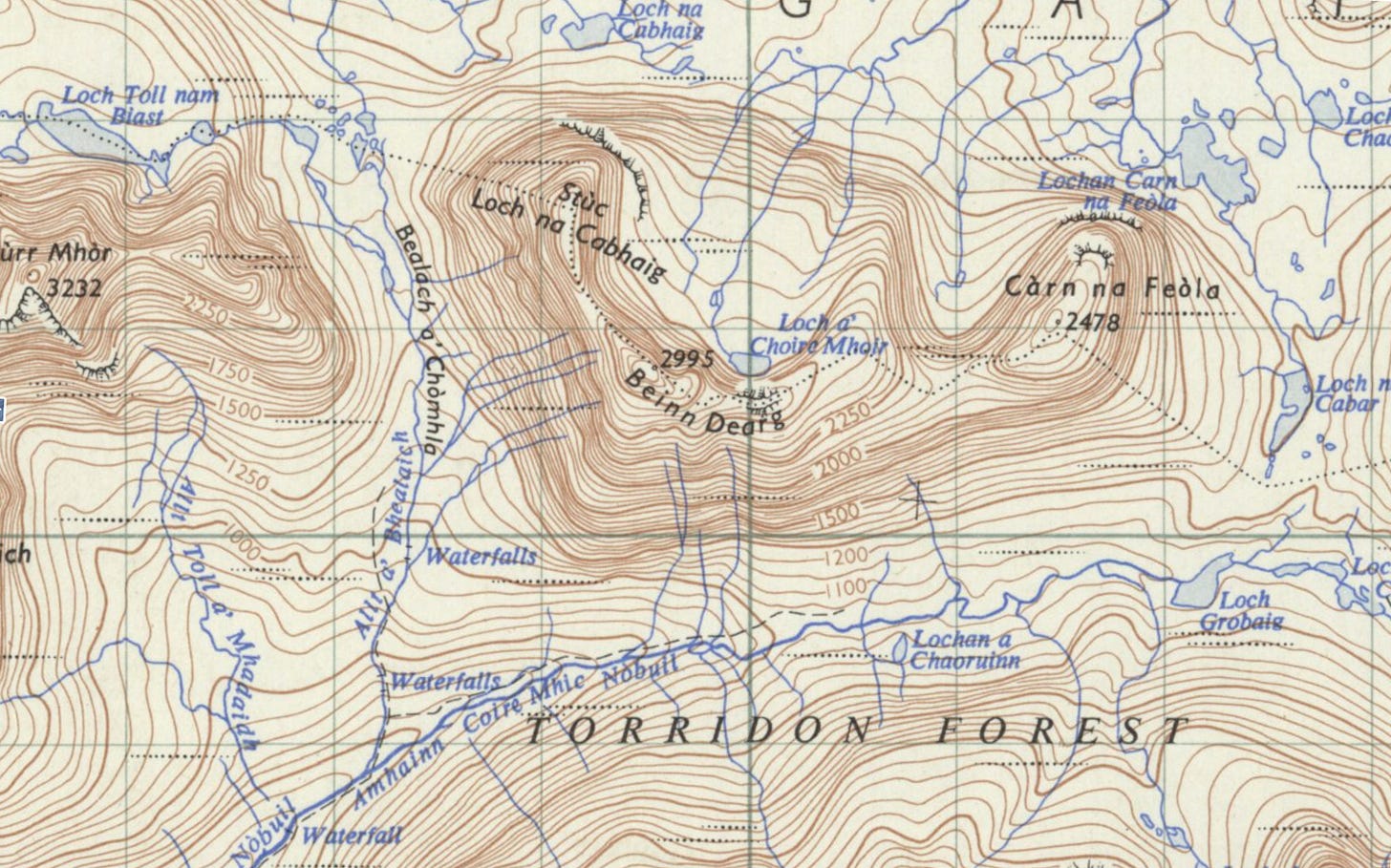

One-inch from the Ordnance Survey

And then, in the years between the wars…. And now, honestly, this is not just the best map there’s been so far, but, in all essentials, the best map there could ever be. Superb clarity, enormous one-inch-to-the-mile scale, those useful National Grid markings even if they are in those foreign kilometre things, a precision contour interval of just 50 feet, a soothing blue and brown colour scheme and classic Gill Sans italic fonts.

And if the big hills of Wester Ross, all shrouded in their rainclouds, haven’t been entirely surveyed yet – those big flat ridgetops on Beinn Dearg, not in any way resembling the real-life mountain… It all just helps keep us alert and paying attention. We need at least a little bit of original exploration in our lives, no?

