Adventures in the Alpine Style

Boardman and Tasker Part 1: Joe Tasker [1400 words, 6 mins

Mountaineering, back when it started, sort of made sense. Get yourself, by whatever seems like the easiest way, to the summit point of the Zinal Rothorn or Mont Blanc or maybe the Matterhorn. But increasing skills, better equipment, well written guidebooks by those who’ve already been there: all of these start to make it all too easy. Which is when we have to devise rules, ethical systems and extra difficulties to make it all harder again.

So yes: climbing Everest with 13 lead climbers, oxygen cylinders and four and a half tons of gear hauled uphill by 362 local porters: that was impressive in 1953 – but it isn’t any more. Here, briefly, are the downsides of big-expedition climbing on the big Himalayan peaks:

1. With Sherpa guides, five or more porters per climber, and several tons of equipment, it’s very expensive (you’ll spend more time fundraising than actually on the mountain).

2. You’re part of a large bureaocratic machine, possibly led by someone not quite so competent as Chris Bonington – whereas, being a climber, you’re temperamentally something of a free spirit.

3. You almost certainly won’t be one of the small team to get to the summit (Dougal Haston has a habit of grabbing that one).

4. Almost none of your time will be spent confronting and climbing new untrodden ground.

5. By contrast, almost all of your time will be spent carrying large loads up and down fixed ropes while suffering from altitude sickness.

6. There’s an appreciable chance you’ll lose fingers, hands or feet to frostbite, or get killed falling off, or get killed by an avalanche.

The solution is simple. Don’t climb the big Himalayan peaks.1

But there’s a alternative solution. Climb the Himalayas as if they were much smaller ones somewhere in Europe. Take a small team, perhaps just two of you. Start at the bottom carrying bivvy gear, and just keep on upwards until you reach the top.

At a stroke this eliminates Downsides 1 to 5.

At the same time hugely exaggerating Downside Six…

The Alpine Style is the purest, the boldest, the most insouciant. At the same time, by any sensible criterion, it’s a total no-no.2 Between 1975 and 1982, the dream team for this kind of thing was Pete Boardman and Joe Tasker.

In the interests of working out which was which, I’ll post about the two of them separately: Pete Boardman coming in this time next week.

Joe Tasker was born in 1948, into a working-class, Roman Catholic family from Teesside – his father was a school caretaker. His adolescence was spent in a Jesuit seminary, training to be a priest. After his seven years there, the ‘Summer of Love’, must have hit him like an avalanche on Kangchenjunga…. Turn on, tune in, drop out and get high – but applying his own more literal interpretation to the last two words.

Quickly he dumped the priesthood in favour of work as a dustman, Lake District quarryman, and scavenger around climbing campsites for empty bottles to cash in for the deposit refund. But in those days student grants (subsistence and tuition) were paid by the state: allowing him to combine his climbing with a degree in Sociology at Stanage Edge (aka Manchester) University. He also trained himself as an outdoor photographer, film maker and writer.

Tasker’s writing style is simple and direct, unlike the English graduate Pete Boardman. And this fairly mundane style can deliver sudden insights like a stone falling from above… Before a winter attempt on the Eiger’s North Face:

”Naive as I was, I did not know if it was normal to worry that we might not come back”.

Dunagiri is a 7066m peak in the Indian Himalaya: not the very highest, but one of the ones that’s steep and intimidating all the way around. As a one-time minor mountaineer, I’m blown away by Joe Tasker’s 1975 trip there with Dick Renshaw.

A scruffy expedition it was, with only a tiny amount of sponsorship and an almost Hippie ethos, as they set off overland to India in broken down van.

The companion Dick Renshaw in Tasker's account comes across as taciturn, almost silent, and driven. After several very serious climbs together, Tasker admits that he still doesn’t know Dick Renshaw at all…

