I took a walk in the woods and came out taller than the trees. - Henry David Thoreau

"I see that skinny trail heading in under the trees," says the lady from Pensylvania, "and it's just so pretty, I want to head in and do it all!"

All of it is 1000-odd miles of the Mountains to the Sea Trail in North Carolina. 1000 miles means a heck of a lot of trees. But that's cool, North Carolinans like trees. One of them went visiting in England and at last they took him to Snowdonia – but before they got to Snowdon itself, they passed the foothills with the forestry plantations. "I was clawing at the car windows," he told me. "I just wanted to get in under those trees."

As a non-Carolinan, five days of Mountains to the Sea would do me. In the course of those five days, I would be passing approximately one million trees. Once each day, or even oftener, I'd emerge to a hilltop clearing, and see a view. That view would be a view of trees.

Once, there wasn't any First World and Third World. There wasn't even Town and Country. There was the cleared ground: and there was the forest. At the edge of the field, the green wall rose to close off the sky, stony soil gave way to reddish mud or peaty swamp. Push through the low branches, a bent arm protecting your eyes, into a place of dim light and toadstools. Movement is struggle, no direction is different from any other, and anyone who lives out here would just as soon you were dead as not.

Roman roads were extensions of the clearing, with the forest cut back for the width of two bowshots on either side. That still left a world that, north of the Alps, was mostly oak trees. In AD9, the XVII, XVIII and XIX Legions under Varus marched in under those trees and was never seen again.

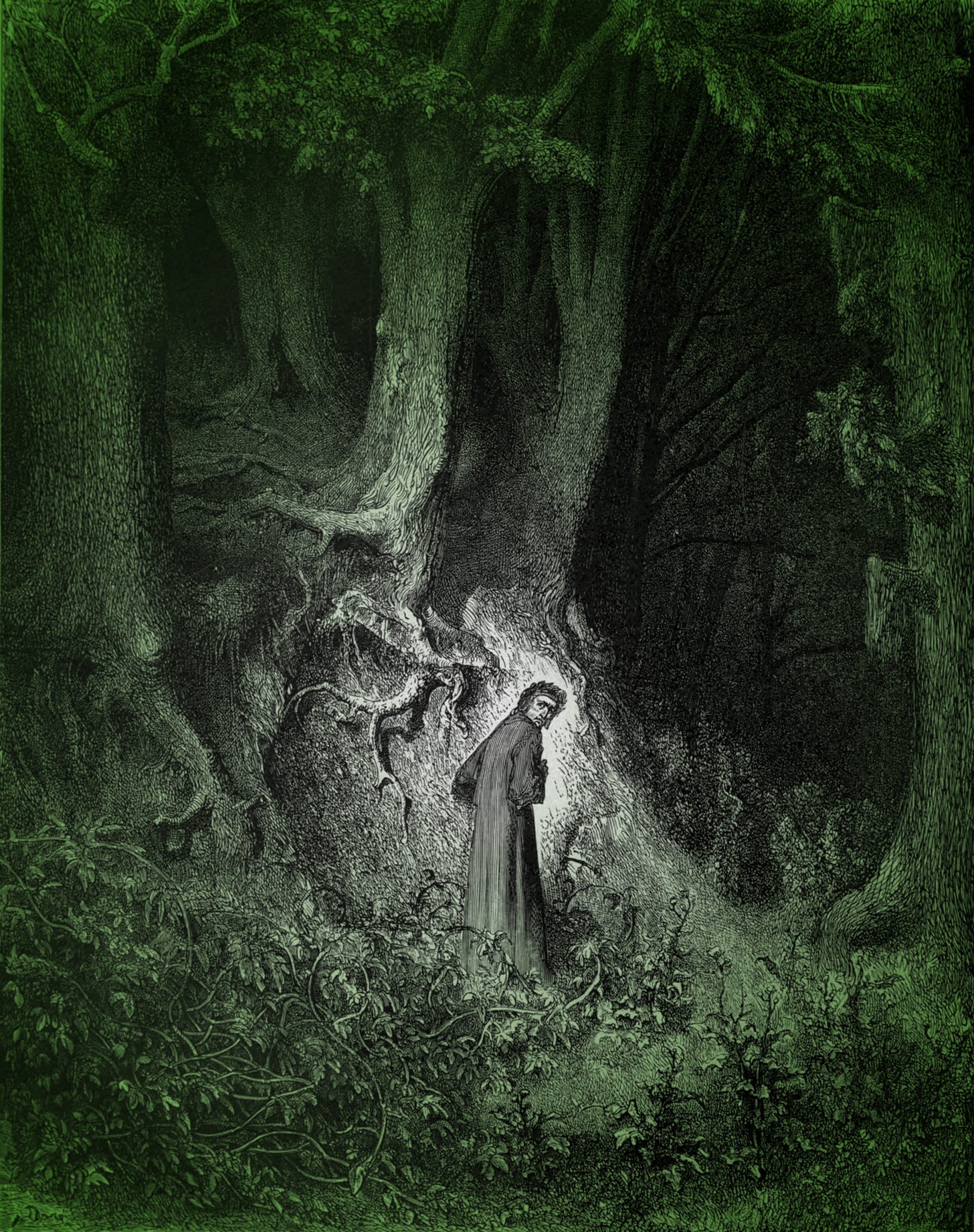

Sir Gawain, the moment he left the gates of Arthur’s stronghold, the forest closed in around him: the Green Knight himself, with his sinister self-regenerating neck-bones, a symbol of the fear that lurks between the leaves. For Dante, the woods were the bad place you ended up in if you lost your way.

Nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita

mi ritrovai per una selva oscura

ché la diritta via era smarrita.Half way along the journey of our life, I found myself within a darkling wood, where any forward path was gone astray. Inferno, opening lines

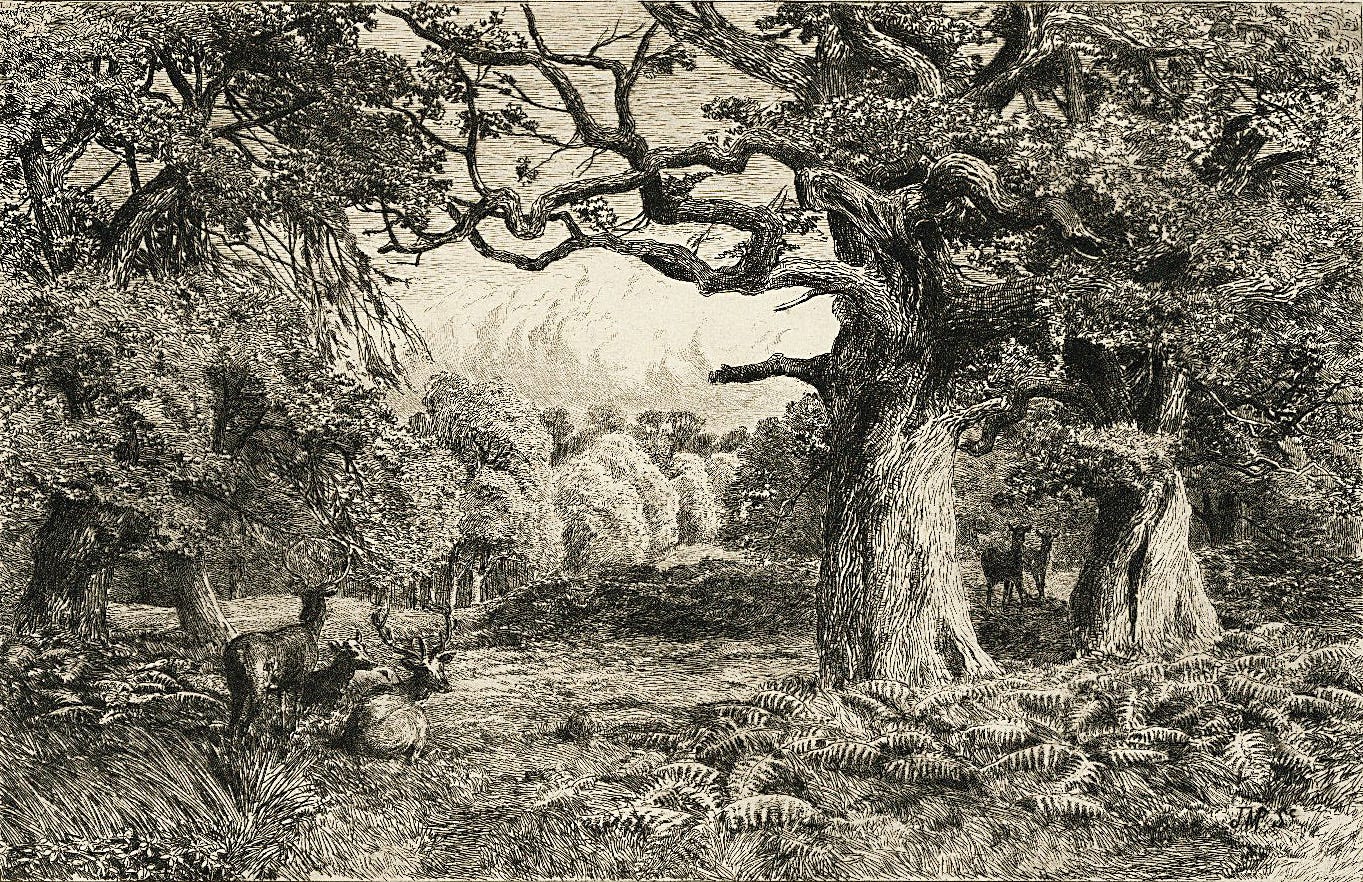

But by this time the wild woodland had ceased to be the default state of England. Like the difference between an aerosol (gas with drops of liquid in it) and a foam (liquid with bubbles of gas) it was the open pasture that had become the continuous phase. There was no longer 'the wood' but just 'woods', individual patches with edges. And no longer the default condition of the hostile world, no longer an obstruction to travellers, a wood became a place.