Harveys

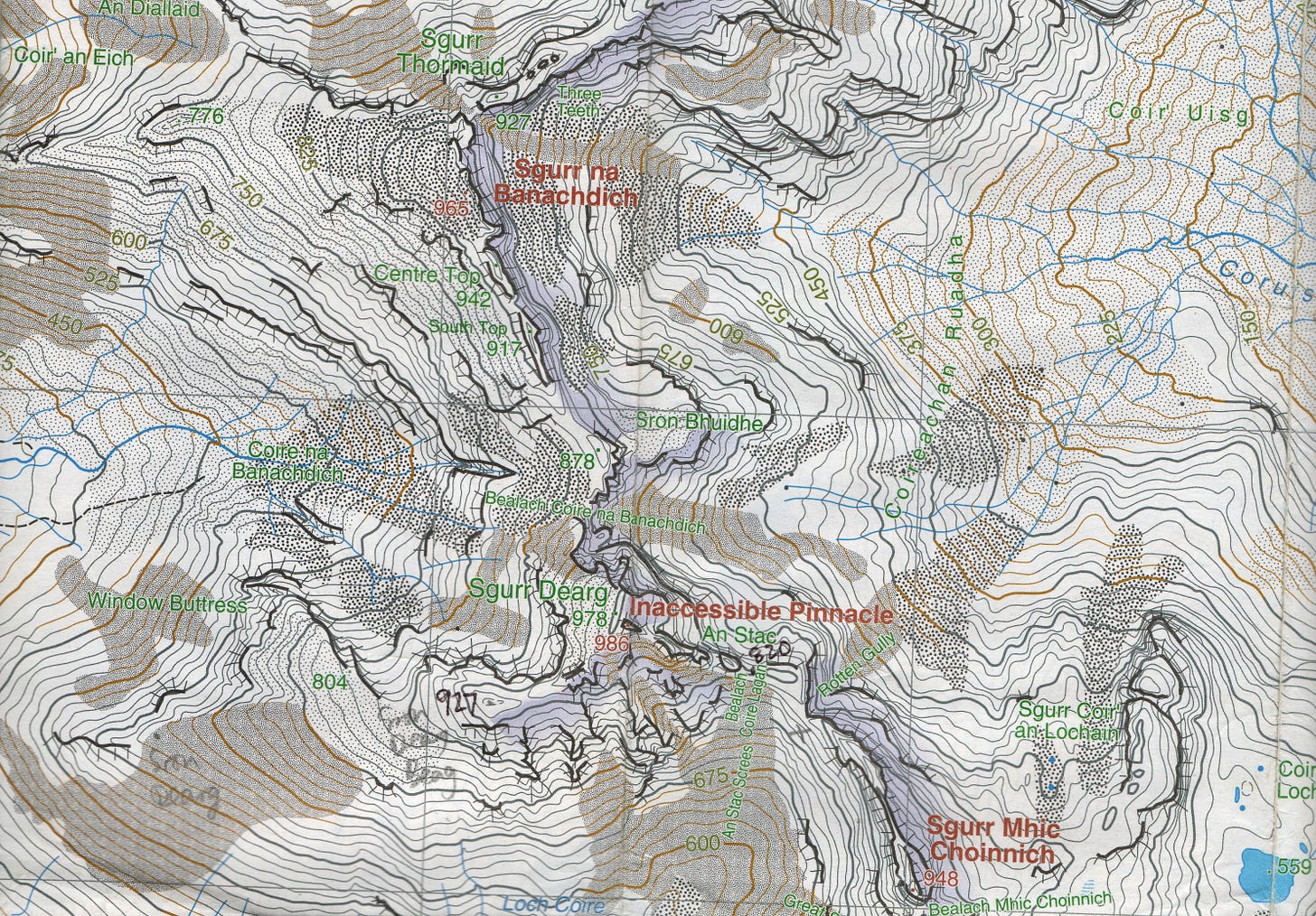

And then, some time in the 1960s, the Cuillin of Sky lose much of their mystery. Alas: it’s the end of the one place in the UK where you could wander as lost as you liked, without any clue at all as to where you might be up there or which of the spurlines descending into the mist might represent the continuation of the fabled Main Ridge.

A Harvey map, with its intimate contour detail, all clear enough you could even read it in the rain, even read it without your glasses: what more could we possibly desire?