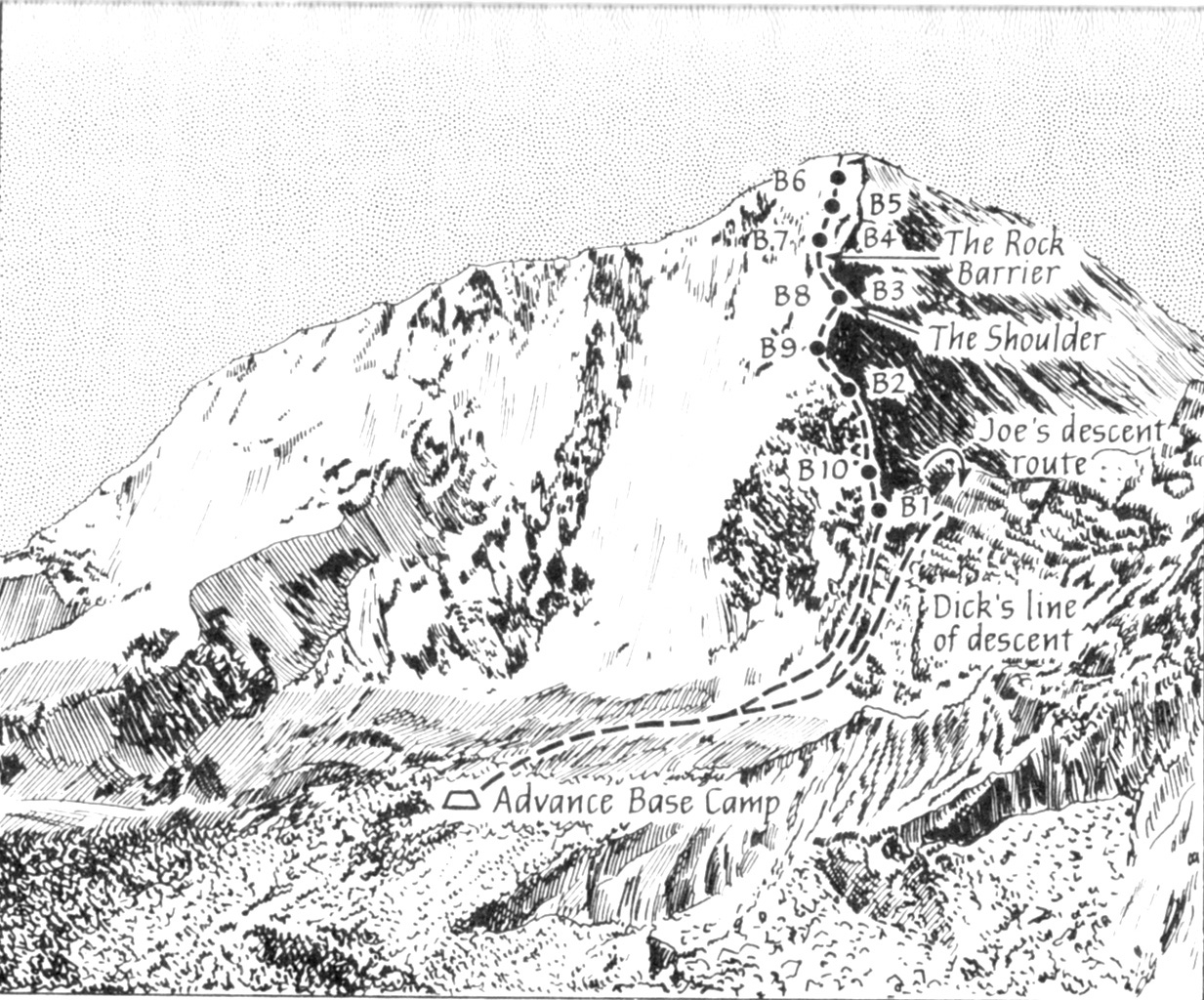

Dunagiri would be the first Himalayan climb for either of them, a pure Alpine-style attempt on a mountain that had only been climbed once before, by a route which they immediately rejected as ‘too easy’. Due to the long overland trip and the unreliable van, they arrived rather too late in the season. So without any training climbs or preliminary reconnaissance at all they set off straight up their route, carrying six days of food and – even more importantly – six days of fuel for the stove. Four days up, two down, was their simple plan. With two climbers, no preset camps, no pre-existing route to follow, it was the purest of pure Alpine style.

Given several start-up gullies above the glacier: “We chose the most difficult and most direct because we were new to this game and did not think of conserving our energies for higher up.”