And almost at once, that place was a pretty place. It was the Forest of Arden, where you fled to get away from the murderous intrigues of Count Frederick:

And this our life, exempt from public haunt,

Finds tongues in trees, books in the running brooks,

Sermons in stones, and good in everything.Shakespeare, As You Like It, II, i

Vegetable Love

Milton's Paradise was a wooded one; and influenced garden design for a century after its publication.

" Cedar, and pine, and fir, and branching palm,

A sylvan scene, and as the ranks ascend

Shade above shade, a woody theatre

Of stateliest view…And all amid them stood the Tree of Life,

High eminent, blooming ambrosial fruit

Of vegetable goldMilton, Paradise Lost (bk. IV, l. 139)

'Vegetable' here means 'growing in the style of a plant'. This arcane usage, from the Latin vegetare, to grow,

Our vegetable love would grow

Vaster than oceans, and more slow…Andrew Marvell ‘To his Coy Mistress’

But Marvell, I think, is gently mocking his poet colleague, as he imagines this unconsummated love as a giant cabbage, all leaves and no fruit, swelling across the continent. Marvell's sensuous poem, now probably his most popular, was unpublished during his life, so we can't say for sure that it was written after, and in gentle mockery of, ‘Paradise Lost’.

But Marvell too was a lover of the forest:

Meanwhile the mind, from pleasure less,

Withdraws into its happiness :

… Annihilating all that's made

To a green thought in a green shade.Andrew Marvell ‘The Garden’ 1681 (https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44682/the-garden-56d223dec2ced)

Milton was the Puritan, and Oliver Cromwell's personal secretary for his correspondence in Latin. Marvell, despite religious differences, was Milton’s assistant and friend. And it was during the terrible Civil War, during which one in three Englishmen was wounded or killed, that their minds and feet strayed to the green shelter of the Paradisal forest.

Sir Peter Lely was the court portraitist who lived through the Civil War. The one who painted Oliver Cromwell 'warts and all'. But the portraits were just hackwork where he painted the face and let his assistants paint in the rest from a shortlist of prenumbered poses. Because what he preferred to be painting was trees: wooded Arcadian landscapes with nymphs and shepherds and no blooming Oliver Cromwell anywhere to be seen.

Sir Peter Lely ‘Nymphs by a Fountain’ (Dulwich Picture Gallery) 1650. The hairstyles and discarded clothes are contemporary, making it sexier.

There is a pleasure in the pathless woods – Byron

Two hundred years later, on a different continent from Milton, in a different conflict, President Lincoln turned his attention away from the War Between the States, towards the big trees of Yosemite. So that on June 30, 1864, even while his armies were unsuccessfully besieging Petersburg and General Jubal Early was threatening Washington itself, President Lincoln was signing the Yosemite Grant Act to preserve Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Grove of giant sequoias for “public use, resort, and recreation”.

For the National Parks of the US would be, primarily, places all covered in trees.

I step off a pull-off of the Blue Ridge Parkway and in underneath the branches; and start looking for the white paintspot markers of the Mountains to the Sea Trail.

The spots lead downwards, through gloom where butterflies flutter. The trail is floored with brown leaves and weird non-photosynthesising plants. Treetrunks rise high; oaks with overlarge leaves, tulip-trees referred to as poplars, the occasional pine.

I make my first camp on pineneedles alongside the creek. Using tricky ropework, practised at home beforehand, I hang my two food bags over a branch in such a way that both of them are more than 10ft above the ground. Bears are not nasty. For every hiker torn to bits by a bear, a hundred die by lightning, or by bees, and two or three thousand are killed by other human beings. Alone in the forest, with the water making random noises and the tent wall less than a sixteenth of an inch thick, bears are nasty to think about, that's all.

It takes about ten minutes to get completely dark. Fireflies sparkle in the shrubbery, and when one settles on the tent it makes a green glow through the nylon. A single mosquito zings in the tent top. The overnight temperature plummets to about 60 degrees Centigrade which is far too hot for my sleeping bag.

At dawn, sunlight creeps in between the treetrunks and sparkles in the creek.

Trees? Yes, please!

Loved this one! From making me laugh to beloved Dante and Milton!

What a splendid essay! You quote with a deal of authority, some of my favorite writers, especially Marvell, whose study is probably languishing in the academy.

Trees are, after all, our oldest friends, a far more ancient association than dogs or cats and I rarely beheld a tree I did not like. But the forests can be scary, especially at night, if you travel alone in them. And that fear is ancient as well and somewhat well founded as night is the time when many predators come out to sport. The little marsupial in us remembers that well.

But everywhere we tamed the forests with criss-crossing roads, made parks of them, or worse monocultured commercial forests. So global warming was enhanced, ancient water cycles broken, fires raged, and flooding brought the trees down. All because we broke the bond, the ancient friendship. We must now sit down at a bitter banquet of consequences