Outdooractive and other apps

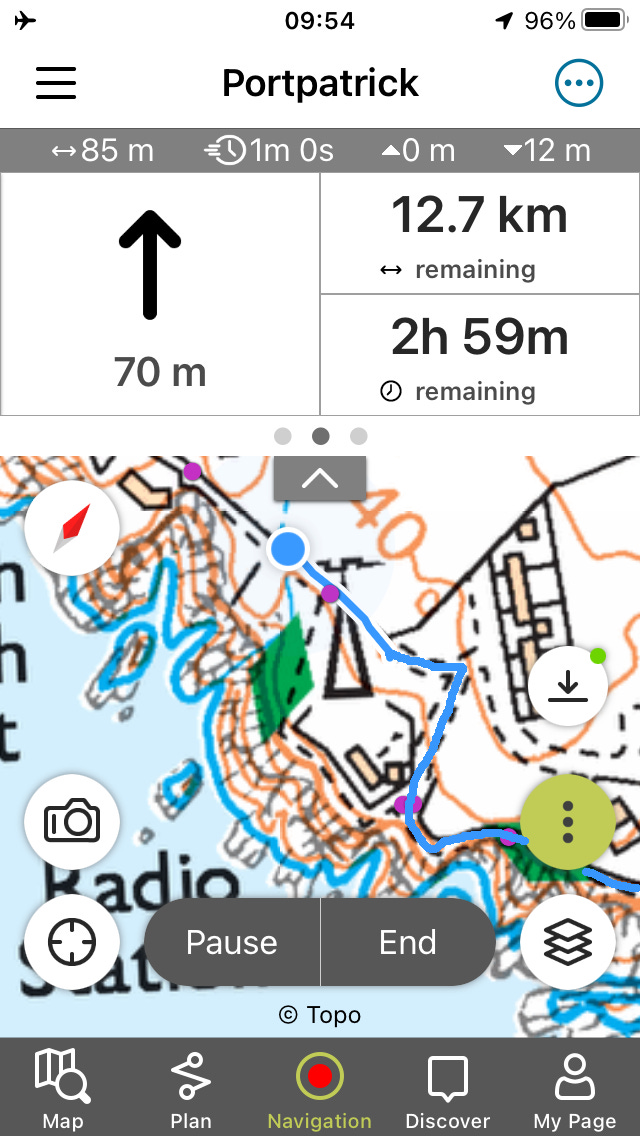

Well, perhaps we’d like a map that actually shows on it our current position, using a little blue dot, that would be tasteful? Obviously impossible – except, sometime around 2010, it went from impossible to obligatory.

Obligatory for some, at least. Not for us map and compass men and women.

Which, any road, just has to be the end of the line so far as mapping and routefinding goes. Your map not only knows the exact shape of the surroundings, and pinpoints exactly where you are in it. It’ll even tell you which way to turn, and give a little beep if you’re more than 10m off your route. Ten years ago, never knew we needed it. Ten years from now: criminally irresponsible to be using anything else. But from here on out, no further improvements can be imagined.

Well, you know: that’s exactly what they were saying back in 1821 about Jonathan Otley’s magnificent new map.

So what do you think? Is your map or app cleverer than you are yourself? Will future phones do the walking for you so you don’t even have to get wet?

I enjoyed this hugely. My wife and I have used the ordnance survey app for many years now. In the benign Welsh Marches it is great. The consequence of failure is minor. No cliffs to fall off if the weather comes in, no Grimpen Mire to be swallowed by. Nonetheless, we always have a power pack and lead in case one gets delayed and battery runs out. If we were going up to Snowdonia we would ensure we had a paper copy… just as we have other safety kit.

Years ago i dived in Malaysia. I always had a klaxon in BCD airline. Less experienced divers would ask ‘do I need one of those’. Maybe, I would reply. And I did. I dived with an instructor. It seemed benign but as we went down we realised a huge current was running along the bottom. We tried to get behind the shelter of a coral (that works, like a rock in a gale). But we couldn’t make it and we abandoned the dive. We did our safety stop and when we surfaced we were half a mile from the boat. The instructor put up a marker but the boat failed to respond. I blasted. It took three goes. A few days later two divers were in the sea two days because the boat couldn’t find them.

So we take care walking, but we use an app all the time and it’s brilliant.

A little note on ice-steps. My son climbed a 6000m summit in the summer. Last 300m 45 degrees took 3 hours in crampons, hammering in breathes with every step. I bet he was glad not to cut steps!

I'm so glad I came across this wonderful read! Little did I know, as an elementary school student visiting the USGS headquarters on our annual field trips there, that I’d one day be working in the world of maps and mapping apps once I moved to the UK. I’ll admit I’m heavily biased toward Harvey Maps, possibly as they feel most familiar in style to the USGS maps, though I would argue Harvey's are far superior!