At their first bivvy:

The petrol stove would not work properly; it spluttered and flared constantly, taking long hours to melt snow and heat water. We witnessed a breathtaking transformation of the milky white walls of Changabang’s granite through deepening shades of gold and orange to red as the beams of the setting sun played on that mountain, then finally lifted away to leave a colourless twilight. The night was spoilt for us by the malfunctioning stove.3

After two days of hard climbing on mixed snow and rock, and two more bivouacs, they reach the foot of a 250m wall of bare granite. Of the pair, Renshaw is the one always determined to press on. Joe Tasker is proud of himself for not now suggesting a retreat to base camp, a rest, and a return to this point with fresh supplies. Renshaw will later admit that he’s been waiting for Joe to make that suggestion in order to agree with it…

Nothing is said. They press on.

Tasker enjoys an exciting moment, in crampons, in a vertical chimney, climbing up the front of a holdless block which seems to be merely frozen in place. It’s an irreversible move, hoping for holds that can’t be seen from below. “I did not have long before my hands would uncurl their grip and I would fall.”

He climbs it, it stays stuck to the mountain, yes he is still alive. “What’s it like?” comes up from below. “O.K.” Tasker replies.

On the sixth day they reach the summit, having used up almost all their food and all of their fuel for the stove. The human body, at these altitudes, requires eight pints of water daily. Now unable to melt snow, they will be descending with no water at all. To abseil down the route they’ve just climbed will take them through exhaustion, dehydration, and weakness increasing to delirium, over five more days.

By the second day of the descent, Renshaw’s fingers are frostbitten and he is in constant pain. The weather stays kind, and the abseil anchors, fixed by mentally dysfunctional, dehydrated climbers in loose rock and poor ice, all stay in place. In a traversing move across hard, brittle ice, each of them in succession falls off, to fetch up below a single piton screwed into the ice. That piton also holds, both times.

At the final bivvy, 300m above the glacier, exhausted and half-crazed with thirst, it begins to seem as if they might survive after all. Renshaw looks across at Changabang, the even steeper and more intimidating one just the other side of the glacier. “What do you fancy doing next, Joe?”

But Tasker is promising himself a life forever close to warmth and food and liquid water, and isn’t going to put it at risk again. “I questioned myself as to whether I was more realistic and logical or whether I was inadequate and cowardly beside his undaunted determination.”

Tasker’s resolve for no more Alpine-style mountains is firm and enduring. It remains firm and enduring as he swaps the broken-down van for a bus ticket, and continues so for at least half of the long overland journey with its various dangers and discomforts.

But in his mind, and in his camera, the pictures of that even steeper, even scarier mountain just across the glacier.

Changabang.

Guided climbing up Everest is, of course, even less enjoyable – but the loads are smaller.

Notable climbs in the pure Alpine style include Joe Simpson and Simon Yates on Siula Grande, as described in the classic ‘Touching the Void’, and the ascent of Meru filmed by Jimmie Chin and Elizabeth Chai Vasarhelyi, described back in March in this post . Such ascents being even more impressive (and unwise!) when they’re on previously unclimbed routes.

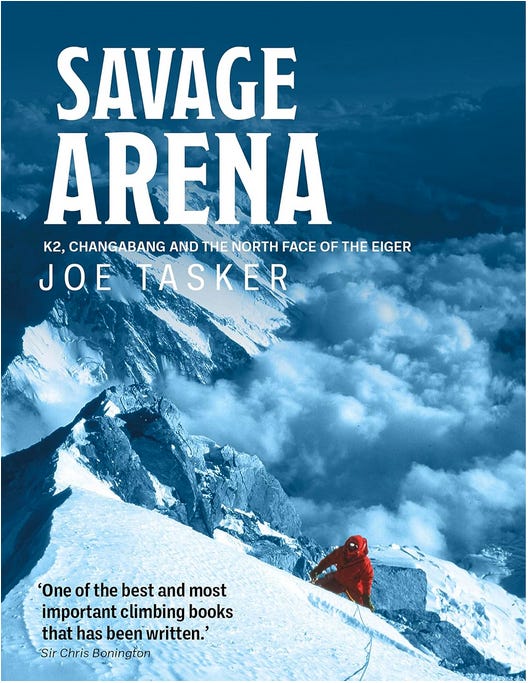

All quotes are from ‘Savage Arena’ (1982) by Joe Tasker

Thanks for your helpful article on Alpine climbing Joe Tasker I am an avid reader of Alpine climbing

epic stuff, and star lads. A special era, great times.